Stop the Cover-Up of Secret Police Abuses

Demo – Tuesday 22 March

9 – 10am Royal Courts of Justice

The Strand

London

Spycops inquiry: ‘If it’s in secret, it’s dead in the water’

Following the exposure of police spy Mark Kennedy in 2010, activists and journalists slowly began to lift the lid on political policing in Britain. Their investigations found that the state had used undercover officers to infiltrate hundreds of political groups to surveil their activity and attempt to undermine dissent.

We now know that officers commonly used intimate relationships with targets as a tactic, stole the identities of dead children, spied upon families fighting for justice following the death of loved ones in police custody, and lied in court to secure convictions against activists. Disturbingly, internal investigations by state agencies over the same period revealed little.

In 2012, Mark Ellison QC conducted an independent review into police corruption during the Stephen Lawrence murder investigation. The findings were damning. Following increased public pressure, the Home Secretary announced an independent public inquiry into undercover police operations. Lord Justice Pitchford was appointed to lead the Inquiry.

Next week, at a crucial preliminary hearing, Pitchford will consider what legal approach he will take in response to applications to keep information secret. Police agencies argue that much of the Inquiry should be held behind closed doors, excluding both the public and non-state core participants.

Donal O’Driscoll is one of nearly 200 victims of police spying operations already granted core participant status. He is also part of the Undercover Research Group, an organisation which researches and uncovers police spies and assists those fighting for state accountability. He says this is a pivotal moment.

‘This hearing will set the foundations for the rest of the Inquiry. What happens there dictates how the Inquiry will be and how everyone will engage with it. Worst case scenario is that the judge goes for a totally secret inquiry, in which case it’s pretty much dead in the water. Nobody on the non-state side will trust it in any form. In all likelihood there would be a mass walkout.’

Donal O’ Driscoll

Culture of secrecy

The police agencies controversially assert that Pitchford should uphold the practice of Neither Confirm Nor Deny (NCND) throughout the Inquiry in relation to the identity and activities of police spies. If this approach is adopted, hearings will be held almost entirely in secret, and the details of undercover operations, including the identity of officers, will remain hidden from the public. Lengthy submissions from the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), supported by the other police agencies, contain wide ranging assertions to support their view that secrecy is in the public interest – from a duty not to break an alleged promise to officers of ‘life-long confidentiality’ to concerns that exposure could lead to ‘emotional unhappiness.’

‘My impression is that this is desperation’ says O’ Driscoll. ‘They are desperate to maintain their culture of secrecy and their unaccountability; it’s about protecting their reputation.’ Merrick Cork, another core participant in the Inquiry, is also dismissive.

‘They’ll argue anything’ Cork says. ‘The first rule of power is to protect itself. If they were interested in justice they’d want to root out the wrongdoers and the bad practices. The fact that they close ranks shows that they’re not interested in justice; they’re interested in power. NCND is not long standing, nor is it a policy. It’s a relatively recent practice that they pick and choose when to use. It wasn’t until six months into the court proceedings of the eight women who sued the police over undercover relationships that they even brought up NCND.’

Former undercover officer turned whistleblower Peter Francis agrees. He has told the Inquiry he was never promised lifelong confidentiality and that NCND wasn’t mentioned during his employment, nor included in any written documentation relating to his role. His submissions are a significant blow to the police’s credibility.

Worryingly, the Home Office submissions to the Inquiry support the police stance on NCND. Despite claiming to have ordered the Inquiry ‘to [restore] public confidence in the police by uncovering the truth… in as open a way as possible’, the Home Office argues that ‘the public interest in ensuring that police techniques remain effective should outweigh the interest in public access to information.’

‘When I read the Home Office submissions it felt like the whole thing was tipping over into farce,’ says O’Driscoll. ‘The Home Office ordered the Inquiry, set the terms of reference, spoke of all the horrible abuses that took place and now it’s asking for all of that to be kept secret. It doesn’t make sense.’

If the state core participant arguments are accepted next week, the Inquiry could become dependent on self-disclosure by the police, in secret hearings. Considering that serial breaches of disclosure obligations and destruction of evidence by the MPS form the backdrop to the Inquiry, who could have confidence in such a process?

‘We’re victims of serious police misconduct, participating in the public interest to ensure a thorough investigation. We’re not going to walk in and tell our stories in those circumstances. The police can spin a complete set of lies and we’re not going to be able to challenge it. We’re the ones who’ve already had all the intrusion, why would we go through that again if there’s no chance of justice at the end?’ explains O’Driscoll.

In stark contrast to the police position, non-state core participants assert that it is essential that the Inquiry is open and transparent.

Cork and O’ Driscoll are two of 133 non-state core participants who wrote to Pitchford (here) calling for the release of officers’ cover names and a list of the political groups spied upon.

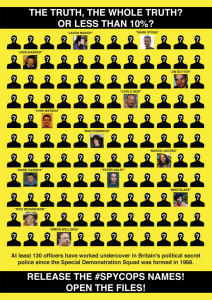

Cork explains: ‘Everything that we got so far, everything that has led to this inquiry over five years, has all come from the 15 officers that have been exposed. This is just 10% of the estimated total number of undercover officers. We need the cover names so people can know they were targeted. The only way we will get the truth is if the people who were spied upon are able to tell their stories. Otherwise we’re only going to get 10% of the truth.’

A key term of reference of the Inquiry is to discover ‘whether and to what purpose, extent and effect undercover police operations have targeted political and social justice campaigners’. If Pitchford accepts the police submissions on NCND next week, the cover names will remain secret. Without their publication, people won’t know they were spied upon and it will become impossible for the Inquiry to fulfill its aims.

As the establishment forces unite to demand secrecy, Pitchford is in an unenviable position.

But if he yields to their demands, the process is bound to fail. As this is a public inquiry, it follows that the starting point must be open proceedings, with minimal restrictions, fully justified on a case by case basis. Those who were spied upon deserve answers. The Inquiry was ordered to help address the loss of public confidence in the police resulting from serious misconduct in undercover operations. If it appears to be a cover-up, the Inquiry will only increase the concerns it was called to address.

To be effective, it must be open.

via thejusticegap, also see policespiesoutoflives

http://325.nostate.net/?p=19336#more-19336