Either as a political issue or personal experience prison repression isn’t something the radical left in Britain is particularly familiar with or much inclined to mobilise against. Prison remains largely a working class experience targeted against the poorest and most marginalised of that class. However in a society increasingly polarised and divided between rich and poor in a political climate of growing repression and authoritarianism prisons are being refashioned more and more into instruments of political as well as social control. This will eventually find reflection in the nature and composition of the prisoner population as political activists increasingly supplement the imprisoned poor.

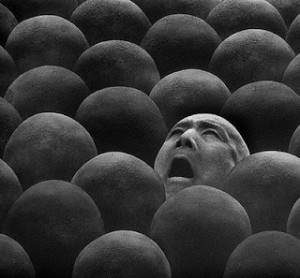

What should characterise the behaviour and attitude of imprisoned political activists towards the prison system? How should those imprisoned for political offences against the system in the “free world” behave and respond once incarcerated in the Belly of the Beast, the steel and concrete innards of the state?

In Britain imprisoned political activists tend to view their time behind bars as a period of uneventful neutrality, as a passive killing of time before returning to the “real” struggle beyond the walls and fences that temporarily enclose them. Of course in places like Northern Ireland where conflict and repression was woven into the fabric of people’s lives prisons were not just a commonly experienced reality but also important political battle grounds in the struggle for freedom and liberation. For Irish Republican prisoners their confinement within the notorious H Blocks did not mean the termination of their struggle for Irish national liberation but rather an intensification of that struggle to the extent where their lives were sometimes sacrificed through hunger strikes. Like imprisoned revolutionaries in fascist states throughout the world Irish Republican prisoners responded to prison repression just as they had responded to repression in the broader society, by resisting and fighting back. They believed it their political duty as revolutionaries to respond to repression with political integrity and defiance, no matter what the inevitable personal consequences.

In Britain, however, most of those imprisoned for political offences, including “terrorist” activity, tend to conform to prison life and acquiesce to the authority of those enforcing their imprisonment. The spread of what the government and media have described as “Islamic radicalisation” within British prisons has not been accompanied by a serious destabilisation of prison regimes or increased collective unrest within prisons; on the contrary, solidarity and collective resistance amongst prisoners has significantly diminished over the last 10 to 15 years, suggesting almost an inverse relationship between the alleged “radicalisation” of prisoners and their propensity and inclination to collectively resist and fight back. Whilst it is undoubtedly true that the spread of Islamic beliefs amongst young black prisoners, in particular, has been considerable over the last decade it would seem that this “radicalisation” has been more of a personally transformative experience than a collective commitment to organising and resisting prison repression, unlike, for example, in U.S. prisons during the 1960s and 70s when Nation of Islam or Black Muslim prisoners organised and fought back against the prison system. Significantly, a hero and source of inspiration for prominent black power prisoners in the U.S. during the 1960s was Sergey Nechayev, a 19th century Russian anarchist and author of “Catechism of a Revolutionary”, who believed that once politically conscious the revolutionary had an absolute duty to commit and if necessary sacrifice ones entire life to the struggle. Nechayev, imprisoned by the Russian tsarist regime for “terrorist activities”, would eventually die chained to the wall of his cell in the notorious fortress of St Peter and Paul in Moscow.

In a more modern context possibly social class itself is a significant determinate in how those imprisoned for political activity respond to that imprisonment. IRA prisoners and militant black prisoners in the U.S. were generally from poor working class origins and places where police harassment and brutality was a common experience, alongside an intimate knowledge of places of incarceration, often from an early age. In prison such activists naturally bonded with ordinary working class “offenders” and shared with them a common life experience of poverty and repression; prison was simply another front of struggle as far as these imprisoned revolutionaries were concerned. For the political activist from, say, a more middle-class social background prison is much more a completely alien experience and a place largely populated by those from the other side of the track and with whom they share absolutely no personal or cultural affinity or experience whatsoever. The relationship of the imprisoned usually white middle-class activists with those who wield absolute power in jails, the guards and senior managers, also tends to be significantly different from how most working class prisoners relate to those enforcing their imprisonment. In prison to resist and fight back inevitably is to invite even greater repression and pain, and yet amongst many working class prisoners there exists an almost instinctive propensity to fight and challenge the absolute authority of their jailers. On the other hand, for those originally radicalised by revolutionary theory, as opposed to personal experience, and thrust suddenly into an enclosed world of sharp edged repression where the power of those enforcing it seems unassailable and resistance to it pointless, the priority becomes one of adjusting to the prevailing reality and doing whatever is required to get oneself through the experience as quickly and painlessly as possible before returning to the real struggle outside. It obviously makes no tactical common sense to confront a manifestation of institutionalised state violence from a position and condition of total disempowerment. From such a perspective prison is not a place of struggle but simply a place to quietly sit out one’s time and put on the psychological blinkers. Some not accustomed to the reality of prison are badly traumatised by it and the first real experience of naked repression; an academic understanding and knowledge of repression is no preparation for a direct personal experience of it. For the “lumpen-proletariat” however and the politically conscious of them, prison repression is a familiar experience and like oppressed people everywhere their response to it is characterised by resilience and fortitude.

Beyond the walls of the micro-fascist society of prison the illusion of “freedom and democracy” is being increasingly replaced with the reality of a class divided society no longer mediated by consensual rights and liberties – authoritarianism and coercion are the weapons increasingly used to maintain order. In such a political climate more and more activists and libertarians will experience and suffer imprisonment, and more will have to learn that prison is simply another front in their struggle.

John Bowden – September 2015

HMP Barlinnie