I

Oh, good “Goliard”, come—come to me!

Come and listen to the sublime verses of my perverse, cursed lyre. Come and listen to the laughter of my melancholy…

What are you afraid of? What are you afraid of ?

Could you be afraid of the livid, yellow fires of my sulfurous hells?

Could you be afraid of the mysterious winds of my symbolic peaks?

Don’t you understand me?

“Couldn’t I be a false chord in the divine symphony, thanks to the consuming irony that shakes and bites me?”

But you, who are you?

Could you be some spectacled professor who still has old polemical-theoretical accounts to settle with me?

But let it go, oh Goliard, let go of ancient regrets and old torments that trouble your heart. Today is my spiritual Easter feast, my table is set…

So come—oh Goliard—to my table, drink and be quiet!

II

I am a “well of truth, black and shining, where the livid star, the ironic, hellish beacon, the torch of satanic charm, sole glory and comfort—the awareness in evil—flickers!”

But you—who are you?

“Lucky for them, the workers don’t know Baudelaire.” What did you say? Is that how it is, true Goliard? “Long live ignorance and Anarchy. Death to intellectuality, Thought and Art.” Is this what you mean, true Goliard?

But doesn’t “Goliard” signify the rebellious and dissolute student of the Middle Ages?

Ah, poor, grotesque parody!

Oh! pity… pity!

III

Certain that the good Umanitá Nova will absolve and that the Sacred Vestal Virgin—of whom you are the zealous priest—will pardon you, I—the “perverse” and “cursed” poet—invite you into my sad, melancholy oasis where unknown springs gush coolly.

Oh! Come, come!

My demon sleeps too much today and so do my pure Furies.[3]

Come, come…

I will show you the purest flowers of evil in the human garden of my heart, under the fruitful sun of my tormented soul. They are flowers of pity and sorrow, they are roses of blood and love, they are shudders and tears.

Tears of flesh and shudders of the ideal—music of urgent life, flights of spirituality…

Oh, come, come…

Today, in my hell, there is Paradise—come, oh Goliard, it is time!

IV

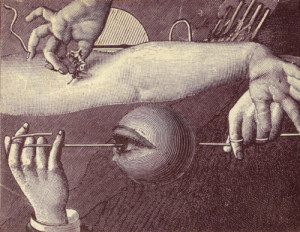

Here is the “damned Woman” whose sorrowful beauty I artistically—anarchically, humanely, sensitively—sang, whose tortured mind I raised—in song. Look at her, look at her. Do you see her, oh Goliard?

Do you hear her?

Look! There are the ones “laid on the sand, like a thoughtful herd, who turn their eyes toward the mountainous horizon,” and others are “deep in the woods stammering the loves of timid childhood.” Do you see them?

Watch, oh Goliard, as they “walk through rocks full of phantasms!” That is where Saint Anthony saw the blushing naked breasts of his temptation rise like lava…

And then there are those with “howling fevers” who call on Bacchus to drown their regrets, and others who “hide a horsewhip under their dresses” to then—in the dark forest and on solitary nights—“mix the froth of pleasure with their tears and torments.” And I—oh, Goliard of Umanitá Nova, who tried to make unconscious mockery and irony about what I wrote that you couldn’t understand—I wanted to sing of one of these “damned women”—all women are, in this sense, more or less “damned”—one of those who, like the poet, is able to say, “Skies, lacerated like seahores, my pride is reflected in you.

“Your vast clouds, in mourning, are the funeral cars of my dreams, and your glimmerings are the reflections of the Hell in which my heart revels.”

V

Charles Baudelaire, the man who—“lucky for them”—“the workers don’t know.” The marvelous poet who, without the treasury of the U.A.I. in his pocket, was able to get intoxicated with the most exquisite—even though dangerous—deep, luminous, refined sensations. The singular genius whose “mysteriously half-opened lips seemed to guard sarcastic secrets.” The strange, cursed, god-like poet who had no horror of bending down in the mud to humanely gather the Flowers of Evil and sublimate them through the tragic glow of his Art, so that he sang those “damned women” over the tremulous bow of his magical lyre.

“Oh virgins, oh demons, oh monsters, oh martyrs, great spirits, contemptuous of reality, thirsty the infinite, devotees and bacchantes, now full of howls and tears, you, who my spirit has followed into your hell, poor sisters, I love you as I sympathize with you, with your dark pain, with your unsatisfied thirst and the urns of love that fill your great hearts!”

VI

And I too—like Baudelaire—on of the great dead ones whom I secretly love—I desired—in the columns of this paper of ours—that is guilty of being called Proletario—to sing—humanely and anarchically—the tragedy, the tears, the laughter, the crying, the sorrow, the torment, the good, the evil, the sin and the hope of one of these women so that anarchists will know that, among us, not everyone is willing to throw mud and shit on those who, through an excessive thirst for the infinite, have fallen headlong into the abyss with their eyes fixed on the sky and their minds intoxicated by the stars.

And I have written this all with a pen that is my own, with a language that is my own, with a style that is original, that is my own, and that no goliardic—poorly goliardic—irony could persuade me to change by turning from my path.

VII

Some comrade—writing privately to another comrade—once characterized Renzo Novatore as “Anarchy’s Guido da Verona.”[4]

Without pausing to refute the accusation, I will say to you, as Guido da Verona had to say to his critics: “Say what you will about me, I will always give you fragrant roses… even if born in sorrow, even if germinated in tears.”

VIII

Today, my anarchist heart is full of infinite kindness. My winged mind wanders round and round through the sky of the idea.

My free spirit dances merrily in the sad oasis of my solitude—where my mysterious melancholy sings.

Come, oh Goliard—come!

Today my demon is sleeping, as are my Furies…

Come drink at the unknown, virgin springs of my infinite pity…

Tomorrow, the satanic creatures of my volcanic hell could awaken, and I could be furious…

You know? I am a strange, many-sided man.

from Proletario #3, August 15, 1922

[1] A Goliard was a wandering clerical student in medieval Europe disposed to conviviality, license, and the making of ribald and satirical Latin songs.

[2] The paper of the Italian Anarchist Federation. I believe it is still being published and has generally followed a Malatestan line

[3] A reference to the Erinyes or Furies of ancient Greek mythology, dark, primal goddesses of vengeance.

[4] Guido da Verona (1881-1939) was a poet and erotic novelist who eventually got into trouble with the fascist authorities for his writings and committed suicide to escape death at their hands.