On Saturday June 2, 1978, a group of nine people gathered in a room of the Southern Cross Hotel in the Melbourne CBD to launch the National Front of Australia (NFA). According to the ASIO informant, nine people attended the meeting, including several well-known far right activists, a 16 year old schoolboy and an undercover reporter for the newspaper The Age. Seven out of the nine listed were already known to the authorities in some regard. The meeting was led by a 23 year old law student and army reservist, Rosemary Sisson, who had travelled to the UK in 1977 to seek permission from the National Front’s John Tyndall to establish an NF in Australia. According to ASIO, Tyndall had appointed Sisson to be Chairwoman of the NFA until a directing body was created. In a report on Sisson by the Victorian Police’s Special Branch, Sisson was described in these terms:

She appears to be intensely sincere in her beliefs but politically naïve and immature. I do not believe that she has the ability to form a political party on her own volition and would most likely be used by other persons taking advantage of her enthusiasm, while maintaining their anonymity.

The meeting, which lasted between two and four hours, commenced with the playing of God Save the Queen and passed several motions relating to the outlook of the NFA, the composition of the National Directorate, membership fees and a statement of ambition regarding the contesting of elections in the near future. The ‘highlight’ of the meeting was listening to a tape recording of Tyndall. The ASIO informant described Tyndall’s speech as such:

Tyndal’s [sic] speech included greetings to the newly formed NFA and congratulations and it is encouraging to him that the National Front had extended to Australia… He pointed out that the National Front had been established for almost 12 year and during this time there had been clashes with the authorities, Police Special Branch and most left-wing groups. In spite of all this, they had conducted massive demonstrations and never instigated violence but violence was forced upon them… The speech continued with the usual self praises and self congratulations for the National Front.

Tyndall also mentioned in his speech that National Fronts had been established in several other countries, such as New Zealand, Canada, South Africa and Rhodesia. After Tyndall’s speech, a letter of congratulations from the leader of the New Zealand National Front, David Crawford, was read out. Sisson saw the connection to the British NF as very important and most of the policies outlined at the meeting centred around maintaining Australia’s links with Britain, the Commonwealth and the ‘Anglo-Celtic’ race. These included the establishment of the Commonwealth National Front (CNF) as a (theoretical) co-ordinating body of the various NFs across the globe and the call for the reconfigurement of the British Commonwealth as ‘an exclusive closely-knit association of White states’, where there was either a large white population or ruling white elite. This led to the calling for the re-entry of Rhodesia and South Africa into the Commonwealth and support for white rule in both countries. As evidenced by the singing of the old national anthem, loyalty to the British Crown was paramount to the NFA.

The Age journalist that attended the meeting was David Wilson who wrote about the establishment of the NFA in the newspaper the following week. Wilson described the secret meeting of nine people as:

the culmination of 12 months’ work: trips by England by two of the nine, talks with the head of the English movement, Mr John Tyndall, letters to the chairman of the New Zealand division, Mr David Crawford, and weeks of long hours carefully selecting the initial members of the Australian movement, printing, letter writing and telephone calls.

According to ASIO intelligence reports, a Birmingham based NF organiser, Jeremy May (who had previously lived in Australia), had travelled in early 1978 to assist Sisson in setting up the NFA, while Sisson also communicated with Tyndall in writing. In an intercepted letter between Sisson and Tyndall, written in late November 1977, she concurred that the NFA would supposedly operate differently than the British NF, writing:

We agree with your suggestion that an Australian NF body should aim to function – at least initially – as a pressure group concentrating on basic political technique and party organisation, rather than attempting to achieve mass popular appeal and publicity.

This letter was written in the wake of the ‘Battle of Lewisham’ in August 1977 when the British NF attempted to march through a borough of south-east London with a large African-Caribbean community. The clashes between anti-fascist protestors and the police, as well as with some NF members, brought the NF to attention of many Australians as the scenes were broadcast on the news. The NF had shifted in their strategy from attempting to gain influence amongst ex-Conservative Party voters and building its membership base to a strategy of ‘owning the streets’ and gaining as much as publicity as possible from these street battles, whilst simultaneously contesting elections and trying to siphon off disaffected Labour voters. It seemed from Sisson’s letter that the NFA were not expecting to mimic the British NF’s approach just yet – with only a handful of interested people, occupying the streets was too tall an order for them.

(The ‘Battle of Lewisham’, August 1977)

The month before the establishment of the NFA, May wrote an article in Tyndall’s journal (aligned to the NF at the point in time) Spearhead, titled ‘Towards a National Front of Australia’. Like Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in the 1930s, the NF saw Australia as ‘a vast and fascinating country with tremendous social and economic potential’ and while the country was ‘almost completely self-sufficient in economic resources’, it was perceived that Australia was at the mercy of foreign investment and international liberalism. May pointed to the ending of the ‘White Australia Policy’ as a particular symbol of Australia’s despair, lamenting the ‘invading hordes’ from southern Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Furthermore, May focused on Australia’s ‘complete absence of protection for almost the entire length of the country’s vast coastline’ as another example of the country’s weakness, with the naval defences, described as a ‘bathtub floatilla’, unable to prevent ‘Chinese drug racketeers, Pacific Islanders and, most recently, Vietnamese refugees’ from reaching its shores. Despite this, Australia was still seen as a bastion of the old white Commonwealth at a time when South Africa and Rhodesia seemed on the verge of collapse. May warned Spearhead’s readers:

Let us be clear on one point. Should South Africa ever fall to the forces which threaten to engulf Western civilisation, we can be sure that Australia will be next on the list. Liberalism is a luxury which Australia simply cannot afford, if only for geographical reasons. No protection money will ever be sufficient to dissuade the teeming Asiatic billions from erupting into the island continent once they get their chance.

May declared that the only way to ‘safeguard the nation from this fate’ was the creation of the NFA, which he described as ‘an urgent and imperative necessity’. ‘Native Australians’, by which May meant white Australians with an Anglo background, ‘are a proud, strong-minded and independent people’, who also maintained their links to British. And it was up to the NFA to ‘ensure that this distinctive national identity… is encouraged, enforced and politically activated.’

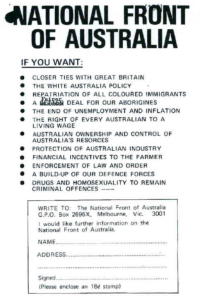

With this mission in mind, the establishment of the NFA was preceded attempts to gauge public opinion through the secret distribution of literature across Melbourne. As David Wilson wrote in The Age, ‘The only indication of the secret spread of the movement was through the carefully circulated newsletter, The Australian Nationalist.’

The Australian Nationalist had started appearing from January 1978 and was a mimeographed publication written by Sisson. The first issue called for a united Australian nationalist party and bemoaned that the nationalist movement at that time was ‘almost hopelessly and irretrievably fragmented into mutually suspicious, competitive, and absurdly idiosyncratic, exclusive little groups.’ But Sisson declared:

IT IS IMPERATIVE THAT WE REGROUP AND UNITE! Only though unity and the strength this gives us can we begin to tap and realise the incalculable political potential of national patriotism within this country.

Sisson pointed the British NF as the example ‘forever before our eyes’ of the unification of several different far right groups (in 1967, the NF had formed from the remnants of the League of Empire Loyalists, the British National Party, the National Democratic Party, the Greater Britain Movement and the Racial Preservation Society). The Australian Nationalist expressed a pro-British Commonwealth nationalism and its influences were very much drawn from the British fascist movement, rather than the American far right. Similar to May’s article, Australia was portrayed as the bastion of the white British civilisation on the periphery of Asia and Sisson argued that this meant that a strong nationalist movement was needed to maintain this position. The fear of invasion by Asians was long-standing in Australia and Sisson evoked this in a January 1978 article:

The geographical situation of Australia, with its close proximity to some of the most populous of Asiatic nations, impels us to be very much on our guard against nationally destructive propaganda…

In the editorial to the April 1978 edition of the newsletter, Sisson further championed Australia’s links to Britain and the importance of their ‘proper ethnic pride’. She argued:

Australia owes almost everything it has to Great Britain. The conquering and pioneering spirit of our forefathers was British. This can never be denied. If anything, we should seek closer links not only with white Europe, but to a greater extent with our mother country. Even though we are no longer a cluster of colonies, but are fully self-governing and independent, there is no reason why we should forsake our history and clamour for a republic.

In June 1978, The Australian Nationalist became Frontline: Magazine of the National Fronts of Australia and New Zealand, with the debut issue dedicated to the formation of the NFA. Unlike the descriptions by ASIO and by David Wilson in The Age, the June meeting of the nine people to form the NFA was described in Frontline in grandiose terms. Quoting the opening address by Sisson, meeting supposed ‘mark[ed] an important event in the political history of Australia’ by forming a new political party that ‘represents the future of the Australian people’ and ‘revive national pride’. The magazine also carried the text of Tyndall’s speech heard at the meeting, in which Tyndall described Australia as a terra nullius transformed by British settlers into a bulwark of white civilisation on the edges of the British Empire:

Australia was not so very long ago a wilderness inhabited by a few savages, and it took some very hardy determined, self-reliant and tough pioneers to carve a great country and a great civilization out of that wilderness…

Tyndall enthused about the formation of the Commonwealth National Front, remarking that the ‘realisation of the National Front spanning the whole British Commonwealth has always been a dream to me’ and with the establishment of the NFA, ‘the sight of this dream being fulfilled is enormous encouragement to me’. Tyndall asserted that the NFA was not subordinate to the British NF and there was to be ‘equal partnerships’ between the NF in the UK and those in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In an article in Frontline, the CNF was to co-ordinate activities amongst the various NFs across the Commonwealth, but allowed discretion to each NF to function as it desired. The article explained:

Subject to their adherence to a common set of basic principles and objectives, National Front organisations in various countries are free to determine their own rules of association, to make their own executive decisions and to determine themselves all policies relating to their own countries’ domestic political affairs.

The above will include the right to determine whether the National Front in a particular country will function as a fully fledged political party, seeking power in its own right by the ballot box, or whether it will function merely as a pressure group or society for the furtherance of National Front ideals.

The magazine also carried the letter of congratulations from the NFNZ’s leader David Crawford, which described the NF as ‘the vanguard of the most impelling force ever to strike your country in the last 100 years’. Crawford mentioned that National Fronts now existed in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada. The journal Patterns of Prejudice noted the announcement of the Commonwealth National Front in mid-1978, but stated that the only NF that had been set up by that time was in New Zealand – although by March, 1979, ASIO believed that the NFNZ was ‘almost finished’. Patterns of Prejudice that NFs in Canada and South Africa were still in development.

The 16 year old schoolboy that attended the inaugural meeting of the NFA was David Greason. In his autobiography, I was a Teenage Fascist, Greason described the meeting as a ramshackle and ill-organised affair, with him moving a motion for the formation of the NFA, even though he had not seen the motion previously. Greason described that in the days following the meeting and the publicity given to the NFA in the mainstream media, several different far right identities, usually linked to the now defunct national Socialist Party of Australia claimed to part of the NFA’s leadership. This is borne out in the ASIO files, which catalogue that various people in Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales all claimed to represent the National Front in Australia. According to Greason and ASIO, the NFA seemed to be limited to Victoria and Queensland, where the Queensland Immigration Control Association (run by John C.A. Dique) had significant influence. The rival to the NFA in Sydney was the National Alliance, which eschewed the pro-Britishness of the National Front and leaned more towards the white supremacism coming out of the United States, influenced by the infamous newspaper National Vanguard. According to Greason, National Alliance tried to foster a uniquely Australian nationalism, appropriating the symbolism of the Eureka Flag and promoted the idea of an Australian republic. The leading figure of the National Alliance was Jim Saleam, who had been a member of the NSPA and went onto form groups such as National Action and the Australia First Party.

By mid-1979, Patterns of Prejudice was reporting that the NFA had between 100 and 300 members, but had been subject to in-fighting, particularly as Sisson made trips to the UK to meet with Alan Birtley, a NF member jailed for weapons and explosives offences. The ASIO file carries significant correspondence between Sisson and a NF member named Margaret Swan, whom Sisson discusses her links to Birtley extensively.

In the UK general election in May 1979, the British NF contested more than 300 seats and were wiped out at the polls, receiving barely more than 1 per cent of the vote on average. Similar electoral contests by the NFA in 1979 and 1980 led to the same results. Greason outlines that by 1980, there had been several defections from the NFA to the National Alliance, but the National Alliance was unable to make any more headway than their rivals. The media also focused less on the National Alliance, which did not have the same name recognition of the ‘National Front’, which was infamous across the English-speaking world.

The Commonwealth National Front did not last long into the 1980s. The NFA emerged to a completely hostile media and fared very poorly in its electoral pursuits, but was also not popular enough to take up the strategy of ‘occupying the streets’. Besides the production of Frontline, Sisson’s organisation dwindled and eventually over taken by rival groups, namely National Action. Patterns of Prejudice also reported in 1978 that the National Front of South Africa was in talks of merging with another small racist group and that the Chairman, Jack Noble, had resigned. The NFSA’s other major figure, Ray Hill, also left South Africa in 1980, before returning to the UK to join the British Movement as an undercover anti-fascist mole for Searchlight magazine. The British NF, which was seen as the beacon of the CNF, also collapsed after the 1979 election into warring factions. Tyndall formed the New National Front in 1980 and in 1982, transformed this into the British National Party. The remnants of the NF in the 1980s became known as the Official National Front and the NF Flag Group, which competed with the BM and the BNP for support amongst football hooligans and skinheads in the Thatcher years.

(John Tyndall, leader of the NF and the BNP)

In his PhD thesis (acquired through the University of Sydney), Jim Saleam suggests that it was the authorities, particularly ASIO, that stifled the development of the NFA, writing ‘two facts were demonstrated: some Extreme-Rightists had strategies, and the para-State intended they not blossom.’ However while ASIO had infiltrated the NFA from its very inception and monitored it closely, the hostility it faced from the Australian public and its inability to gain any sort of traction politically was more to do with the NFA’s ideology and its membership.

As John Blaxland has acknowledged in his volume on the official history of ASIO, the security services had monitored the far right in Australia since the inception of the NSPA in the early 1960s and continued to monitor the far right throughout the 1970s, even though the various far right groups did not seem to present a danger to the parliamentary system and the ‘poor quality’ of its small membership. Troy Whitford has shown that when National Action was formed in 1982, both ASIO and the NSW Special Branch took measures to monitor and infiltrate the organisation, especially in the late 1980s when NA became increasingly involved in racist and political violence (as noted in the 1991 national inquiry into racist violence in Australia).

These three large files of ASIO’s surveillance of the National Front of Australia make for very interesting reading and show how the NFA attempted to seize the initiative presented by the British NF, creating an antipodean version of the UK organisation. The NFA had a particular pro-British outlook and saw a white-dominated British Commonwealth as its goal, but like many white supremacists and far right activists in the 1970s and 1980s saw South Africa and Rhodesia as symbols of white ‘civilisation’ being attacked by non-white and communist forces. Solidarity with these former settler colonies was paramount to the NFA’s worldview. The files show that the internal structures of the NFA (with the disputes over the leadership and direction of the party), as well as the media’s spotlight on the fledgling group and its inability to gain a widespread following, all led to the demise of the NFA by the early 1980s. However, as National Action, the Australia First Party and nowadays, the United Patriots Front demonstrate, the far right in Australia may change and shift, but not necessarily go away.

Forming the National Front of Australia: ASIO and the fledgling far right group