Tutto ciò si scontra con le nostre sicurezze, con il nostro bisogno di ordine, con la nostra stringente logica da ragionieri che determina la nostra quieta esistenza da ragionieri. La tranquillità del nostro sonno e dei nostri affari lo esige, la propaganda statale lo conferma: non c’è nessun genocidio in corso nei territori palestinesi, c’è sola una caccia senza quartiere nei confronti di crudeli terroristi che, per tragiche quanto fatali circostanze, si sta ripercuotendo duramente anche nei confronti della popolazione civile. Ma, se le cose stanno così, che dire del numero tatuato sui prigionieri palestinesi, agghiacciante riproposizione di una delle più nauseanti pratiche naziste? Che dire della distruzione di case e interi villaggi, anche questa praticata un tempo contro gli ebrei (nello specifico, dai soldati inglesi)? Che dire di tutti quei morti – bambini, donne, vecchi – che non possono rientrare di certo nello stereotipo mediatico del terrorista fanatico inneggiante alla guerra santa? Come si vede, non ci sono molte alternative di fronte al massacro in atto: o il silenzio del consenso, al tempo stesso risultato e garanzia della pace sociale, o l’interrogativo del dissenso. Ma questo interrogativo, se portato fino in fondo, fino alle sue estreme conseguenze, che cosa ci riserverà? Saremo in grado di ascoltare le risposte?

fawda

APRIL 2002

“Let’s remember the way other people have treated us and how they still treat us everywhere, as foreigners, as inferiors. Let’s guard against considering what is foreign and insufficiently known as inferior! Let’s guard against doing ourselves that which was done to us.”

Martin Buber, 1929

At the time in which we are writing these lines, the whole world is watching the events that stain the Middle East with blood with baited breath. We don’t know if the tension caused by the military occupation of Palestinian territory by Israeli troops will be so high by the time you read these lines, or if the pressure from international chancelleries will have managed to cool the boiling militaristic spirit of the Sharon government.

That which we know, that which urges us to speak, cannot be exhausted in the facile humanitarian attitude of blame and indignation. In the face of all that has happened, is happening and is being prepared in these apparently distant places, we feel only repugnance for those who live in anguish that the sanctity of the basilica of Bethlehem could be profaned, worried that the divine manger could be soiled by Arab blood; and for those who accuse all who protest against the operations of the Israeli state of anti-semitism, as if this state were synonymous with the Jewish people; and for all those who lay claim to our shock for the lack of light and life of an aspiring Palestinian head of state enclosed within his bunker; and for those who try to place the indiscriminate violence of desperation and the indiscriminate violence of institutions on the same level, with the aim of justifying the latter as a form of defense against the former; and for those who simply want this all to end so that they can continue to fill their cars with fuel without having to spend too much.

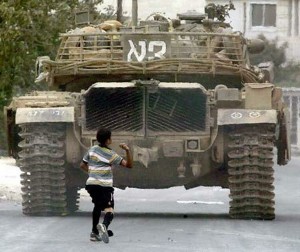

Let’s admit it. Upon hearing the news that comes out of the Palestinian territories, the word that continually comes out of our mouth is not the same one that first comes to our mind. At most, our tongues say extermination – ruthless and sometimes methodical destruction and suppression of a large number of people – while our brain thinks genocide – the methodical destruction of an ethnic, racial or religious group, carried out through the extermination of individuals and the annihilation of cultural values. Genocide is much more than extermination. But this is a term that we somehow refuse to use, because its use in such a context would undermine the foundations of many of the certainties on which we have built our world, its tranquility and its prosperity.

How can we call that which the Sharon government has undertaken genocide after being told over and over again so many times that genocide is an atrocity of the past, fruit of the worst obscurantism, that could not find legitimacy in a Western democracy (as, in conclusion, Israel is)? And then, having been victims of the genocide carried out by the Nazis, having suffered infamous persecution, how could Jews today, who recognize themselves in Israel, wear the butcher’s apron and do to others what they were forced to suffer in the past? All this comes into conflict with our security, with our need for order, with our cogent bookkeeper’s logic that determines our quiet bookkeeper’s existence. The tranquility of our sleep and of our affairs requires it, state propaganda confirms it: there is no genocide under way in Palestinian territories, there is only a hunt without quarter in the face of cruel terrorists that, due to circumstances that are as tragic as they are fatal, is having harsh repercussions for the civilian population as well. But if this is how things are, what can be said about the numbers tattooed on Palestinian prisoners, a chilling reiteration of one of the most nauseating Nazi practices? What can be said of the destruction of houses and entire villages, again something that was practiced against the Jews (specifically, by English soldiers)? What can be said about all the dead – women, children, old people – that could surely not be included in the media stereotype of the fanatical terrorist extolling holy war?

As is clear, there are not many alternatives in the face of the massacre that is going on: either the silence of consent, which is at the same time the result and the guarantee of social peace, or the questioning that springs from dissent. But, if it is carried to its conclusion, to its extreme consequences, what will this questioning leave us? Will we be able to listen to the answers?

Actually, if the Nazi genocide against the Jews was the first to be judicially condemned, nevertheless it was not the first to be perpetrated. The history of western colonial expansion into the 19th century – that led to the creation of great empires on the part of the largest and most powerful European states – is first of all a succession of systematic massacres of indigenous populations (the greatest of these being the genocide of the Native American populations that occurred after 1492).

In a few words, genocide is a weapon that the state has always used. And it would be a gross error to think that recourse to mass extermination on the part of the state could only have happened in the past, when the ambition to conquer new economic markets goaded the crowned heads of Europe to launch their subjects on adventurous enterprises beyond their borders. In reality, although the practice of genocide was more readily visible during colonial expansion, it also occurred – and still occurs – within the borders that a state gave it self in its formulation as well as its consolidation.

The history of the United States is exemplary in this sense. Even the glorious and democratic United States was born through genocide, that carried out against the Native Americans by an army sent out to protect colonists of European ancestry in the name of a “freedom” obtained by destroying villages and slaughtering entire populations of Indians (naturally arousing their resistance that sometimes assumed ferocious hues even against the civilian population). We all know how it ended: the United States government took possession of all the territory once possessed by the Indians, while it allowed the few that survived to live on cramped and unhealthy reservations, bewildered by various kinds of western consumption and reduced to folkloristic phenomena and tourist attractions.

The European states themselves were the first to know the relative homogeneity of today, but they also had to come to terms with the resistance of numerous ethnic minorities. If the Basque or the Irish question still has some currency, it is only because these people’s struggles have managed to extend themselves to our times.

But what is it that makes the state intrinsically genocidal? It is its pretence of forcing that which is in fact separate into a fictitious unity. The suppression of difference is part of the normal functioning of the state machine, which systematically proceeds to standardize social relationships. The state does not recognize individual with differences between them and thus unique, but only citizens who are equal before its authority and therefore identical. A state can only claim to be formed and proclaim itself absolute and exclusive holder of power only where and when the population over which it exercises its dominion speaks its language, respects its laws, follows its customs, uses its money, practices its religious faith. When this reduction, this homogenization cannot be carried out through formally peaceful methods, the state uses violence. Through genocide, the state merely brings the elimination of the Other to term, and indispensable moment for imposing its authority and thus realizing the unity it needs.

If the state was genocidal already in antiquity, things certainly didn’t change with the advent of capitalism, which tends to always extend its borders in the ongoing search for profit. The globalization that is so frequently denounced, in other words, the transnational capitalism that is transforming the entire planet into a single, giant supermarket, is a perfect example of this.

Nowadays, instead of physically exterminating an indigenous population, it is preferable to culturally convert it after having economically and politically vanquished it. Capitalist society is not only the most formidable mechanism of production ever developed by humankind. It is also the most terrifying machine of destruction and standardization. Culture, society, individual, space, nature…everything is exploited; everything must be exploited. Here it is made clear why the state gives no rest to social organizations that leave the world to its tranquil, native unproductiveness. The fact that tremendous resources lie unexploited is intolerable for western culture, which in the course of history has imposed the customary dilemma: either start walking on the path of productivity or disappear. Capitalist civilization deconstructs and destroys all non-capitalist social forms, everywhere imposing the model of the atomized citizen – basic to democracy – incapable of possessing a social existence outside of the abstract and homogenizing mediation of money, work and the state. If Israeli soldiers today behave in more or less the same way toward Palestinians as German soldiers behaved toward Jews sixty years ago, it is not because Jews and Nazis are the same as boorish anti-semitic propaganda would have it, but because in every era, soldiers are alike. It is the task of the army to destroy everything that might cause the ruin of the state. Hitler held that Jews represented a threat to Germany and therefore tried to exterminate them. Sharon thinks that Palestinians constitute a threat to Israel and therefore wants to exterminate them. Now the problem is not the Jewish people, but rather the state of Israel. Hypothetically, if things were to be reversed tomorrow, the problem would not be the Palestinian people, but its state (that would probably try to exterminate the Jews if it were given the opportunity). In other words, a solution to the Jewish-Palestinian conflict will never be able to be found if it remains within institutional logic, political mediation and treaties between states.

After the attacks of September 11, 2001 – since now in the imaginary of the western world, the “Arab kamikaze” inspires the same terror as the “scalping redskin” provoked at the end of the 19th century – the government of Israel has decided to take advantage of the situation that has been created in order to take another step forward toward the final solution to the Palestinian problem. If the United States bombs Afghanistan [and soon maybe Iraq] in the name of the struggle against Arab terrorism, why shouldn’t Israel raze Palestinian territories to the ground in the name of the struggle against Arab terrorism?

One can understand how the western states could not help but lean toward favoring the Israeli state. How could they forbid it from doing what they themselves have done (against the Native Americans, the inhabitants of the Indies, the black Africans, the Algerians, not to mention the beautiful Ethiopians with their black faces)? How could the western states condemn the Jewish state after all that their predecessors have done to the Jews?

Not one impediment, not one condemnation. Only the requests for moderation and mild criticism. At worst, the application of a few sanctions. “If you exterminate a population, the importation of your grapefruits may possibly be temporarily suspended.” But since the endeavor of genocide against the Palestinian people is in course and no one can ignore it, there is only one path left for the western governments to follow. To save the Palestine by transforming it into a state, to offer the Palestinians the same compensation offered to the Jews after the second world war. When a government exterminates an insubordinate population down to its last member, this is a matter that can be justified and is amply justified by the reason of the state. History, as we have seen, abounds with analogous examples. But in the contemporary world, cannibalism between states is not permitted (which explains the haste shown by Sharon to definitively “clear out” the occupied territories…of Palestinians). If they want to survive, the western democrats insist, the Palestinians must become like us. It is necessary to help them in such a way that the will have a proper parliament, police, a magistrature, factories, shopping centers, McDonalds, soccer championships, television with so many fine soap operas and – why not? – perhaps its own music festival.

“Two people, two states” is the aberrant slogan that is going around these days as the panacea for the current conflict. In this way, the Palestinians find themselves between the devil and the deep blue sea; either they disappear from the face of the earth or they dying under the Israeli army’s stick, or they convert to capitalist civilization eating the carrot of American and European diplomacy. In either case, the outcome is the same: the Palestinians cannot choose for themselves how to live.

This is where Arafat, the leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization enters the scene, who has been working as a shrewd politician for a decade on the formation of a Palestinian state. Despite the hatred that the Israeli rulers (as well as some Arabs) nurture toward him and the ostracism by American rulers, Arafat continues to have a central role in the path toward normalization. It is no accident that all the governments of the world have urged Sharon not to touch him. They have reason. Just as an enlightened boss will always prefer to negotiate with union leaders rather than meet with angry strikers, in the same way, the more intelligent western rulers prefer to deal with an enlightened bourgeois like Arafat than with a band of excited rebels against modern reason. Despite everything, he remains the leader of the only organization capable of enclosing the Palestinian in revolt within a framework.

The PLO draws its strength from its ambiguous nature. With its weapons, the financial power of the Palestinian diaspora, its international support and its offices in the United Nations, the PLO is an embryo and a caricature of a state, with all that this entails in terms of sordid appetites, struggles between functionaries and direct oppression and fierce repression of dissidents in the zones that it administers. But since it has not yet formed a nation state, it is also the political organization within which human relationships conserve the signs of an ancient solidarity. One of its leaders, who will be nothing but a power-hungry politician in the future Palestinian state, still manages to maintain a direct relationship with combatants who acknowledge him today. What is true of the PLO is even truer for the organizations to which the population has dedicated itself on the spot. The cadres of the popular committees are generally made up of militants from the various parties or sympathizers of the PLO, but the totality of the tasks (surveillance of the movements of the army, provisioning, medical first aid) is carried out by all, young and old, men and women, and the mysticism of death in battle serves as the cement.

Despite being viewed with viewed with distrust by the Palestinian rebels themselves, and increasingly so after the arrest of numerous extremists as a sign of good will launched toward western public opinion, the PLO nonetheless remains the central identifying point of reference for the Palestinians people.

For us, as enemies of every state and fatherland, it is easy to fall into the temptation of setting the uprising of the Palestinian masses in radical opposition to the negotiations and even the armed actions carried out by the various groups linked to the PLO, in other words, to distinguish the Palestinian people from the rackets that claim to represent them. In reality, it is undeniable that the nationalist demand lives in the hearts of the Palestinian rebels, just as it is undeniable that the more spirited military actions have contributed to creating the mystique of the martyr in the entire population and particularly among the youth, which has helped to excite the minds and generalize the courage that could be seen at work in the first intifada (that of the stones), and that now feeds the second. This does not remove the reality that the existence of such a mystique is, at the same time, one of the clearest signs of the limits of this revolt in nationalist form for the social spirit.

One can understand how long decades of oppression and the lack of any prospects for living could be transformed into the love of death in battle. But understanding does not mean sharing this feeling. The act of blowing oneself up in the middle of a supermarket doesn’t only lead to the suicide of a single combatant, it leads to the suicide of the entire struggle of the Palestinians for freedom. Beyond being ethically repugnant, it is tactically harmful. We are not among those who say that its error is that it provokes repression by the Israeli army, which certainly has no need for such pretexts in order to carry out its violence, or that it causes the peace treaties to fail, since there can be no peace where oppression reigns. Rather its error is above all in annulling and adulterating the reasons for the Palestinian struggle behind the rage of desperation. Despite the flags and sacred texts in which they get wrapped, these reasons are universal. The desperation is blind, capable of great strength, but deprived of an outlet. Palestinian terrorism – unlike that of Israel, which is an expression of power – is synonymous with impotence, in the immediate sense because it is not is not capable of destroying the Israeli state, and in the long run because it will end up alienating the solidarity of rebels through out the world including those in Israel. When they wreak havoc among bus passengers or market-goers, they are not, in fact attacking the Israeli state, but rather the population. Giving substance to an indiscriminate violence only corroborates the accusation of anti-semitism that is attributed to them, enclosing them more and more in a nationalist dead-end. Clouded by an understandable hatred, hundreds of Palestinians are ready to die without asking themselves how or why or against whom or for what. The blindness of the method renders them blind with regard to the purpose of the struggle as well. This is why one becomes either a soldier of the PLO or a devotee of the Party of God (Hezbollah) or the tool of a sheikh and his zeal (Hamas). This is not, in fact, due to any supposed “nature” of the Arabs, a conception that tries to hide its racism – Arabs, you know, are reactionary! – behind the recognition of cultural differences.

For centuries, Palestine has been a crossroads for people, site of thousands of cultures that were able to live together without tearing each other to bits by turns. If it has become the land of the most extreme fanaticism, it is because this situation responds to specific interests. And while a sixteen-year-old girl blows herself into the sky, the political and religious leaders who indoctrinated her expect to collect these interests, fruit of this sacrifice as well. Palestinian terrorism thus ends up being useful only to the state: the Israeli state because it allows this state to demonize the Palestinians, and the future Palestinian state because it invokes the recognition of this state as the only way to avert the terror.

Naturally, there is a line of rupture between the potential for revolt against the totality of a world that has produced unbearable conditions of existence for the Palestinians and the attempt to snatch a niche within this world (the Palestinian state) from this revolt. But this line is subtle and continually changes. It uncoils inside the base organizations, the social groups, the moments of struggle and through the individuals themselves, their thoughts, their feelings and their activities. But for now, there is no use in hiding it, doesn’t have much possibility of taking place considering the lack of non-nationalist social movements with which to associate. Above all, the absence of any possibility for common struggle with Israeli exploited must be considered. It would be a mistake to think of Israeli as a homogenous and monolithic society. In reality, its structure is forcefully differentiated. For example, behind the beautiful rhetoric about the unity of the Jewish people hides the division between the Sephardic and the Ashkenazi Jews (not to mention the Israeli Arabs, the lowest rank on the social pyramid). The former are those who originate in Mediterranean lands and form the poorest sector of the population; the latter are those with origins in western* Europe and the United States and form the political and economic elite. To which of these two classes do the Jewish colonists who currently live within the occupied territories and are most exposed to Palestinian reprisals belong? They are Sephardic Jews, of course. Just as in past centuries colonialism also served the European states splendidly as a method for averting social tensions that existed within them, creating an external safety valve, so today the state of Israel finds its national unity in the struggle against the Palestinians.

As long as the exploited Jew and Palestinians will not acknowledge their shared condition, that is to say, will not acknowledge it together, both of their struggles will be crippled, deprived of the possibility of intervening in the ongoing conflict in a revolutionary direction.

As for ourselves, in affirming our solidarity with the oppressed Palestinians, we have no intention of romanticizing their condition. Instead, we intend to show what is universal in their resistance and to oppose the pacifism that wants a smooth transition toward the eternal silence of the market with the social war against all those who support the genocide of the Palestinians (first of all, the Israeli state which has interests that are not so far from us) or their institutional civil domestication (all other states including the PLO).

As is evident, it is not a question of supporting a Palestinian state. We do not want to find ourselves one day united with old victims who have become butchers, with a national capitalism that oppresses the proletariat on its own account, with rulers who were indulgent in the face of the intifada and later transformed themselves into bureaucrats, exploiters and torturers. We don’t want to support a Palestinian state that follows the example of the Israeli state by drawing the justification of its future atrocities from the substantial memories of the misfortunes of the past. Thus, it is not about forcing the Israeli state to respect the rights of Palestinians, nor supporting the formation of a new Palestinian state. Rather it is a question of starting to practice desertion, refusal, sabotage, attack, destruction against every constituted authority, all power, every state.

May the Church of Bethlehem get razed to the ground if this will serve to free the Palestinians. May Arafat die of hunger and thirst, if this will signal the end of the Palestinian authority. May the desperation break loose with rage, if it will know how to direct itself against the Israeli army. May our automobiles remain stalled in the middle of the streets, if this will overturn our resigned complicity with the genocide that is going on. May the Jewish-Palestinian dispute that enflames the Middle East change into the social dispute capable of blazing throughout the planet, if this is the only possibility for putting an end to the slavery that is imposed everywhere by money and power.

the Friends of Al-Halladj

When and How It Started

For centuries, the Jews have experienced the Diaspora, their dissemination throughout the entire world. Lacking a territory in which to root themselves, where their institutions could solidify, the Jews had no state, but formed a community in continual motion. Their attachment to their cultural and religious traditions was such that it rendered their integration into the societies where they settled difficult, if not impossible. In a certain sense, one could say that the Jews were strangers wherever they found themselves, something that contributes not a little to creating diffidence in their interactions (let’s consider what happens even now to another nomadic population that is the victim of persecution, the gypsies).

At the end of the 19th century, Zionism was born. Started by Theodor Herzl, it was a movement that wanted to give the Jews a national seat that could provide a refuge from anti-semitism and injustice. Thus, Zionism sought to offer the Jews who were scattered throughout the world a common fatherland in Palestine under the protection of the great European colonial powers.

There were a few problems however. At that time, the Palestinian territory was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire and was already inhabited primarily by Arabs. Zionism began to be supported by European state, England in particular, because it served as a point of support for opposing Turkish hegemony in the region. It is also said that behind the façade of noble proposals, the founders of Zionism pursued goals that were not exactly philanthropic. Their intention was primarily to preserve the stability acquired by the western European Jews of which they were a part, which was threatened at the time by the migration of Jews coming from the east.

In other words, Zionism was a nationalist movement that originated in class considerations; it was the attempt of the rich Jewish bourgeoisie that was concentrated in Western Europe to defend itself against the influx of the Jewish proletariat – concentrated in the east – that was crossing borders in search of fortune and to save themselves from the pogroms. Quite quickly, these poor Jews began to constitute a problem for the rich Jews, because their progressive increase – as well as their strongly socialist ideas – began to enrage public opinion and western rulers, in a certain ways fomenting anti-semitism, So it was necessary to put a restraint on this migration, to find another place for all these people to go. The choice of Palestine naturally imposed itself, given the survival of a cultural tradition among the eastern Jews based on the messianic hope of a return to the land of Israel.

This is why oppressed Jews have experienced Zionism as a movement of emancipation, not conquest. One could say that, from the beginning, the Zionist enterprise has been distinguished from all the others by its extraordinary good conscience that carried it forward, because the myth of the return to the promised land added its exultant representations to the more classic ones of civilized colonialism. Many of the Jewish colonists who set their poor feet in Palestine were undoubtedly animated by noble proposals, being for the most part either survivors of persecution who only desired to be free or convinced socialists inclined to build the “new world” without having to wait for a social revolution that never seemed to keep its promise of liberation. The price to pay for the enthusiasm that arose for Israel with its kibbutzim and its pioneering mentality was a kind of bungling ignorance that has struck generations of colonists. For a century, the Zionists have resorted to every kind of denial, mystification and lie in order to hide what leapt before their eyes from the beginning: there were already people living in the place where they had settled.

The Jewish colonists who arrived at the beginning of the 20th century began building Israel on an ancient myth: the desert. Their slogan was: “A people without land for a land without a people.” This does not mean that the Zionists arrived in Palestine believing that they would find no one there, but rather that they were the product of a particular culture. Where there were non-Europeans, this culture saw emptiness; where there were Bedouins, it saw a desert to make bloom; where there were stubborn villages, it saw a land to liberate.

The discovery of the Arab inhabitants of Palestine, their agricultural and commercial structures, their cities, their villages, their culture and, above all, their national aspirations, was an unpleasant surprise for the Jews. Initially, when their presence in Palestine was not nearly so massive, their relations with the Arab inhabitants were mainly those of mere exploitation. With money from the Zionist coffers, the Jews had acquired the lands of the owning sheikhs and made the Palestinian peasants work for them. But this labor force, however convenient became superfluous once thousands and thousands of Jews began to flow into the fatherland that had finally been recovered, still under the goad of anti-Semitic persecution. In 1904, the influence of the socialist tendency, which was against the exploitation of Arab labor, became preeminent within Zionism. The colonists could no longer force Arabs to work while underpaying them, but rather had to work themselves in their kibbutzim with a wage equal to that of qualified European workers. Paradoxically, the socialist politics of work developed directly by the Jews put an end to the initial exploitation of the Arabs, but also caused the exclusion of the Palestinians from the Jewish economy, a prelude to their expulsion from the land. The Jews had bought the land; the Jews worked it. So there were now too many Arabs. The relations between Jews and Arabs, which had been tense up to that time, collapsed definitively with the first world war, when the interests of the British empire were revealed in the light of day.

In 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered the war, allying itself with Germany. In 1915, England promised independence and sovereignty to the Arabs in exchange for a revolt against Turkish domination. In 1916, unknown to the Arabs, England made arrangements with France and Russia for the partition of the Ottoman territories in the Middle East. In 1917, the famous Balfour declaration was issued in which the English Minister of Foreign Affairs promised British support for the formation of a Jewish national seat in Palestine to Edmond de Rothschild. In 1918, Palestine was occupied by British troops who came there to allow the British administration as established by the League of Nations. Three years later, in 1921, the Balfour declaration was embodied in the British Mandate over Palestine.

At this point, the situation could only get worse. The Arabs felt betrayed by the English who had not only not granted the promised independence, but who were furthermore supporting the Jewish settlements that grew larger every day. From their side, the Jews saw nothing more that a form of anti-Semitism in Arab hostility, since they had paid for these lands and managed to make them bear fruit through hard work. For the Arabs, the Jews were nothing more than invaders protected by the British. For the Jews, the Arabs were nothing more than uncivilized and fanatical anti-Semites. Nationalism began to spread on both sides. The few discordant voices, like those of the Jewish anarchists, who supported a bi-national Judeo-Arab movement on the basis of kibbutz socialism, or those of the Palestinian communist party that favored proletarian internationalism, were not heeded and were quickly drowned out by the chauvinistic hysteria. Violence became increasingly commonplace and brutal on both sides. The rights of both only left space for wrongs. The more time passed, the clearer it became that the land was much two small for the two peoples to be able to live there: one of the two had to vanish in order to allow the other to survive.

With the end of the second world war and the defeat of nazism, the Zionists succeeded in getting all of the democratic states to share their vision of the future of Palestine, playing off the bad conscience of the rulers and the populace who – especially in Germany, Italy and France – had compromised themselves by spreading anti-Semitism. The creation of the state of Israel, at the expense of the Palestinians, was the compensation due to the Jews for the suffering that they endured. The proclamation of the state of Israel occurred on May 15, 1948. The creation of the state of Israel, at the expense of the Palestinians, was carried out through the same methodology used by other capitalist states at the time of their formation. The creation of the state of Israel, at the expense of the Palestinians, was useful to western interests that preferred a certain instability in the Middle East to forestall a possible unification of the Arab world. The creation of the state of Israel, at the expense of the Palestinians, made the rich, well-fed Jewish communities existing in the West happy, with all that this entailed in economic terms. Thus, the state of Israel was recognized by all the western democracies as on of their kind.

As the supreme representative of the victims of the supreme anti-democratic horror – nazism – Israel could thus administer a symbolic capital all the more powerful because the neighboring lands are in the hands of dictatorial regimes that don’t hesitate in resorting to violence against their own populations (particularly Palestinians) when necessary. And since the state of Israel cultivated a form of democracy that would like to resemble that of ancient Greece – where the “freedom” of the citizens was based on the slavery of the helots – it was consecrated as the local representative of democracy and western reason, bulwark against the shadow of Islamism. The state of Israel can therefore cause terror to reign all around itself, firm in its super-right, proud of its super-good conscience. This does not prevent it from being condemned to practice a politics of separation at its interior and aggression at its exterior in order to survive. Meanwhile the constant reminders of the misfortunes suffered in the past by the Jews only serve as moral justifications for covering up the horrors carried out in the present.

http://guerrasociale.altervista.org/fawda_ing.htm

========================================================