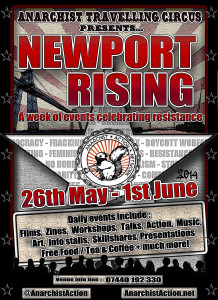

Notes for a workshop we will be giving on Friday 30 May 2014 at Newport Rising in Newport, Wales.

We don’t have the plan. We don’t think there is “a” plan. Capitalism was not made by any individual, group, party or conspiracy with a plan, and it won’t be destroyed that way either. It is far too big, complex, uncoordinated, fast-changing and unpredictable for any plan to grasp. Maybe a conspiracy with a plan can topple and take over a state, but one thing we should know by now is that taking over a state is the last thing that will destroy capitalism. It will be destroyed as the result of many acts by many individuals and groups, scattered in time and space, who may all have very different plans of their own. Though certainly some of them may confer, coordinate, copy and learn from each other.

So all we can do is make my plans, alone or with friends and comrades, for our actions, which we hope will contribute in some way to destroying capitalism. We will share a few ideas that we find useful in thinking about our plans. Perhaps they will help some others too, and spark some fruitful discussions.

1. Capitalism can only be destroyed by other cultures

If all banks, markets, capitalists, governments, policemen, and the rest of them disappeared overnight, people would recreate capitalism tomorrow. This is the story of all the ‘successful’ revolutions of the last century. We have deeply incorporated capitalist values, desires and practices right into our bodies. To destroy capitalism, we need to have other ways to live instead.

2. We need to make new cultures

An aim in every plan and action, then, is to develop and deepen, strengthen and spread new cultures that allow me, and those around me, to live freely. For us, this means: a culture in which we aim to live without dominating others or being dominated, free of hierarchy and oppression of all kinds. That is: an anarchist culture. That is what we dream of, that is what we try to live.

3. Social war

We don’t believe that an anarchist culture can coexist with capitalist cultures. We don’t believe that it is possible, today, to escape capitalism and create a utopian retreat: capitalism is an endlessly invasive culture that will leave us nowhere to hide. In any case, we won’t be free in any utopian retreat, while we know that others remain dominated and oppressed. In any case, capitalism is rapidly destroying our whole world. So if we are to make cultures that can survive and flourish, they have to be cultures that stand and fight, and can become powerful enough to destroy capitalism.

So what we are talking about is war. Social war between opposing cultures. Not democracy, ‘consensus’, or a rational public debate. Capitalist elites use ‘reason’ and democracy when they think these tactics work for them. Or they use any other means necessary, from isolation cells to cluster bombs. We’re not going to win by smiling sweetly at the cameras.

4. Create and destroy

Being at war, we need to think in two ways at once: how to create, strengthen and defend the new cultures we are making; and how to attack and destroy the capitalist structures that threaten us. We can’t have one without the other. There is no point making cultures that will be easily wiped out. There is no point just attacking capitalism without also building cultures that can flourish and take over.

So, when we make our plans, we can keep this twofold aim in mind: to strengthen and grow our cultures; to weaken and destroy the enemy.

This idea, that our struggles are at the same time creative and destructive, has always been at the heart of anarchism. We are fighting both for freedom and against domination.

5. Diversity of tactics

What kind of strategies, tactics and actions can work for this twofold aim?

Capitalist elites regularly use torture, imprisonment, indiscriminate killing, and other tactics of terror and cruelty. But using these methods wouldn’t strengthen and grow our ways of life: they would destroy and poison us, turn us into twisted copies of our enemies. Similarly, if we’re trying to get away from hierarchies, bureaucracies, bosses, leaders, elections, central committees, paid officials, market exchange, alienated labour, and all that shit, then the last thing we want to do is set up organisations that duplicate these features. To make cultures based on mutual aid and solidarity, without hierarchy and domination, we need to live these principles in our practices right now, including in attack.

Our basic criteria for thinking about strategies, tactics, plans or actions flow directly from the twofold aim.

** Will they help create and strengthen the kind of cultures we want?

** Will they be effective at weakening capitalism?

These are ‘our’ criteria, that are intrinsic to our own aims. They are the only criteria that matter. What don’t matter are ‘external’ criteria or judgements from other value systems that have nothing to do with our cultures. For example, it doesn’t matter:

** What schoolteachers, journalists, politicians, judges, cops, or other pundits and enforcers tell us is right or wrong, moral or immoral, legal or illegal.

** What the fears and social anxieties we’ve incorporated tell us is right or wrong.

** What supposed revolutionary dogmas, authorities and gurus, whether they quote Marx or Gandhi or Bakunin, tell us is right or wrong.

6. Dangerous desires

Why talk about social war between cultures, rather than just ‘class war’? We do think that the idea of class struggle can still be a powerful one. But if there’s a class war going on at the moment, it’s rather one-sided: the ruling classes beating up and murdering the exploited classes without much come back.

To destroy capitalism you need the desire to fight. Being a worker doesn’t mean you’re born with this desire, or automatically acquire it once you’re working in a factory, or a call centre or coffee shop. Working in these places makes you bored and pissed off. But capitalism has found ways to channel that anger and frustration very effectively, providing consumer dreams and desires that feed off it. In the past, workers’ movements that fought against capitalism did so because they actively made new fighting cultures, with dreams and desires all of their own.

This is one really vital point to learn from the 20th century. People’s ‘material conditions’, economic or social situations, by themselves, mean nothing for action. What count are our desires. As long as capitalism includes us within a system based on desires for consumer goods and social status, it has little to fear from us. The danger comes when the system no longer feeds those desires. This is what is happening in austerity Europe right now. Whether because elites can’t afford to any more, or because they think they don’t need to – or, we think, a mixture of both – they are pulling the post-war rug of consumerism and welfare away from millions of people. Many millions are becoming newly excluded, dispossessed.

And this is a dangerous move – as it was, for example, when early capitalism dispossessed millions of people from the land. Why is it so dangerous? Because it creates an opening for people to develop new rebel desires that can shake the system apart. But it is only an opening, a possibility. These dangerous desires don’t appear from nowhere. They need to be actively developed, nurtured, and spread.

7. Propaganda

In the past, anarchists of most persuasions were very open about their desire to spread their ideas and desires to more people. For one thing, they lived and loved anarchism with a passion, it was the ‘beautiful idea’, and they wanted to share it. For another, they knew that to have a chance of destroying capitalism they needed more comrades fighting alongside them.

So one of the most common activities of anarchists was what was called propaganda. Propaganda by word: talking about anarchism, maybe informally in the workplace or the bar, or giving speeches, talks and workshops, or ‘soap-boxing’ in the street; and producing and spreading newspapers, leaflets, images, posters, books, etc. And propaganda by deed: examples in action of ways we can live and ways we can fight.

Nowadays many anarchists, and other anti-capitalists too, seem to have gone shy. We hide and guard our ideas rather than spread them. We write and talk only for other sect-members, about boring issues no one outside the ‘scene’ could care less about. Or we use esoteric language and jargon that no one outside the ‘scene’ can follow. We treat newcomers with suspicion, or interrogate them to gauge their ‘political correctness’ before we let them in.

Spreading anarchy doesn’t mean we become politicians or Jehovah’s witnesses. We are not looking for voters, followers, cannon fodder or cash cows. We are not trying to direct or control people, but to share our thoughts and desires. Some of the people we share with may become anarchists, or at least bring bits of anarchy and anti-capitalism into aspects of their lives. Then they will also be making and spreading new cultures too, in their own individual ways.

The strength of a culture is certainly not all a matter of numbers. As an anarchist, I don’t want a mass of soldiers or followers. What I want are comrades: independent individuals who are making and fighting for anarchy in their own ways. But it would indeed be good to have more comrades.

8. Alliances

Anarchists have always been, and maybe always will be, a tiny minority. We are freaks, outsiders, with strange dreams and desires. We are not going to destroy capitalism on our own.

To destroy capitalism we need to work and fight alongside others who share some, but usually not all, of our struggles. We can make alliances that are more or less temporary or enduring, sharing particular projects and battles. If these alliances are to strengthen and grow our forms of life, they must work on the basis of mutual aid and solidarity, without domination. That means being open about our aims and intentions, not trying to lead or deceive others, but working as equal partners. We don’t aim to impose our ideas on others, but nor should we compromise our principles: if we can’t work together, we go our separate ways. (All this goes for working together with other anarchists, too.)

We think that the most powerful alliances for destroying capitalism are alliances with those who are dispossessed and excluded by the system, and have their own desires to fight.

9. Organising models

What kind of structures and practices of coordination should we use in our alliances? Here there are more important lessons from history. Mass formal organisations, like the syndicalist federations of old, have repeatedly degenerated into hierarchies and bureaucracies. The most alive and active anarchist, and other, movements of struggle today have moved well away from these models. We don’t need central committees, officials, secretaries, membership lists, elections.

This idea is one of those that can sound very strange to people who encounter anarchism for the first time, and even for many anarchists. The need for centralised order is another very powerful myth. And not just a capitalist myth, it goes back through thousands of years of hierarchical cultures. Don’t we need bosses? (Or even if we give them nice-sounding names, like recallable delegated officials.)

The best way to overcome this myth is to see it disproved in action. We’ve learnt from our own experience that we can coordinate much more quickly, securely, and powerfully as informal groups of comrades, who come together to form bigger networks and alliances when we need to for particular projects. And of course internet communication makes spread-out decentralised networking so much easier than in the past. All the most powerful actions and projects I have seen worked like this. Hierarchical decentralisation through markets is one of capitalism’s strongest powers. Non-hierarchical decentralisation, using network systems that we are still learning and developing, is one of ours.

Admittedly, what we maybe don’t know how to do – yet – is to scale up these network models to run major longer term infrastructure. For instance, if we had to coordinate a new Paris commune. Which doesn’t mean we can’t learn how.

10. Action

Ideas and desires only survive, live, develop and grow when they are put into practice. Capitalist desires are reproduced and nourished by being enacted, lived a thousand times over everyday at work, at home, in the market. In the same way, to make new ways of living means living them right now.

For example, a very important one, we can only develop fighting cultures that are able to destroy capitalism by actually carrying out attacking actions, right now. If we just dream and wait for the ‘great day’ when we rise up and make the revolution, meanwhile bowing our heads and accepting the system, we are training ourselves to be passive consumers and slaves. Only action will break our habits of passivity. Acting to attack capitalism has to be right at the heart of the cultures we are making. It plays a number of vital roles:

** It weakens the enemy culture.

** It strengthens our culture by strengthening our values and desires.

** It strengthens our culture by as we learn about what works and what doesn’t, and develop new kinds of action.

** It strengthens our culture by spreading our desires and practices: the most effective propaganda is to spread examples of how we can fight.

** It strengthens our culture by helping us form alliances: e.g., it shows potential allies that we are serious.

** It can strengthen other groups and allied cultures, as we learn from each other. E.g., if we act in ‘replicable’ ways that can be imitated and spread, and if we share information, skills and knowledge.

11. Terrains of action

Of course, in all these respects, some actions are going to be more powerful than others. There is no universal hierarchy of good and bad actions or projects: what matters is how, in a particular situation, what we do strengthens our own culture and weakens the enemy culture.

Here are just a few examples of different contexts of struggle in capitalism today:

** Classic tactics of workers’ movements have included strikes, factory sabotage, an factory takeovers or occupations. These tactics are still very present and powerful in parts of the world where industrial production remains a major part of life – for example, in regions of China where industrial action is thriving. We are not saying that they are not still relevant in countries like the UK where there is little industrial production, but they are not going to be the big front lines of struggle that they once were.

** In rural regions, and particularly highlands and other areas that are hard for states to control, rebel movements have been able to occupy and defend whole areas of territory. For example, these kinds of struggles are still going on in indigenous areas of the Americas, the Zapatista communities of Chiapas being the most famous example.

** But what about a city like London, which has no industrial production and no mountains? It’s hard not to feel like this city is about the most difficult terrain you can get, with the world’s most advanced surveillance, policing and control systems, and a pretty solid culture of apathy. But consider:

One of the key infrastructure nodes for global finance, with billions flowing through its capital markets every day. Concentrated in the centre of the city: the ‘Square Mile’ of banks and exchanges, and the hedge fund quarter of Mayfair. Heavily dependent on advanced technologies, an overloaded transport network, and compliant service workers.

The world’s biggest concentration of billionaires, oligarchs, third world tyrants and their offspring, arms dealers and warlords, and other blood-soaked bastards.

Thousands of refugees and exiles, often from war zones destroyed and depopulated by said bastards, many with their own strong traditions of struggle.

Surrounding the moneyed quarters, a population increasingly unemployed, excluded, dispossessed, gentrified, evicted, sanctioned, raided, beaten, tasered, and otherwise fucked over. After 2011, the lid stuck down with ‘total policing’ and 1000 prisoners, but for how long?

In some ways, London is a paradigm of many global cities. Not factory cities, but new mercantile hubs of financial power and money-laundering for ‘super-rich’ world elites. These cities are key nodes for global flows of wealth and power. Like mercantile cities of the ancient and medieval past, their vulnerability and fear is not industrial action but urban unrest, the ‘mob’.

These are just three examples of different terrains of struggle. Individuals and groups active in these zones might follow very different strategies and tactics, and develop quite different organising structures. But perhaps they can also learn a lot from, and inspire, each other.

And also: imagine what kinds of links and alliances revolutionaries could form between these different zones. For example, rural ‘free territories’ sometimes link up with and act as bases and zones of retreat and education for industrial and urban movements. (And the very existence of ‘free territories’ has a great symbolic and inspiring power.) Or what if workers in the ‘developing’ world find ways to coordinate actions with people in the global cities where their products are financed and the profits laundered?

12. Infrastructure

Effective action requires infrastructure and resources. To grow strong cultures we need:

** Spaces to meet, learn, think, plan, welcome new people. Historically many kinds of spaces have played these roles: cafes and pubs, meeting halls, free schools, social and cultural centres, festivals, fairs, camps, picnics (a big tradition of Spanish anarchism), hiking clubs, …

** Spaces to live, sleep, hide, recover.

** Resources for production and spread of information: printing presses, publishers, computers, servers, distribution networks, libraries, study groups, …

** Resources for action of all kinds.

** Transport infrastructure: e.g., vehicles, garages and repair workshops, cross-country and cross-border accommodation and travel networks.

** Communications infrastructure and secure networks.

** Means to live: food and drink and all the basics we need to survive and keep healthy and well.

** Health: access to doctors and medics, medical supplies and equipment, all resources to care for our bodily and mental health.

** Education, training, sharing of skills, knowledge and arts of all kinds, for struggle and for life.

** Music, art, dance, spaces for social life and community, places to get lost in nature, all things that bring us joy and keep us strong without dominating or exploiting others.

Well resourced movements are vital for action. To give a very basic example, in a city like London we have an everyday struggle just to survive. To pay rent and bills. Or spend much of our time just on finding, maintaining and defending precarious cold squats. To bring together friends and comrades scattered across the city. To make spaces that are welcoming for people outside our existing ‘scenes’. To find peace and beauty to replenish energy and soul in a desolate urban landscape. We can end up becoming burnt-out city drones, or we just abandon the field – thus a transient turnover of comrades who don’t stay for long or make commitments.

What if we could have a culture with the spaces and resources to feed, nourish, house, equip, teach, support and inspire each other? Just developing some of this basic infrastructure could dramatically strengthen our movements in the city.

Again, there is no universal hierarchy of means that are best for doing this. The same criteria apply for actions and practices we use, for example, to find food, equipment and shelter. Do these practices strengthen the culture we are making? Do they empower us to attack?

Again, it is only ‘our’ criteria that matter. Not how a means is judged by external standards of the dominant culture. For example, whether it is legal or illegal.

For example, many anarchists have found using illegal means to fund themselves both very effective, and a powerful part of creating cultures that challenge authority, obedience, and submission. Others create cooperative structures for housing, employment, transport, etc. But we shouldn’t treat illegalism or cooperative structures as dogmas. In many situations it can be more empowering overall to stably own or rent a building, open a cafe that sells food, or do paid work.

In thinking about these questions, we can also look to what potential our practices have for future development. For example, as capitalism hits increasing economic and ecological crises it could get harder to live off work, welfare or plunder in big cities. It might make sense to become increasingly self-reliant, and get in place the skills and structures to do this. We could start developing these now.

13. Acts of creation and destruction

To sum up, here are a few things we can think about in terms of making, strengthening, and growing our cultures:

** Building infrastructure and resource chains, which create means and spaces for our cultures to flourish.

** Learning and training new skills, practices and structures.

** Studying, thinking, alone and together, experimenting with new ideas.

** Propaganda: sharing desires and practices with others, particularly those being dispossessed by capitalist culture.

** Making alliances: finding and getting to know other rebel groups and individuals.

The cultures we make need to be fighting cultures, which do not hesitate to attack and undermine capitalism. Acts of attack may involve, to note some very broad points:

** Attacking capitalist infrastructure and resource chains, means and spaces.

** Constantly outwitting, pre-empting and overcoming enemy tactics and attacks.

** Studying, examining and overcoming capitalist values, desires and practices in our own lives too.

** Negative propaganda: undermining capitalist values and desires, e.g., by exposing myths and lies, or by demoralising elites.

** Undermining capitalist alliances: helping divide elites and their allies and accomplices.

14. Dare

It’s good to make plans and think strategically about what we’re doing. But above all, it’s good to act. And the most powerful and surprising outcomes often come completely unexpectedly. Experiment, take risks, try new things, dare. If you don’t, what kind of a life do you have to lose?

“Our hope was folly, but then revolutionists have their heads a little out of… equilibrium. And without this folly the world would never change, and revolutions would perhaps be impossible.”

Enrico Arrigoni, Freedom: My Dream.

…

Some influences and further reading

Where do the ideas in this chapter come from? Where do any ideas come from. A load of sources, some you can consciously identify, others you’ve unconsciously incorporated, and all of them digested and mixed up in your own ways.

NB: pretty much all these texts can be found at theanarchistlibrary.org

Positive and negative

The idea that our projects are both creative and destructive, building and attacking, struggling at once forfreedom and against domination, has always been at the heart of anarchism.

Bakunin made this point with his famous phrase ‘the passion for destruction is also a creative passion’ in 1842 – albeit in a rather abstract article laced with Hegelian philosophy of ‘the spirit’ (called The Reaction in Germany), and before he had actually become a revolutionary anarchist. The line immediately before is: ‘Let us therefore trust the eternal Spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unfathomable and eternal source of all life.’ Destruction isn’t a end in itself, but necessary for new life.

The same point was made again and again by many ‘classical’ anarchists. For example, Emma Goldmanin ‘Anarchism: What it really stands for‘ addresses two big criticisms of anarchism: it can never work; it’s just mindless violence and destruction. Her argument is very close to Bakunin’s, and also uses a grand metaphor – ‘nature’ rather than Hegelian ‘Spirit’:

‘Destruction and violence! How is the ordinary man to know that the most violent element in society is ignorance; that its power of destruction is the very thing Anarchism is combating? Nor is he aware that Anarchism, whose roots, as it were, are part of nature’s forces, destroys, not healthful tissue, but parasitic growths that feed on the life’s essence of society. It is merely clearing the soil from weeds and sagebrush, that it may eventually bear healthy fruit.’

But this doesn’t mean focusing on negative destruction now, so we can have happy creativity in the future. Anarchism (usually) rejects this idea of deferred life. We want joy today, even as we’re in the midst of the war. Here’s how Kropotkin, for example, makes this point (in his ‘Anarchist Morality‘):

‘Struggle! To struggle is to live, and the fiercer the struggle the more intense the life. Then youwill have lived, and a few hours of such life are worth years spent vegetating. Struggle so thatall may live this rich, overflowing life. And be sure that in this struggle you will find a joy greater than anything else can give!’

This attitude is at the heart of so many anarchist writings from before the Second World War. To see how anarchist lived it in action – and also thought about strategies for destroying capitalism, too – perhaps the best references are not theoretical texts but memoirs and letters. Just to name a few examples: Kropotkin’sMemoirs of a Revolutionist; Goldman’s Living My Life; the Prison Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti; or Enrico Arrignoni‘s autobiography Freedom: My Dream, quoted at the end of this chapter.

We seem to have lost sight of these points sometimes in recent anarchist writing. A very big problem here was that, as anarchist movements weakened after the 1930s, they became vulnerable to the spread of defeatist pacifism. See Peter Gelderloos – How Nonviolence Protects the State for an analysis of the ‘dogma of nonviolence’, how it has helped make anarchist and other anti-capitalist movements (at least in rich countries like the US) increasingly passive and submissive in recent decades, and so served well the state and capital.

In the 21st century some currents of insurrectionalist anarchism have swung right the other way, towards an attitude very largely focused on destruction. At least in part this seems to be a reaction to the passivity of previous generations of anarchists, anti-capitalists – and people in general under capitalism today. A destruction-focused view of anarchy is sometimes associated with the idea of nihilism. For a useful introduction to nihilist thinking, and its historical and current relationship with anarchism, see Aragorn! – Nihilism, Anarchy and the 21st Century.

The dispossessed, and informal organisation

Alfredo Bonanno’s From Riot to Insurrection, from 1985, develops the idea of struggles of the ‘included’ and ‘excluded’ in contemporary capitalism. He looks at the growing gulf between those still ‘inside’ the ‘castles’ of capitalist consumption, work and welfare, and the dispossessed pushed out into the cold.

Wolfi Landstreicher is another insurrectionalist writer, influenced by Bonanno, who looks at class struggle in terms of ‘dispossession’ in The Network of Domination. He argues that ‘The ruling class is defined in terms of its own project of accumulating power and wealth.’ While ‘The exploited class has no such positive project to define it. Rather it is defined in terms of what is done to it, what is taken away from it. Being uprooted from the ways of life that they had known and created with their peers, the only community that is left to the people who make up this heterogeneous class is that provided by capital and the state …’

These two texts are examples that’s pretty rare: serious anarchist analysis of capitalism, how it is changing and so how our forms of struggle need to change too. They try to think beyond Marxist approaches which have been too much of an intellectual straitjacket, often on anarchists too. Although to some degree, as in that quote from Landstreicher, in some ways they still stay rather close to Marxist thinking.

Bonanno’s essay From Riot to Insurrection, and other writings, then goes on to argue strongly that only ‘informal’ organisation can destroy capitalism in its new forms :

‘If industrial conditions of production made the syndicalist struggle reasonable, as it did the marxist methods and those of the libertarian organisations of synthesis, today, in a post-industrial perspective, in a reality that has changed profoundly, the only possible strategy for anarchists is an informal one. By this we mean groups of comrades who come together with precise objectives, on the basis of affinity, and contribute to creating mass structures which set themselves intermediate aims, while constructing the minimal conditions for transforming situations of simple riot into those of insurrection.‘

‘From Riot to Insurrection’ was written in 1985. Though its core points are spot on, understandably some of its predictions now look rather off-target. To help bring the analysis of shifting ‘inclusion’ and ‘dispossession’ into the 21st century, again, Desert (by Anonymous) is a good starting point. It adds two important elements: the role that ecological crises are playing and will play; and how these shifts are developing very differently in different global regions.

Propaganda

For one old-school anarchist approach to propaganda see Errico Malatesta – Anarchist Propaganda. Malatesta thinks that:

‘Our task is that of “pushing” the people to demand and to seize all the freedom they can and to make themselves responsible for providing their own needs without waiting for orders from any kind of authority. Our task is that of demonstrating the uselessness and harmfulness of government, provoking and encouraging by propaganda and action, all kinds of individual and collective initiatives.’

Malatesta also argues that ‘as a general rule we prefer always to act publicly’. Of course there are situations when we need to act secretly and clandestinely:

‘One must, however, always aim to act in the full light of day, and struggle to win our freedoms, bearing in mind that the best way to obtain a freedom is that of taking it, facing necessary risks; whereas very often a freedom is lost, through one’s own fault, either through not exercising it or using it timidly, giving the impression that one has not the right to be doing what one is doing.’

As for more recent efforts, looking at it from the UK, there is one beacon that still shines: the newspaperClass War. The best recent example, at least in English, of how to get across uncompromising anarchist and class struggle messages to a wide audience. Though not all that recent: we haven’t had much like this since the 1980s! See the book by Class War founder Ian Bone – Bash The Rich for more about the paper and the times.

Class War also shows that writing in an accessible style doesn’t mean you can’t do serious analysis and strategy too. A great example of this is Martin Wright‘s 1984 Class War article Open The Second Front. This is another rare thing: strategic thinking in the heat of the action, precise, direct, clearly written, and incendiary.

Diversity of tactics

Leaving aside the idea of ‘the masses’, here is a resounding statement of much the same kind of point we’re trying to make, from the UK ‘libertarian socialist’ group ‘Solidarity‘ in their statement ‘As We See It’ of 1967:

‘Meaningful action, for revolutionaries, is whatever increases the confidence, the autonomy, the initiative, the participation, the solidarity, the equalitarian tendencies and the self-activity of the masses and whatever assists in their demystification. Sterile and harmful action is whatever reinforces the passivity of the masses, their apathy, their cynicism, their differentiation through hierarchy, their alienation, their reliance on others to do things for them and the degree to which they can therefore be manipulated by others – even by those allegedly acting on their behalf.’

One of the main ‘dogmas’ that can cause problems in thinking about types of action is the pacifist dogma of non-violence. To be clear: the point is not that ‘violent actions are always good’. That would just set up a new dogma in reverse. Once again, ‘good’ actions are those that empower and strengthen our struggle. Sometimes, these actions will involve the use of force. It should never fail to be pointed out that we face the much greater violence of the state, a murderous war machine. On these points see Peter Gelderloos: How Non-Violence Protects The State.

On issues of ‘legalism’ or ‘illegalism’, a text from 1911, Is The Illegalist Anarchist Our Comrade? by the individualist anarchist Emil Armand, that still makes strong points. It concludes:

‘the criterion for camaraderie doesn’t reside in the fact that one is an office worker, factory worker, functionary, newspaper seller, smuggler or thief, it resides in this, that legal or illegal, MY comrade will in the first place seek to sculpt his own individuality, to spread anti-authoritarian ideas wherever he can, and finally, by rendering life among those who share his ideas as agreeable as possible, will reduce useless and avoidable suffering to as negligible a quantity as possible.’

To life

Enrico Arrigoni, who’s quoted at the end, was a wandering individualist anarchist who had an amazingly rich, joyful and active life, full of travels, love affairs, friendships, learning different trades, and participating in a dizzying number of revolutions. Again, a lot of the best ideas and examples for struggle are not to be found in theoretical tracts but in memories like his.