BY BILL DUNNE (2004)

The U.S. invasion of Iraq was a no-doubt-about-it crime of imperialism. So is the continuing U.S. military occupation of Iraq without even the fig leaf of approval by other imperial powers or their vassals and sycophants. “Shock and awe” inflicted death and destruction on the Iraqi people as well as no few working class American people and elicited revulsion and condemnation from most of the rest of the world’s people.

What prompted the minority ruling elite of the U.S. to leap into this quagmire? What motivated it to accept the huge political costs of such a risky adventure? vspace=”2″ Was it an altruistic desire to protect the world from weapons of mass destruction? Was it some noble democratic impulse to free the Iraqi people from a vicious dictator and build a shining democratic model state for people in the oppressive autocracies of the region to emulate? Was it a battle in the war on terrorism? Superficial cases have been made for these and other justifications for the U.S. seizure of a sovereign country. Or was it mere greed for Iraqi resources and labor and fat reconstruction contracts as surface events suggest? A deeper look at the circumstances indicates it was something else entirely.

Whatever the Bush regime and the U.S. elites it represents expect to get from this unilateral aggression, the political cost is clearly high. After 11 September 2001, the world had sympathy for the U.S. as the victim of an atrocity. Now, largely due to Bush and Company’s creation and handling of the Iraq crisis, the U.S. is viewed as a bellicose bully, abusing its lone superpower status to take preemptive action contrary to the wishes of its friends, allies and the world community expressed through the United Nations.

Domestically, legions of ordinary working and poor people and even elements of the middle class and traditional supporters of the Republican party are ever more loudly objecting to the waste of lives and wealth and the extent to which the repression is being brought home through more draconian national security laws. The drag on the economy of wasteful military expenditures, which destroy rather than produce wealth, is alienating millions of people adversely affected, a disaffectation that extends even to some among the ruling elite.

The result is increasing disrespect for the institutions of government and those who manipulate them. Bush and the political paradigm he represents, formerly with invulnerable ratings in the electoral charade the ruling class uses to select political leaders, can no longer be so sure of reelection next year. American interests and individuals are less secure abroad, and U.S. influence has declined. And the situation in Iraq continues to deteriorate.

The official reasons for the attack on Iraq can be dispensed with easily. There were no weapons of mass destruction. No chemical or biological weapons were used or found. Certainly, such a demonstrably brutal regime as Saddam Hussein’s would have used them when U.S. troops rolled into his country. And were that country’s borders not under intense surveillance to guard against precisely the fallback excuse that the alleged huge stockpiles of these world-threatening weapons were spirited away in the heat of battle? The secret and mobile laboratories alleged as evidence of the existence of chemical and biological toxin production turned out to be non-existent or innocuous, legitimate equipment deliberately misconstrued. And the evidence purported to prove a nuclear weapons program turned out to be a straight-up fraud. Beyond all that, the U.S. is the largest holder of weapons of mass destruction, asserts an inalienable right—yea, duty—to maintain them as a legitimate element of its “defense” policy, is the only country to have used nuclear weapons on people, and has invaded more of its neighbors than Iraq. Hence, it lacks legitimacy to take offensive action to deny others such weapons on a mere allegation of suspicion of their possession.

The notion that the U.S. and particularly under Bush the Second would sink blood and treasure into Iraq to relieve the Iraqis of their oppression and/or give hope of “democratic freedom” to people in a despotic region is laughable. History amply demonstrates that imperialists and particularly the U.S. simply do not do any such thing. Regimes installed and propped up by the U.S. such as those of Pahlavi (the shah) in Iran, Diem and Thieu in Vietnam, Mobutu in the Congo and Pinochet in Chile brought only privation and suffering to the majority of people subject to them.

Even under the neo-imperialist paradigm, exploitation and oppression are rampant as in Guatemala and El Salvador. Imperial powers have learned to exert social control via financial and political manipulation of elites who dominate economic, military and electoral machinery rather than an individual dictator, allowing them to pay lip service to democratic forms—and forms only.

Current domestic policy is another obvious indicator that benevolence toward suffering people played no role in the invasion and occupation of Iraq. Tax cuts for the rich, attacks on workers’ rights and organization, evisceration of social services such as education and health care, and environmental degradation through revised rules favoring business profits over people all characterize the Bush regime’s agenda. Hundreds of billions cascade into military adventurism, yet money for social services dries up beyond even the traditional Republican trickle-down economics. Massive deficits finance huge and bloated “security” and military expenditures that redistribute wealth and power upward and elevate interest rates and unemployment, increasing political and economic insecurity for everyone outside the ruling elite. Political machinations ensure that money and connections are the determining factors in elections, undermining the appearance of electoral democracy. The drive to create a “national security state” results in ever more exposure of U.S. residents to surveillance, searches and detention by increasingly secretive, militarized and unaccountable police agencies. With such a design for its “own” people, concluding the U.S. ruling class wants to bring freedom and democracy to anyone else is simply ludicrous.

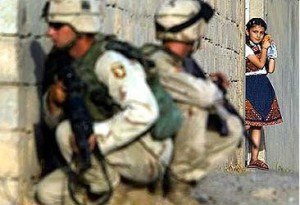

Nor does U.S. conduct in Iraq suggest much concern for weapons of mass destruction or freedom and democracy. U.S. forces raced to secure oil facilities yet failed to protect irreplaceable cultural treasures and nuclear facilities where radioactive materials were stored. They swiftly snatched well over a billion dollars in U.S. currency plus a lot of gold and other valuables, but did not look very soon or hard for the storied chemical and biological weapons. They shoot civilians who demonstrate too hard, kick in people’s doors and manhandle and detain the residents in the name of searching for weapons on the dubious word of snitches, but cannot get the water and electricity operating reliably or ensure other essential services.

Equally ludicrous is the allegation that the Iraqi regime harbored groups engaged in international terrorism or was in any way connected to Al-Qaeda or the attacks on the World Trade Center and pentagon on 11 September 2001. No such terrorists or their bases were found or incriminating documents suggesting such activity unearthed—either before or after the invasion. Further, most of the Iraqi former hierarchy is now in U.S. custody under atrocious conditions and without incentive to withhold the secrets of a dead regime. Moreover, U.S. authorities claim to have captured and to be interrogating numerous “high level” Al-Qaeda shot-callers who, to hear the authorities tell it, have been blabbing a lot about their operations. So why not about links to Iraq, if there were any? Of course, those authorities would look even more mendacious, if possible, if they tried to fly something like that without producing the source and some corroboration. And if the facts on the ground are any indication and the occupation’s own characterization of them is correct, the invasion has dramatically increased, not decreased, acts of “terrorism” against Americans.

Simple greed cannot alone explain the invasion and occupation either, though it certainly plays a role. Sure, “defense” contractors, Haliburton, Kellog, Brown and Root, Bechtel, oil interests and other economic entities well connected to the Bush regime want a cut of billions to be spent on conquest and reconstruction in Iraq. Sure, U.S. oil companies want royalties and the ability to influence markets that pumping Iraqi oil will confer. And sure, labor-intensive industries see an opportunity not only to sell a lot of stuff in Iraq, but also to gain entrée to a cheap labor market and huge new sales market in the Middle East. But those relatively few billions are only change in an 11 trillion dollar economy.

That revenue potential does provide an incentive to get influential individuals who are not architects of the policy behind the policy. And it did provide a superficial rationale for actions that might otherwise appear incomprehensible to people unpersuaded by the weapons-of-mass-destruction and other lies that avoided real investigation.

Given the economic power of the actors behind these desires for financial return and misdirection, however, such goals could be achieved by less costly means than invasion and occupation. A shadowy enemy billed as capable of striking horrifically anywhere, anytime can and did spur massive military and “security” spending. Crony capitalism provides myriad ways for the well-connected to get their snouts in the public trough—infrastructure redevelopment, as the recent blackouts might suggest, for example. Oil rights can be purchased and the costs passed on, providing yet another factor upon which to base market manipulation. And labor and market exploitation rights are also for sale, as demonstrated by the proliferation of sweat shops and penetration of consumer technology around the world.

Without the invasion and occupation, those benefits would have to be competed for and shared with other imperialist powers, particularly the European Union (EU). That competition for economic resources, especially Middle Eastern oil, is a threat to the U.S. capitalist ethos, as opposed to, say, the European. It is also a challenge to the future hegemony of the U.S. as the world’s sole superpower because the competition is not so much about the current selling price of the oil as what can be built with the economic engines it fuels. This economic warfare between the U.S. and EU elites’ versions of imperial capital reached a virtual stalemate in the 80s and 90s, leaving their inter-imperialist rivalry only to be played out by other means.

On the eve of the First Persian Gulf War under Bush the Senior, the EU was poised to make a quantum leap toward political and economic integration on a scale to rival the U.S. The collapse of the Eastern Bloc, raising of the “Iron Curtain” and fall of the wall opened a power vacuum European elites saw as an unprecedented opportunity to expand into vast new markets and sources of inexpensive labor right on European borders. Western European economies were good and buoyed by reduced need for military expenditures and the prospects of exploitation of a region with a developed infrastructure, educated population and a culturally European identity. The EU’s previous drift toward increasing its own integration accelerated and introduction of the key element of a single currency appeared imminent, apparently both motivated and facilitated by EU elites’ expansionism. Former Eastern Bloc countries were clamoring for EU aid and investment, having been sold capitalist mythology, and positioning themselves to reap it through eventual accession into the EU. The EU’s more liberal foreign and domestic policies and practices plus the circumstances lent credence to the notion that that would be sooner rather than later.

The U.S. economy, on the other hand, was relatively moribund, still suffering the ravages of Reaganomics and shortsighted investment decisions that put near-term profits above long-term industrial viability and research and development. It had smaller potential to profitably expand its political and economic sphere of influence. The booming “Asian tigers” had largely sewn up the Far East. Support for Israel limited its options and potential in the Middle East, as did its support for the apartheid regimes in Africa. Latin America was resistant to further U.S. encroachment after decades of grotesque exploitation and oppression by U.S. multinationals and U.S. support for anticommunism and rapacious dictators. These factors and U.S. direct and indirect interventions in Vietnam, Cuba, Chile, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Lebanon, Grenada and Panama gave “colossus of the north” a bad reputation in the developing world not shared by the EU.

The only thing the EU lacked—and the East Asian economies, for that matter, albeit on a longer timetable—to emerge as economic and even, eventually, military superpowers to challenge the U.S. was a secure energy supply. A determining portion of Europe and Asia’s energy needs—specifically, their oil needs—were and still are supplied by the Middle East. Other regions had oil as well, but not enough, and not accessible enough in the short term (the Middle East has about 65% of the world’s known oil reserves). Taking advantage of this Achilles’ Heel with its superior military was the only option left for the U.S. to preserve its superpower hegemony in light of its inability to secure a sufficiently sunny place via economic competition.

Circumstances suggest that the U.S. enticed Iraq into its 1990 annexation of Kuwait. The U.S. had supported Iraq in its war with Iran and otherwise, giving the Iraqi regime reason to believe the U.S. was not unsympathetic to its claims against Kuwait. Kuwait, the argument went, was violating oil production agreements and illegally tapping Iraqi oil fields and, in any event, was rightfully a province of Iraq wrongfully separated by British imperialism’s geopolitical machinations. Nor did U.S. support appear merely historical. The U.S. ambassador to Iraq prior to the invasion of Kuwait testified before congress that when Iraq queried the embassy about Iraq’s grievances with Kuwait, she was instructed to inform the Iraqis that their resolution was a bilateral matter between Iraq and Kuwait.

Saddam Hussein and Company apparently took that from the guarantor of Kuwaiti security as a green light. That the U.S. attitude expressed by its ambassador led him to conclude the U.S. might rattle the saber and make suitably shocked noises but not intervene was borne out by the fact that he could have obviated the war by the simple expedient of organizing an election. Kuwaiti “guest workers” were exploited, oppressed and disenfranchised “foreigners” with few rights who formed the substantial majority of Kuwait residents. Declaring them citizens by even a conservative tenure standard would have ensured a large vote in favor of whatever association with Iraq Saddam the Liberator proposed. Iraqi troops could have been withdrawn and the election would have been squeaky clean by any international standard. The legitimacy of a western invasion and most likely the invasion itself would have evaporated. The U.S. never went so far as to enfranchise the disenfranchised in its own conquests; Iraq thought it didn’t have to, either.

Some among the Europeans may have recognized inter-imperialist rivalry as the primary motivation for the U.S. creation of and drive to solve the problem of Iraq occupying Kuwait. But the EU was caught between a rock and a hard place. Having an acquisitive regime in Iraq in control of both Iraqi and Kuwaiti oil with a powerful military likely to be pumped up by increased oil revenues smack in the middle of the oil patch was not a good prospect for a continent with inadequate oil and no ready alternatives. Having the U.S. there under circumstances similar in relevant ways probably seemed only marginally better. World opinion was solidly against invasion and occupation of smaller neighbors and in favor of the idea of liberating a sovereign nation unjustly and brutally occupied by a regional bully. Using its powerful media apparatus and the same sort of misinformation it would later use in Gulf War II, the U.S. made it virtually impossible not to get with the coalition against a savage tyrant who would throw defenseless sick babies on the floor of a hospital so he could steal their incubators. Refusal to go along would have made the Europeans appear “soft on crime.” Plus, riding in the car and paying for the rhetorical and military gas would ensure some influence at the destination. So it would have been impolitic for the Europeans to precipitate the contradiction by voicing suspicion that the war was really against them.

The outcome of Persian Gulf War I was never in doubt. The U.S.-led, United Nations-sanctioned “coalition” of major imperialist countries, the most industrialized and wealthiest in the world with a few others thrown in for color, fell on an oil autocracy with virtually no industry that had largely squandered its wealth on its elite, repression, its war with Iran and the wrong sort of military. Iraq was evicted from Kuwait and defeated in days.

The U.S. demonstrated not only that that could not have happened without the U.S., but that it and only it dominated the oil patch. The U.S. ran the war and decided when to stop. The U.S. largely dictated the terms of he ceasefire. The U.S. maintained (under UN auspices, of course) a quasi-occupation with no-fly zones, limitations on internal activity and continuous inspections for banned weapons. The U.S. meddled in Iraq’s internal affairs, infiltrating agents, instigating and abandoning rebellions, manipulating its finances and bombing its installations. And the U.S. halted the war short of overrunning all of Iraq and deposing Saddam Hussein, undoubtedly to leave the regime a potential threat to world energy supplies the U.S. alone could handle (or not) and to avoid exactly the consequences of occupation it is reaping now.

In the wake of the First Persian Gulf War, European fortunes declined sharply. Dissention stimulated by the war undermined the impetus to integration, already strained by inadequately foreseen implementation problems. Economies deteriorated, adversely impacted both by the costs of the war and a more bearish business climate borne of insecurity in the wake of Iraq. Introduction of the euro, the European common currency, was postponed, ultimately for almost a decade. East Asian economies, most significantly Japan’s, also weakened, making them susceptible to being driven into depression and virtual collapse by speculators. The potential Asian competition for superpower status was barely emerging from shambles by the time of the Second Persian Gulf War under Bush the Junior.

On the eve of the Second Gulf War, however, the EU was again showing signs of accelerated movement toward superpower status. The western economic “boom” of the 90s allowed the economies of the EU member states to grow sufficiently to reinvigorate motion toward the desired economic integration and permit the launch of its common currency, the euro. The new elites in many Eastern European states were able to harmonize their countries to EU economic norms—despite the social costs of doing so—enough to make accession into the EU not merely a dream, but a projection. While U.S. capital also enjoyed the boom, it did not translate for it into a similar potential for economic and political expansion into new areas; its sphere of influence did not realize comparable growth.

The 90s boom also saw intense competition—warfare by other means—between the business paradigms of U.S. and European imperial capital. The dog-eat-dog, bottom line first, maximize shareholder profits above all else U.S. version had the advantage over the more socially-oriented and less predacious (at least internally) EU version. The U.S. ilk’s greater capacity for capital formation (i.e., more exploitive labor relations and stingier social contract), more pliant political establishment and a currency that had become the de facto store of wealth in the world gave U.S. business flexibility to pressure competitors and compete for control of financial and industrial resources in the global capitalist market. However, these advantages were insufficient for it to vanquish the European model and put the U.S. model and elite in the driver’s seat of the new world order of transnational capitalism.

In short, the implosion of the speculative “bubble” that had fueled the western boom led to a bust that again left military advantage the only U.S. edge in confronting the challenge to its superpower status.

Despite having mostly fended off U.S. economic aggression at home, the EU (and, verily, the rest of the world) still had no secure source of sufficient energy outside the Middle East. Perhaps it felt that UN administration of Iraqi oil and relative stability in the region made it unnecessary to shoulder the costs of developing energy independence. And perhaps competition with the U.S. on the capital fronts made it unable to do so.

The U.S. seized on the pretext of 11 September 2001 to launch a “war on terrorism,” into which car it threw Iraq, for exactly the main reason it fomented the First Persian Gulf War: to protect its sole superpower status from a European challenge. It paid lip service to building a coalition of nations to attack Iraq for laudable ends—a coalition it did not want, especially with the EU, and ends it did not really care about because they were not real.

The U.S. practice of coalition building can only be seen as intended to alienate, polarize and anger potential partners. It did so in an arrogant and unilateral way that demanded obeisance to its—and only its—right to take preemptive military action against unspecified challenges. It left room for only followers or, at best, junior partners. It presented a series of superficially attractive but ultimately false rationalizations for the aggression as rallying points. The rationalizations ensured that everyone initially reluctant would look insensitive and cowardly, that eventual recognition of the rationalizations’ falsity would occur unevenly and thus disputatiously, and that the self-serving would have a fig leaf for the other ideological and material reasons they might want to support the U.S. war. And the U.S. insisted on unseemly haste, disparaging the normal course of diplomacy.

The strategy was to inhibit the EU’s motion toward superpower status first by sowing as much suspicion, distrust, division and dissention as possible among its members and second by freezing them out of the spoils of the oil patch while holding open the possibility of individual rewards for support. Playing the liberal against the conservative elements of the European political, social and economic hierarchy was a key tactic. The U.S. induced support for the war from the conservative governments of EU members Britain, Spain and Italy, the countries into which the U.S. business model had made the greatest inroads. Ironically, it was these countries that saw the largest popular demonstrations against the war. The conservative governments in the Eastern European EU aspirants came to power largely in reaction to the failures of former, nominally communist governments and thus were ideologically disposed to such support. They were also susceptible to incentives in badly needed economic aid, coveted military assistance and leverage to ameliorate their supplicant status with the EU. Most of the rest of the world opposed the U.S. invasion, but that helped the U.S. elites’ agenda by enabling them to keep the debate at a boil both to rally “patriots” domestically and prevent the European opponents from capitulating and joining a coalition.

The strategy worked. Vitriolic disputes were engendered among European elites, both within and without the EU. The disagreement over the war rapidly grew beyond it, as news reports of name-calling, failures of cooperation and retaliation in other areas attest. The divisive issue of a future European military force was pushed to greater prominence. Expansion of the euro currency was inhibited, being set back in Britain and rejected in Sweden at least in part because its weaknesses were magnified and its strengths obscured by the war and the debate around it.

The angry wedges driven between elites of the major EU countries set integration efforts back years and perhaps a generation until the current business and political leadership is replaced. The disagreements between EU and prospective EU members stemming from the war will certainly slow the latter’s accession to the EU and their assimilation if and when admitted. In this respect, the Second Persian Gulf War worked better than the first. The very concept of the EU has been undermined, with England, Poland and perhaps other Eastern European countries at least thinking about an Atlantic identity with the U.S., Spain perhaps looking more toward a Greater Hispanic identity, and resurgent nationalism rather than regionalism or internationalism in other areas.

Moreover, the Europeans, aside from Britain—and the rest of the world, for that matter—have no significant presence in Iraq. The U.S. controls everything from agriculture to ziggurats, including the allocation of reconstruction contracts and oil sale and development rights. It recently made clear that it and not its puppet governing council retained that authority. The U.S. has also made clear that it does not intend to cede any of that control despite the billion of dollars and hundreds (thousands if the Iraqis are included) of lives that would be saved by even token concessions that would allow UN and multinational military, construction, social and economic forces to participate in the restoration of Iraq. And the oil autocracies of the region will undoubtedly be more amenable to U.S. desires and less to those of the rest of the world in the region with a military juggernaut more threatening than any Saddam Hussein could ever imagine on their borders. European interests will find it difficult to use their prior imperial and commercial connections in the region to overcome that U.S. advantage.

Whether or not the Bush regime will ultimately be forced to admit the international community and the Iraqis themselves into decision-making any time soon remains to be seen. But its aversion to doing so despite the cost of unilateralism in money and lives and even its own political viability reveals motives beyond the transparent stated objectives. The U.S. ruling class is playing a high-stakes game for incalculable wealth and power in which the scores of even hundreds of billions it is gambling are relatively meaningless. It expects to recoup the economic costs exponentially. It does not care about the suffering engendered by the absence of the social services on which that money could have been spent. It does not care about the lives of proletarians, be they children of the working class or “foreigners,” or even about the lives of a few of its own sons and daughters. And it does not even care about which hands are on the levers of government power, as long as it puts them there and they do its bidding. As quagmire Iraq shows how sticky it can be and pressure from the rest of the world mounts, dropping poll ratings for he Bush regime are just another cost of doing business. The regime is not the ruling class, merely its instrument, and thus expendable.

Successors to Bush the Second and his Imperial Court may try to slip the iron fist back into the velvet glove and the U.S. back into the global fold by saying the right words and cracking Iraq’s door. To whatever degree there may be substance behind the words, the desired damage will have been done. U.S. business, standards, finances and technology and thus U.S. dominance will already have been established in Iraq and will be in the best position to project that dominance into the rest of the region, translating also as exclusion for rivals. And it will have ensured that, barring major changes in the trajectory of world developments, the EU will not emerge as a superpower to challenge U.S. hegemony for at least a generation. Nor will any other country or group.

The foregoing is merely a superficial statement of the case for the proposition that the U.S. war against Iraq is really the new face of inter-imperialist rivalry. Military contests between imperialist powers are prohibitively costly and destructive nowadays. Proxy wars are frequently inconclusive, uncontrollable and fraught with unintended consequences. Economic competition such as that to which the former Soviet Union succumbed cannot always be carried to a definitive conclusion because competitors’ power is not significantly different, and the business cycle may intervene, depriving the contestants of the requisite weaponry. But there is still life in old-line imperialist notions of gunboat diplomacy and conquest, albeit not mainly for the old reasons of access to resources and labor. Those can generally be more readily and less riskily obtained through neo-imperialist tactics of propaganda, subversion and bribery. Control of resources and markets toward controlling competitors’ capital formation capacity by even the few percentage points around the economic tipping point mainly motivates military imperialism’s new incarnation. Presently, the U.S. is the only country that can practice it absolutely and without challenge. The history of empire, however, is that it will not always be.

From the depths of dungeon America, it is difficult to do the research required to make this case that the imperialist U.S. war on Iraq is, in fact, also a war on Europe with detailed chapter and historical verse and statistical precision. My research has been limited to the few resources available in short order from a prison cell. It has been augmented by reading and listening to the news from a variety of sources over time as well as the occasional saved article. And the analysis has been tested and refined through much discussion with knowledgeable and interested, if not academically rigorous, disputants. Hence, if the support for this point or that herein seems unduly vague or overly broad or otherwise incapable of sustaining the conclusion, investigate it.

Whatever details you might find lacking or even inaccurate (and for any you find thus, I apologize and plead the mitigating circumstances of faulty memory and limited capacity), I think you will be more convinced of the accuracy of the conclusion at the end of your investigation. And do not merely take my words for the conclusion: unless you can articulate the reasons for the positions you hold, they might have been planted by someone else—whose interests might not be compatible with yours.

Bill Dunne (10916-086)

USP Big Sandy

P.O. Box 2068

Inez, KY

USA 41224

[address updated April 2010]