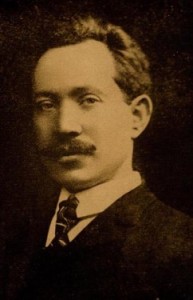

Max Staller (1868-1919)

[An earlier, much shorter version of this article, “Anarchists in Medicine and Pharmacy: Philadelphia, 1889-1930,” appeared in Clamor Magazine #6

(Dec. 2000/Jan. 2001), and had previously been posted on both the Guinea Pig Zero and Dead Anarchists websites. – Ed.]

In the City of Philadelphia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a large group of professionals who practiced medicine or pharmacy as a livelihood, while committing great energies to the anarchist movement. Looking past the surface, we find a closely knit community of intellectuals who treated their comrades as patients, educated the public on health related matters, and who contributed substantially to the cause with money or the use of their facilities.

A look through the anarchist literature of the period will reveal the names of a remarkable number of doctors, who pioneered many of the debates on social changes that are, by and large, taken for granted today. Among them, the best known is undoubtedly Ben Reitman. He is so noted because he catered to the mainstream Media image of an anarchist by hanging out in saloons and hobo jungles, once carrying on a comic chase scene with detectives through Philadelphia’s department stores, and generally keeping himself in the realm of romantic legend. While Reitman did his share of fighting for positive social change during his career, he was the very least distinguished of the anarchist physicians of his time. Certainly some of his leading contemporaries made this assessment. He was actually more a political performance artist than a doctor. Reitman’s relative prominence is largely due to his personal connection to the very famous Emma Goldman, but even more due to the fact that almost nothing has been written in English about the doctors whose work, both in anarchism and in medicine, simply eclipsed the career of the “hobo king.”1

Such is not the case in Yiddish, but not so many people use that language these days, nor is it easy to locate the books by and about Jewish anarchist doctors. The major figures already known had careers in New York. They include Hillel Solotaroff, Jacob Abraham Maryson , Michael A. Cohn, and Abel Braslau, all of whom were active in the movement in addition to being respected, practicing physicians. While New York’s anarchist doctors and their contribution to the movement is known and thoroughly documented, their colleagues in Philadelphia have been almost completely forgotten.2

A central event in the tale of these particular comrades was the shooting of Voltairine de Cleyre by an insane former language student of hers named Herman Helcher. Voltairine was already fairly well-known in the international movement for her many essays and poems that had been published in anarchist and other radical periodicals. Locally, she was one of the two best-known anarchist speakers, along with a self-educated English-born shoemaker named George Brown. She earned a very modest living by giving private lessons in English, French, and Piano. This poor but respected woman was wounded by three revolver shots on December 19, 1902 at the corner of 4th & Green Streets, as she waited for a trolley car.

The early reports had it that Voltairine was doomed. She had been taken to Hahnemann Hospital, where the inside of the anarchist medical world begins to reveal itself. Daniel A. Modell was a 40-year old general practitioner and socialist, as well as de Cleyre’s “family doctor.” Modell lived in her neighborhood (which is where she was shot) and was yet another of her former students. His son David was an anarchist who translated Russian texts into English. Modell rode with her in a horse-drawn police wagon to the hospital, and his presence at the bedside is no surprise, but mentioned along with him was none other than Dr. William Williams Keen, who was at that time one of the leading surgeons in the world. Already revered for having removed a cancerous tumor from the jaw of President Grover Cleveland nine years earlier, Keen in 1902 was co-chair of Surgery at Jefferson Medical College. He had already served as the President of the American Medical Association, and he would later preside for ten years at the American Philosophical Society, then the most distinguished scientific think-tank in the country. He had been teaching surgery at Jefferson since 1889. Keen was consulted for a possible operation, but he had no affiliation at all with Hahnemann Hospital. He recommended moving the patient to his own offices, but this was never done. Her condition started to improve, and finally the bullets remained inside her for the rest of her life. Daniel Modell, unlike many doctors he knew, is hardly traceable on history’s radar except for the fact that he was de Cleyre’s doctor when she was attacked.3

Dr. Keen happened to be a leading advocate of animal vivisection, and a vivisector (or “fogey”) himself. This placed him on the opposite side of an intense and ongoing debate from Voltairine and many anarchists of her day. As she recovered, Charles Leigh James, a pro-vivisection anarchist chided her for having been in the same room with a fogey. De Cleyre replied that she’d had no more choice in choosing her physicians than would a vivisected dog.4

Aside from the problems of the bleeding lady anarchist, we need to ask ourselves just how the best medical talent on earth came to have anything to do with it. Voltairine was a poor person, who would do well to get help from even a mediocre physician at a time like that. Who had brought in the big gun, and how? The precise answer is out of our reach, but we can narrow it down to two of Keen’s former students, Leo Gartman and Bernhard Segal, who graduated at Jefferson in 1894 and 1893, respectively. Both were both quite active in the local anarchist movement at the time. Dr. Gartman may have still been on the house staff at Jefferson Hospital, where he practiced urology before going into private practice nearby at 525 Pine Street.

Leo Noy Gartman (c.1865-1930) was born to a somewhat wealthy German-Jewish family in Ekaterinoslav in the Ukraine. At age seventeen, Leo left the Russian Empire with his family during a period of widespread pogroms, new anti-Jewish laws, and mass emigration that followed the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. The Gartmans joined the Am Olam movement, a self-emancipating agricultural project that established Jewish farm colonies in the United States. Arriving in 1882, they were one of the original settlers at Alliance, New Jersey, which was one of several Am Olam projects in the southern part of that state. Two other early Alliance settlers who we find later among Philadelphia anarchists were George S. Seldes and Moses Freeman. The Gartmans stayed there for six or seven years, and then Leo and two brothers started a small cigar factory at 7th & Passyunk in Philadelphia around 1889. One of the brothers remained in the cigar business. A fourth brother became a jeweler.5

Leo had been educated in Germany, which made him a higher-qualified candidate for medical school than the average. Prior education was preferred at the time, but not required in most institutions. Before entering Jefferson, he had won a fellowship in mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania, but we cannot verify that ever used it. During the 1890’s, Leo was an amateur stage actor in Russian-language productions of plays by Chekov and Gogol. Dr. Gartman, according to his family folklore, had a “large female practice, including many fast women.” He was a disciple of Havelock Ellis, the great birth control advocate and sex psychologist, and also the evolutionary theorist and freethinker Ernst Haekel, after whom he named a son. He specialized in the treatment of venereal diseases. Leo lectured at meetings held by the anarchist-led Social Science Club from mid-1901. Stories of Leo Gartman at Philadelphia often mention that he was extremely overweight. He was also opposed to circumcision, and he would bring his daughter Naomi with him on house calls in a two-seat automobile, and help her with her homework every night. The famous Russian novelist Maxim Gorky visited with the Gartmans during one of his 1906 visits to the city.6

The anarchist Bernhard Segal (1868-1923) was a highly respected pediatrician. Arriving in the United States at age 20, he immediately enrolled in Thomas Jefferson Medical College, where he graduated in 1891. Segal was a co-founder of the Mt. Sinai Dispensary on Pine Street. His obituary in the Evening Bulletin stated that “he first established his practice at 5th and Queen Streets, where he became a charity physician, caring for the poor at no charge. Later he acquired a reputation as a children’s specialist.” At the time of his death, his three daughters Vera, Louisa, and especially Vivienne all were well-known stage actresses.7

When Voltairine was shot, she earned the lasting respect of both her anarchist friends and the general public by her flat refusal to testify against her assailant, who was a familiar face in the anarchist scene. Her friends took this a step further by hiring two lawyers for his defense and calling for him to receive mental health care. Herman had been effected by typhoid fever around 1896. His sister told reporters that it had “left him a different boy,” and that it had made him “morose and melancholy.” Another local physician, also an anarchist, evaluated Herman and seconded his family’s recommendations. It was Dr. Simon M. Dubin (1867-1919) who owned a house at 327 Pine Street, where he lived with his family, a servant, and a few tenants. Dubin had taken his medical degree in Berne, Switzerland in 1896, and specialized in psychiatry. One of Dubin’s earlier tenants had been Herman Helcher for some years, and Natasha Notkin, a prominent nihilist/anarchist and close friend of Voltairine’s, lived there in 1900. This may have been where Emma Goldman stayed during some of her speaking visits as well, since she was accustomed to overnight with Notkin.8 Dubin would later be active in raising funds for the unsuccessful Russian revolutionary cause of 1904-06.

Anarchists all over the country leapt into action on behalf of their wounded friend, including Emma Goldman, who called for material aid, and Dr. Hillel Solotaroff, who approached another physician on her behalf. That other doctor was Samuel Gordon, which brings us back again to Pine Street.

Samuel H. Gordon (1871-1906) was not only a former anarchist, but also a former lover of Voltairine’s. Their stormy, intense relationship lasted about six years, but had been over for quite a while. Gordon was not popular among the other anarchists, and he was regarded as shallower and less intelligent than his companion. The lovers’ chief source of quarrel was her refusal to fall in line with Gordon’s wish for her to be domestic and wife-like. While de Cleyre and Gordon were intimately involved, he enrolled in Medico-Chirurgical College in Philadelphia, and she began giving him money from her meager earnings to help him through school. By the time of his graduation in 1898, Gordon had become disinterested both in Voltairine and the anarchist movement. In her letters from the few years following, she describes him as conceited, inconsiderate, and getting rich and fat on his new profession. He set up his practice at 531 Pine, just four doors over from Leo Gartman’s home and office. Thus, the anarchists who were scrambling to save their wounded comrade just before Christmas in 1902 had every right and reason to approach Gordon for help, so Dr. Solotaroff came down from New York and asked him in person.9

To Solotaroff’s surprise, Gordon refused to give help of any kind, and wanted nothing to do with the whole affair. Emma Goldman and other anarchists despised him bitterly for this. Dr. Gordon died of “acute gastritis” on November 10, 1906, after relocating to Newark, New Jersey.10 Further research is needed to answer the remaining questions, but one cannot help but wonder whether the anarchist doctors made a medical practice unfeasible for “that dog Gordon,” as Goldman would later remember him, by shunning him in their professional circles. He had alienated some of the most prominent physicians in the city, and several of them lived and practiced close by him in the Jewish quarter. Voltairine took years to become active again, and suffered severe pain from her wounds until her death. Dr. Gartman took over her medical care by spring 1905, and turned her around from her lingering illness and depression within a few months. Leo Gartman emerged as a friend and comrade when he posted $800 bail after her arrest for incitement to riot in 1908 –a very substantial sum –in the middle of an economic depression.11

Another anarchist who knew Gordon and who figures prominently in the medical scene of his time was Max Staller (1868-1919) who –along with his anarchist comrades Leo Gartman, Bernhard Segal, and Simon Dubin –established the Mt Sinai Dispensary at 236 Pine Street, opening its doors in May, 1900. This clinic filled the need for free or cheap health care for the thousands of poor Jewish factory workers in the neighborhood, who often suffered from tuberculosis and venereal diseases. Gartman served as its first treasurer, Staller as its first president. In later years, as the dispensary evolved into a hospital, Staller stayed on as a visiting surgeon. Mt. Sinai hospital survives until it was ruined during a general meltdown of the city’s health care system in October 1997. What was begun by anarchists was destroyed by corrupt capitalists.12

Staller also played a leading role in organizing the Jewish Consumptive Institute and the local branch of the County Medical Society, both in 1910. After returning from Chicago with his medical degree in 1895, Staller and his wife Jenny were active in staging amateur Yiddish plays with a group they called the Star Specialty Club. Earlier still, Staller was a member of the Knights of Liberty, the Jewish anarchist group which had counterparts in other U.S. cities from 1889-1893. Nicknamed the “Boy Chieftain,” and called “the best speaker on the Jewish street,” Staller served as the manager of a successful strike by the ladies’ cloak makers in 1890, and was arrested on one occasion while trying to avoid the police by fleeing through a window to the fire escape. He was charged with making an incendiary speech and inciting the audience to riot, but he denied having done this and was acquitted. Gartman and Staller lie buried quite near to each other at the Montefiore Cemetery in suburban Jenkintown, their graves marked with impressive stones.

Aside from the doctors, there were several pharmacists on the anarchist scene in Philadelphia who had an impact on the movement that derived, in large part, from their profession. Jacob L. Joffe was involved in the anarchist movement at least as early as 1901, when Voltairine de Cleyre mentions in a letter to her mother that her friend, Esther Berman, was learning the pharmacy craft in the shop owned by another friend. Berman seems to be the same person as Esther Wolfe, who in 1905 became a partner in the Joffe & Wolfe drug store at 701 South 3rd Street. Another young woman to learn the profession through an apprenticeship with Joffe was the aforementioned Natasha Notkin, a Russian-Jewish nihilist who came to the US in 1885, at age fifteen.

Although only one small newspaper sketch of Notkin’s face survives, there are many reports of her, all through the years from around 1890 until 1917. As a member of the Knights of Liberty, she took part in organizing the Yom Kippur Balls, a short-lived effort to draw working-class Jews away from religion by arranging social events during the high holidays. When two of her comrades stood trial for incitement to riot in 1891 after a meeting was raided on the night before one of the balls, Natasha was called as a witness for the defense. Some four decades later, her court appearance was recalled by a comrade. She was wearing her hair bobbed, then the habit of dissident Russian women, and she treated the prosecutor with contempt.

“Are you a nihilist?” He asked.

“I don’t know what that means,” she replied.

Both before and after opening a drug store with Joffe in 1907, Notkin was the Philadelphia distributor of the anarchist papers Free Society and Mother Earth. In 1892, Natasha had co-founded the Ladies’ Liberal League (LLL) along with Perle McLeod, a Scottish-born anarchist who may have received training as a nurse in later years, Mary Hansen, who originally came from Denmark, and Voltairine de Cleyre. The LLL was a secular venue for public lectures on a wide range of social topics, and medical doctors, both male and female, figured prominently on the speakers’ list. The venue seems to have been a means by which radical physicians aired their views to the public. The non-anarchist guest speakers from nearby institutions included Dr. Henrietta Payne-Westbrook, a local practitioner and author who advocated marriage; Dr. Frances Emily White, a poet and medical education reformer from Women’s Medical College, and Dr Michael Valentine Ball from Eastern State Penitentiary, who spoke against current beliefs on criminology, wrote articles on the conditions of Negroes and on drug addiction, and with whom Leo Gartman co-authored a short article on a burn case in 1897.

Finally, the anarchist and single-taxer George Sergius Seldes (1860-1931) ran a pharmacy at 946 South 5th Street from 1899 to 1906. Born near Kiev, Seldes was a Russian Jewish intellectual and a major force among in the organization of intentional communities throughout his life. Like Leo Gartman, Seldes came to the US with the Am Olam movement in 1882, when he helped to found the aforementioned colony of Alliance, New Jersey.13

From Alliance, he corresponded with Leo Tolstoy and Peter Kropotkin for several years on the subject of putting their anarchist ideas into practice “in a colony of 300 souls, less than a hundred families, most of them poverty-stricken, living on poor land, and badly educated, even in farming.” Seldes saw Kropotkin’s concept of mutual aid as the guiding principal of the colony, though he had argued unsuccessfully for it to be established in Oregon where the soil was much better. The letters were destroyed some time after 1907 one winter day, when they were used by an illiterate washwoman to get a fire started in his wood stove in Pittsburgh. In 1886, he campaigned for the Single Tax leader Henry George, beginning a lifelong devotion to that radical land-reform philosophy.14

Seldes’ first wife died in 1896 and was remembered as “the kindest, most self-sacrificing, the most unselfish, and the most public-spirited person in the colony.” His sister Bertha took over raising his sons George Jr. and Gilbert, as well as running the colony’s post office from their home and serving as its midwife.15 Meanwhile George himself moved to Philadelphia and married his second wife Nunya, but he preferred that his sons be raised in a healthy country environment rather than an urban slum, and the boys remained at Alliance but visited with their father in the city. When he first arrived in the city, Seldes clerked at a drug store and studied law at night. He then saved enough money to open his own drug store at 5th and Carpenter. His son George (who became a very famous journalist), remembered this as a point where Seldes Sr. “began wasting a great part of his life selling patent medicines to ignorant strangers with whom he tried to talk Philosophy.”

“But almost every evening,” George Jr. continued in his memoir, “and late into the night, there were people in the store’s back room discussing not only Kropotkin and Tolstoy but Walt Whitman, who lived across the river in Camden, and Thoreau and Emerson, Gorki and Ibsen; and later on, Debs and American Socialism.”16

Starting in the winter and spring of 1904-05, Seldes became very involved in aiding the Russian revolutionaries who came to America to raise money for their unsuccessful revolution. Several Revolutionaries came to the city that winter and through 1906, including Catherine Breshkovskaya, Chaim Zhitlovsky, Nicholas Tchaikovsky, and Maxin Gorky. By Breshkovskaya’s third visit on March 5th, he had become President of the city’s branch of the Friends of Russian Freedom.

Seldes and the anarchist physician Simon Dubin were of the mind that the US constitution might serve as a model for a post-tsarist Russia, while other local anarchists like Chaim Weinberg and Voltairine de Cleyre felt that “if I could not wish the Russian revolutionists a better freedom than that which we have in America, I would say to them, “You had better lay down your arms.’ We wish them freedom of economic opportunities as well as constitutional liberty,” as de Cleyre put it at one event. She meant “the freedom to speak and act, not the freedom to starve in the streets,” and there was some tension between these and the more conservative members of the committee. Seldes and other anarchists received the various revolutionaries in their homes and took a major role in arranging their speaking events.17In 1905, George and Nunya Seldes gave their hospitality and organizing skills to the well-known Russian actor Paul Orlenoff and his protégé Alla Nazimoff, who performed before small audiences.18

During one of Maxim Gorky’s visits to Philadelphia in 1906, he arrived at Seldes’ drug store with his common-law wife, the actress Madame Andrayeva, after a hotel had thrown them out in reaction to the Russian Embassy’s assertion that they were committing adultery. It is not entirely clear whether they came there directly from New York or were banished from Philadelphia’s Belleview Stratford, as Seldes’ son recounted, but the drug store “was overrun with reporters interviewing Gorky.” The famous writer stayed a while, “discussing Kropotkin and the Russian soul.” During the following year, in the economic depression of 1907-08, Seldes moved to New York for a brief attempt to settle there, and then was persuaded by a relative to remove to Pittsburgh with his family, where he bought another drug store and continued his anarchist activities for the rest of his life.19

A physician who counted himself among the anarchists long after he had switched careers, was Daniel Garrison Brinton. He graduated at Yale University with an MD in 1858 and entered the Union Army in 1862 as a surgeon. He served first at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia, and then at several major Civil War battles before suffering sun stroke at Missionary Ridge (Chattanooga) in November 1863. As a result, Brinton was unable to travel through hot climates until his death.

By the early 1870, Brinton had left medicine to earn an international reputation in ethnology, though he was editor of the Medical and Surgical Reporter until 1887. During his career he wrote scores of books on aboriginal languages, literature, and religion, mostly focusing on Indians of the Americas. Unlike his successors in the field, he could not travel to the places where his subjects lived, and this fact has compromised his place in the history of ethnology in spite of his monumental achievements.

Around 1887 Brinton became active in literary societies and in the free thought movement. He attended readings by Walt Whitman, visited the old poet at his home, and lectured on Robert Browning. In 1889-90 he rallied for the erection of a statue of Giordano Bruno in Rome, and wrote a short biography of that free thought martyr.

In March 1893, Brinton was honored at a special reception by the Fellowship for Ethical Research, which was Philadelphia’s radical splinter of the Ethical Culture movement, allowing anarchist and free love subjects to be debated in its rooms. Brinton and a prominent lawyer, anti-vivisectionist and anarchist Thomas Earle White spoke at the event. On April 24, 1896, Brinton delivered a sympathetic lecture at the same club, entitled “What the Anarchists Want.”20

In 1897, Brinton tried his hand at literature. His play, Maria Candelaria: An Historical Drama From Aboriginal American Life, described a rebellion against Spanish rule in Chiapas, Mexico in 1712, which was led by the Tzental Indian queen whose name gives the title of the play. The opening lines of the first scene read as follows:

“José: What news, what news, Jacinto?

“Jacinto: Good news, José, the best of news. ‘No more priests and no more taxes, no king and no laws,’ So says she, our hamlet’s pride and glory.”21

On October 27, 1897, Brinton attended the only lecture ever delivered by Peter Kropotkin at Philadelphia. The event was held at the large and elegant Odd Fellows Temple on North Broad Street, and he was well-received by the local press. Of course, all of Philadelphia’s elites wanted to mingle with the famous anarchist sage. Kropotkin dined with his fellow scholar Daniel Brinton before the lecture, and then the anarchists of the city were invited to meet him at a private reception after the talk. This was remembered by one anarchist as “the most delightful evening perhaps of a lifetime.”22

Brinton’s health declined rapidly during the last year of his life. He died on July 31, 1899. Later that year a memorial meeting was held for Dr. Brinton, at which the keynote speaker — who had no radical credentials at all — mentioned that, “In Europe and America, he sought the society of anarchists, and mingled sometimes with the malcontents of the world that he might appreciate their grievance and weigh their propositions of reform or change.”23

The anarchist professionals of old Philadelphia demonstrated that the movement had attracted some of the brightest and most accomplished people in the city. Their participation brought the scene to a high momentum and public prestige that was remembered with longing for many decades thereafter.

Philadelphia, September 2006

——————————————————————————–

1See Roger Bruns, The Damndest Radical: The Life and World of Ben Reitman, Chicago’s Celebrated Social Reformer, Hobo King, and Whorehouse Physician (Urbana IL, 1987).

2See Paul Avrich, Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in The United States (Princeton, 1995).

3See coverage in the North American (Philadelphia), December 20-24, 1902.

4De Cleyre, “Facts and Theories,” Free Society, March 8, 1903.

5Ellen Eisenberg, Jewish Agricultural Colonies in New Jersey 1882-1920 (Syracuse NY 1995), p. 94; Philadelphia City Directories, 1889-1895. Obituaries for Gartman appeared in Jewish World, Public Ledger and Evening Bulletin (all Philadelphia) and the New York Times, on March 31, 1930.

6Judy Nicolas and Nancy J. Silberstein, “Interview with Naomi [Gartman] and Mickey Bregstein, 4 November 1991″ (courtesy NJ Silberstein). Nancy J. Silberstein is the grand-niece of Leo Gartman.

7North American, Nov. 27, 1923 p. 2; Evening Bulletin, Nov. 27, 1923 p. 3.; Directory of Deceased American Physicians, 1804-1929, entry for Bernhard Segal.

8See the Federal Census of the United States, 1900; also Goldman, Living My Life.

9See Paul Avrich, An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (Princeton, 1978), pp. 171-178.

10Death notice for Samuel H. Gordon, Evening Bulletin (Philadelphia), Nov. 11, 1906; Directory of Deceased American Physicians 1804-1929, entry for Samuel H. Gordon.

11″Miss de Cleyre, Leader of Philadelphia Anarchists, is Thrown into Jail,” North American, February 22, 1908. Bail was initially set at $2,500, but apparently lowered to $800 after argument by her lawyer, the socialist Henry John Nelson. See also reports the same day in the Evening Bulletin and Public Ledger.

12See Harry D. Boonin, The Jewish Quarter of Philadelphia: A History and Guide, (Jewish Walking Tours, 1999), p. 68; also the records of Mt. Sinai Hospital (included in a larger collection for Albert Einstein Hospital), at Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

13See Paul Avrich, The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States (Princeton, 1980), pp. 297-300; Ellen Eisenberg, Jewish Agricultural Colonies, (Syracuse, 1995), pp. 125, 142, 173.

14George H. Seldes, Tell The Truth And Run (New York, 1953). p. xxii.

15Seldes, Tell The Truth And Run. Pages xi-xxiv lovingly describe his boyhood in Alliance and visits to his father’s drug store in Philadelphia.

16Seldes, Tell The Truth And Run, p. xvii.

17″Frenzy Reigns When Anarchy’s Red Flag Breaks in on Russian Sympathy Meeting” Press (Philadelphia), March 6, 1905, p. 1.

18Seldes, Tell The Truth And Run, p. xviii.

19Seldes, Tell The Truth And Run, p. xix. News reports gave much attention to Gorky’s expulsion in New York, but Seldes Jr. states that he was expelled in Philadelphia, where we find no such reports.

20Letters, Brinton to Horace Logo Traubel, March 26 and April 27, 1896; Traubel Papers, Library of Congress.

21This and a complete set of Brinton’s books and articles are preserved at the American Philosophical Society Library, in Philadelphia.

22″Philadelphia,” Free Society, Dec. 17, 1897; see also Horace Traubel, Review of “Peter Kropotkin: A Tribute,” in Mother Earth, marking Kropotkin’s 75th Birthday, and The Conservator, 1912, page 157.

23Memorial Address by Albert H. Smyth, in “The Brinton Memorial Meeting,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, January 16, 1900.