Me gusta sentarme delante de la máquina de escribir justo cuando me despierto y ni siquiera sé quien soy, de donde vengo y hacia donde voy… cuando la mente se encuentra en una nebulosa caótica y confusa, más allá del Espacio-Tiempo y cualquier Dialéctica…

Poco a poco y mientras escribo voy “retornando” a mi yoedad (sea lo que esto sea.. ) …Abro la ventana de “mi” celda: inspiro profundamente el frío aire matutino y siento mis pulmones ensancharse… Preparo un café; su aroma me relaja; me recuerda “otro tiempo”… mi niñez y también a mi madre…

Mi madre se levantaba todos los días a las cinco de la mañana para ir a trabajar… ponía la cafetera en el hornillo de la cocina y a los pocos minutos flotaba en el aire este cotidiano aroma que tanto me gustaba… De pequeño estaba convencido que uno de los motivos por los cuales mi madre fuese tan “morena” residía en el consumo del café… no sé porqué; ocurrencias de niño…

Los fines de semana solía acompañar a mi madre al trabajo, que era cuando podía, pues no había “clases”… Me gustaba ayudar a mi madre…

Mi madre era (y es) “empleada de limpieza” y para ganarse el pan tenía que limpiar los negocios y oficinas de los otros; siempre se mostró orgullosa de su trabajo… o quizás de poder trabajar… nunca lo he sabido con exactitud…

Mi padre que era albañil (ya muerto) y construía casas para los otros, mientras nosotros vivíamos en una cuchitril alquilado, también se mostraba orgulloso de su trabajo… o quizás también de poder trabajar… tampoco lo he sabido…

Ya de pequeño comenzaba a crecer en mí un sentimiento profundo de animadversión hacia eso que hoy llamamos “trabajo asalariado”, pero que en aquel entonces se llamaba simplemente “trabajo”… De algun modo mi realidad cotidiana me estaba enseñando que quienes nada poseían debían de vender por igual su tiempo y sus fuerzas a quienes todo lo poseían…

Cuando preguntaba a mis padres porqué había pobres y ricos ellos me decían que eso siempre había sido así desde que el mundo es mundo… Siempre me chocó la “mentalidad” de mis genitores… los mendigos lo eran porque eran vagos… ; las putas eran putas porque eran viciosas… del mismo modo que los ladrones eran maleantes…

Se debía trabajar, obedecer, ser honrado y un “buen cristiano”… estar siempre dispuesto a sufrir y poner la otra mejilla… algun día, en el “más allá” encontraríamos nuestra recompensa…

Cuando era pequeño me daba verguenza decir que mi madre era “empleada de limpieza”… hoy en día siento vergüenza por haberme avergonzado de mi madre… de haberme avergonzado de haber sido pobre… (quiero decir “proletario” pues mendigar nunca hemos mendigado… ); como si haber nacido pobre, en el seno de una familia proletaria, fuese un “pecado”, algo que uno elegía…

No, no me pude acostumbrar a ese “orden de cosas”… no quise aceptar semejante orden… no quise ser un orgulloso trabajador que trabaja para “los otros” y que por dinero vende su tiempo, sus fuerzas, toda su energías y en ocasiones hasta el Alma…

(…)

Para mí la cárcel no era algo lejano y misterioso… la mitad de mi barrio habia pasado o seguía encerrado en alguna celda…

Los días de visitas (en la cárcel) miraba como a las mañanas muy temprano algunas madres, hermanas y esposas (porqué será que siempre son las mujeres las que desfilan incondicionalmente durante años en dirección a las cárceles mientras “los hombres” desaparecen y se esfuman en poco tiempo???) se dirigían con sus bolsitas de plástico llenas de alimentos y ropa rumbo a la parada del autobus que las dejaba cerca de la prisión…

Allá iban estas mujeres con la ropa limpia y los alimentos que la mayor parte de las veces compraban a “crédito” (fiado) porque en mi barrio por aquellos tiempos escaseaba el dinero y el trabajo bien remunerado; era por eso que muchos estaban precisamente en la cárcel y no porque fuesen “vagos”, “viciosas” y “maleantes”… no todos quisieron sumarse a la diaspora de la emigración (como mis padres) o el exilio… y antes que aceptar la explotación del trabajo asalariado o la dictadura del mercado postfranquista decidieron “robar” o “tomar las armas” contra todo ese orden de cosas…

Estas mujeres que compraban “fiado” y desfilaban como un ejército silencioso con sus bolsitas de plástico con destino a la cárcel, y que en muchas ocasiones se privaban de comer ellas mismas; pero que a sus hijos, hermanos y maridos su paquetito de ropa limpia y comida no podía faltarles eran la encarnación misma del amor y la solidaridad… yo amaba y sentía un enorme respeto por ellas.

Una de estas mujeres (abuela y madre) se llamaba… o la llamabamos Doña Cristina… Una viejita arrugadita de rasgos agradables y risueños … tan bajita que las bolsas de plástico que transportaba llegaban casi al suelo, haciendo que cada paso que daba semejase un esfuerzo sobrehumano… en más de una ocasión la ayudaba a transportar las bolsas hasta la parada del autobus…

Doña Cristina tenía un hijo en la cárcel desde hacia doce años… su hijo había robado algunos coches (en la época de Franco) que luego había vendido a piezas, tanto a chatarreros como mecánicos para ganar algo de dinero… Su hijo fue uno de esos (miles de… ) presos que no se beneficiaron de la “amnistía política” de finales de los setenta… su hijo era además uno de esos rebeldes organizados en la Copel (ya por entonces en declive) de los que nadie quería saber nada…

Si mi familia era “pobre”, esta familia vivía en la más absoluta de las indigencias… Las condiciones infrahumanas en las que sobrevivía esta mujer (junto a los hijos de sus hijos; y su hija; y sin “marido” o cualquier tipo de apoyo económico) me indignaron de tal modo que decidí ayudarla…

(…)

Corría el verano del 1982…

Como cada mañana se ponía en movimiento un enjambre humano que se dispersaba en todas direcciones como hormiguitas hacendosas… hileras y grupitos de hombres, mujeres y niños rumbo a sus puestos de trabajo y colegios… Era fácil descifrar por sus atuendos y uniformes sus oficios y escuelas, incluso la “clase social” a la cual pertenecían…

Eran escasos los trabajadores que acudían al trabajo con coche propio… la mayoría usaba el transporte público o se levantaban un poco mas temprano y se iban a pie…

Me encontraba sentado al volante de una Seat 131 que había robado esa misma noche en la otra punta de la ciudad… mis amigos estaban con la mirada tensa observando cada movimiento en las calles adyacentes al Banco: cada coche, cada persona, todo…

Yo observaba la empleada de limpieza que entraba a esa hora temprana al Banco: el pañuelo en la cabeza que cubría sus cabellos; los guantes de goma amarillos; un pequeño cubo de plástico donde con toda probabilidad guardaba los productos de limpieza y sus utensilios de trabajo… Me recordó a mi madre que estaría haciendo lo mismo que esta mujer sólo que en otro país… a 2.500 km de distancia…

Toni me toca en el hombro y me dice que ponga el coche en marcha, pues aquí estamos dando el cante parados delante del Banco…

Toni era conocido como “el zurdo”… años más tarde fue encontrado asesinado junto a su compañera Margot… ambos con un tiro en la cabeza; se comentaba por la calle que fue obra de la policía; de la Brigada antiatracos de Vigo…

Toni era quince años mayor que yo; tendría sobre los treinta… hacía poco que había salido de la cárcel y pertenecía a un grupo de personas que se encargaban de apoyar y difundir las luchas de los presos…

Siempre me había gustado su forma de ser… no hablaba demasiado y cuando lo hacía solía ser muy concreto…

Moure (que años más tarde se suicidó) que se encontraba sentado a mi lado en el asiento del copiloto me guiña el ojo sonriendo mientras limpiaba la grasa de las armas que tenía en su regazo…

También Moura pertenecía a este grupo de solidarios con los presos; y como Toni era mayor que yo, y había estado en la cárcel…

Nos dirigimos hacia la periferia de la ciudad ya que por allá no solía haber tanta presencia policial… al fin y al cabo a los pobres no había necesidad de “protegerlos” de su miseria… el dinero estaba en la ciudad, en los Bancos…

Una vez en el monte salimos del coche y estiramos un poco las piernas… Llevabamos toda la noche dando vueltas con el coche y estabamos cansados y con sueño…

Toni coje un palito y comienza a dibujar en el suelo las posiciones que tomaríamos y los pasos a dar durante el atraco… del mismo modo debatimos la carreteras y caminos a elegir durante la fuga, después del atraco…

En esta primera acción yo tendría que permanecer en el coche y “cubrir la retirada” en caso de que llegasen los maderos… para tal cometido Moure me entrega un rifle de repetición marca “Winchester” que me recordaba mucho a los que llevaban los “vaqueros” en las pelis de Hollywood…

Una vez aclarado todo nos metemos en el coche y vamos rumbo hacia nuestro objetivo… Cada uno de nosotros está inmerso en si mismo, es el momento donde ya no hay nada más que decirse pues todo se ha dicho con anterioridad: silencio total, concentración absoluta, una tensión difícil de describir…

Llegamos… me encuentro a unos metros del Banco… Toni me manda detener el coche…aún no había detenido el coche y veo salir a Toni como impulsado por un resorte… el pasamontaña calado y la pistola en su mano izquierda mientras grita: venga, vamos, vamos!!!

Moure le sigue unos pasos atrás, también encapuchado y armado de un revolver…

Los veo desaparecer en el interior del Banco… algunos transeuntes quedan estupefactos viendo estas escenas; miran para el Banco y miran hacia mi dirección…

No sé exactamente que se supone debo hacer con los “mirones”, pero para quitarme el nerviosismo que tengo decido bajar del coche y hacer algo… agarro el rifle y les suelto algo asi como: venga cabrones, largaos antes de que me lie a a tiros!!!

Yo estoy con la cara descubierta… tan solo unas gafas de sol cubren un poco mi rostro. Por suerte no fue necesario repetir las amenazas; los espectadores se retiran del escenario… Me quedo fuera del coche mirando hacia el Banco y apuntando con el rifle hacia las calles por donde pueden aparecer los esbirros… mi corazón golpea furioso en el pecho; tengo ganas de mi inhalador de asma pero recuerdo que lo olvidé en casa… me sudan las manos… los minutos se hacen eternos… si aparece la madera estoy dispuesto a disparar… eso es lo que hemos acordado… me digo a mi mismo que la próxima vez yo no me quedo en el coche… prefiero entrar en el Banco… al fin veo salir del Banco a mis amigos que vienen corriendo en dirección al coche… salto dentro, echo el rifle en el asiento trasero y los recojo…

En el coche se libera toda la energía y tensión acumuladas en los momentos precedentes… Mis amigos se rien; yo también… hacen bromas sobre mi aspecto con el rifle y las gafas de sol… vamos a toda velocidad por la ruta que habíamos previsto con anterioridad… los dejo en el punto convenido donde se ponen a salvo ellos, las armas y el dinero… yo tengo que deshacerme del coche lejos de nuestra “base”… tengo por costumbre quemar los coches…

Unos días mas tarde la señora Cristina encuentra en la puerta de su casa una bolsa con 150.000 pesetas de la época… En el barrio aparecen pintadas con una pintura roja: Amnistía total!!! Todos los presos a la calle!

Los izquierdistas del barrio hablan de los “presos políticos”… la gente del barrio no les entienden… al fin y al cabo los “presos políticos” ya fueron liberados en dos amnistías parciales…hablan de “solidaridad”, de “libertad”, de… pero solo para los presos de sus organizaciones… y los presos del barrio?

Yo no asisto a las reuniones “políticas”… tengo 15 años y no entiendo lo que dicen… además siempre hablan los mismos… hablan como “los tipos de la televisión”…

Me despido con un abrazo de mis amigos… tienen reunión… yo estoy planeando robar un almacen de productos alimenticios (Revilla) para repartir la comida por el barrio… lo que lograré coronar con éxito…

– Llamarme cuando planeéis otra accion… la política no me interesa…

Durante más de dos años logramos expropiar con éxito mas de veinte sucursales bancarias, una docena de gasolineras y otras acciones del género…

(…)

Ya han transcurrido casi 30 años de estas escenas, de estas cosas, de estos “discursos”; y, sin embargo, parece ser un tema “actual” esto de diferenciar a los presos…

Es absurdo considerar que solo los presos con conciencia política son dignos de nuestra “solidaridad”… como si los hijos de la señora Cristina no fuesen también resultado de la prepotencia del sistema… como si los “lumpen” fuesen incapaces de extraer conclusiones sobre sus experiencias y condiciones… como si su falta de “instrucción” y “cultura”; de dinero y apoyos no fuesen de por sí suficiente castigo y ostracismo…

Estas diferencias en la cárcel no sirven para nada, no son relevantes porque la arquitectura carcelaria se encarga de “mezclar” a los presos no en base a su “ideología política” sino a todo lo contrario… el tiempo, la arquitectura, “el personal”, las condiciones, la mentalidad, los individuos… todo está construido artificialmente… construido de tal modo que las relaciones de poder y fuerza son la consecuencia del “funcionamiento cotidiano” es decir: la alienación, la prepotencia, etc…

Como mecanismo de defensa (o mejor autodefensa) tanto dentro como fuera (el Sistema es el mismo a uno y otro lado del muro) de estas falsas “separaciones” (compartimentaciones) es la organizacion informal… y esta no se basa “solo” para y con las acciones; sino que toda actividad responde a una “organización de tareas” que persiguen dos fines simultáneos, a decir: “vivir nuestra vida, hoy y ahora”; y no obstante marcarse fines mas “ambiciosos” que “transciendan” nuestra propia “individualidad” y que tampoco significa enanejar o alienar al individuo en aras de no se sabe bien que tipo de “comunidad” o “comunismo”…

Aquello que deseamos… o al menos yo lo deseo… es que desasparezcan las relaciones de poder, basadas en la fuerza… que se viva y actue tal y como nos lo dictan “las entrañas”… que veamos a “los demás” no como “objetos” y/o “sujetos” sino como individuos…

La libertad no consiste en “alienar” al otro sino en comprender aquellos “intereses” y deseos que compartimos juntos en aras de la libertad común… y, en este sentido, vivir/organizarse y actuar/pensar en común sin “renunciar” a si mismo… sin delegar, participando, manchandose las manos, implicandose, aceptando “responsabilidades”, etc., etc…

No existe una sola organización que esté por encima de mi libertad individual… y tampoco quiero formar parte de una revolución en la que no se pueda bailar.

=================================================

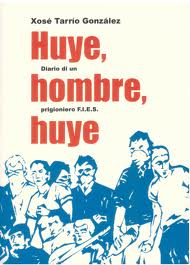

Gabriel Pombo Da Silva: Introduction to the French Edition of Xosé Tarrío González’ Huye, Hombre, Huye

I like to sit down in front of the typewriter just as I’m waking up, when I still don’t know who I am, where I come from, or where I’m going. My head is in the clouds, hazy and chaotic, beyond Space-Time or any Dialectic.

While I write, my sense of self (whatever that may be) gradually “returns.” I open “my” cell window, take a deep breath of the cold morning air, and feel my lungs expand. I make coffee, and its aroma relaxes me, reminding me of “another time”—my childhood—as well as my mother.

My mother woke up every day at 5 a.m. to go to work. She would put the coffeepot on the kitchen stove, and in a few minutes that familiar aroma I found so appealing was wafting through the air. When I was little, I was convinced that one of the reasons my mother was so “dark” was because of all the coffee she drank. Who knows why? Kids have crazy ideas.

On weekends, “class” wasn’t in session, so I was usually able to go to work with my mother. I enjoyed helping her.

My mother was (and is) a “cleaning worker,” and to earn a living she had to clean other people’s shops and offices. She always took pride in her work. Or perhaps it just was pride in having a job. I never knew exactly which.

My father (now dead) was a construction worker, and he built houses for other people while we lived in a rented shithole. He also took pride in his work. Or perhaps it was also just pride in having a job. Again, I didn’t know which.

Even as a child, a deep feeling of hostility was beginning to grow within me toward what we now call “wage-labor,” but what was simply called “work” back then. Somehow, my daily reality was teaching me that those who had nothing were being forced to sell their time as well as their energy to whose who had everything.

When I asked my parents why there were poor people and rich people, they told me it had always been that way since the beginning of time. My parents’ “mentality” always shocked me: beggars were beggars because they were lazy, whores where whores because they were depraved, thieves were thieves because they were evil.

You had to work, obey, be honest, and be a “good Christian,” always willing to suffer and turn the other cheek. Someday, in the “great beyond,” we would find our reward.

When I was a child, I was embarrassed to say that my mother was a “cleaning worker.” Now, I feel embarrassed for having been ashamed of my mother, for having been ashamed of being poor (I mean “proletarian,” since we never had to go begging)—as if having been born poor, in the heart of a proletarian family, was a “sin” or something you chose.

No, I couldn’t get used to that “order of things.” I didn’t want to accept such an order. I didn’t want to be a proud worker who worked for “other people” and sold his time, his strength, all his energy, and sometimes even his Soul for money. . . .

To me, prison wasn’t anything distant or mysterious. Half the people in my neighborhood had been or were currently locked up in some cell.

Very early in the morning on (prison) visiting days, I would watch mothers, sisters, and wives (why are women always the ones who unconditionally make trips to prison year after year, while it’s the “men” who disappear into thin air after no time at all?) set off with their little plastic bags full of food and clothing to wait for the bus that would drop them off near the prison.

Off those women went, with clean clothes and food that were often bought on “account” (credit), because in those days money and well-paid work were in short supply in my neighborhood. That’s exactly why so many people were in prison. It had nothing to do with being “lazy,” “depraved,” or “evil.” Not everyone wanted to join the diaspora of immigration (like my parents did) or exile, so instead of accepting the exploitation of wage-labor or the dictatorship of the post-Franco market, they decided to “steal” or “take up arms” against that entire order of things.

Those women who bought on “credit” and marched with their little plastic bags like a silent army toward prison, often depriving themselves of food so that their sons, brothers, and husbands would never have to do without their little package of food and clean clothes, were the very embodiment of love and solidarity. I felt tremendous love and respect for them.

One of those women (she was both a mother and a grandmother) was called, or rather we called her, Doña Cristina. She was a little old wrinkled lady with a kind, cheerful personality, but so tiny that the plastic bags she carried almost touched the ground, making each step she took seem like a superhuman effort. On more than one occasion I helped carry her bags to the bus stop.

Doña Cristina’s son had been in prison for 12 years. He had stolen several cars (during the Franco era) that he later sold for parts to scrap yards and repair shops in order to make some money. He was one of those (thousands of) prisoners who didn’t benefit from the “political amnesty” at the end of the 1970s. He was also one of the rebels who organized the Committee of Prisoners in Struggle (COPEL, which was already in decline by then), and no one wanted anything to do with them.

If my family was “poor,” then Doña Cristina’s family lived in the most abject destitution. The subhuman conditions in which that woman survived (together with her daughter and her children’s children, and without a “husband” or any kind of economic support) infuriated me so much that I decided to help her out. . . .

It was the summer of 1982.

Like every morning, a swarm of human beings was set in motion. They spread out in all directions like tiny worker ants—little rows and groups of men, women, and children on the way to their workplaces and schools. From their outfits and uniforms, it was easy to figure out their job, schooling, and even the “social class” they belonged to.

Few workers went to work in their own cars. Most of them used public transportation or woke up a little earlier and went on foot.

I was sitting at the wheel of a Seat 131 I’d stolen that very night from another part of the city. My friends’ faces were tense, observing every movement on the streets adjacent to the Bank—every car, every person, everything.

I watched a cleaning worker enter the Bank at this early hour: the headscarf covering her hair, the yellow rubber gloves, the little plastic bucket that probably held cleaning products and supplies. I was reminded of my mother, who was doing exactly the same thing as this woman, but in another country 2,500 kilometers away.

Toni tapped my shoulder and told me to move the car. Here, parked right in front of the Bank, we were drawing too much attention to ourselves.

Toni was known as “Lefty.” Years later he was found murdered alongside his girlfriend Margot. Both of them had been shot in the head. Word on the street was that it was the work of the Vigo police department’s Robbery Squad.

Toni was 15 years older than me, so he must have been around 30 at the time. He had just recently been released from prison and was part of a group that was responsible for supporting and disseminating the struggle of prisoners.

I always liked his demeanor. He didn’t talk too much, and when he did speak, he was usually very specific.

Moure (who committed suicide years later) was sitting next to me in the passenger’s seat. He winked at me, smiling while he cleaned the oil off the weapons he had in his lap.

Moure also belonged to the prisoner solidarity group. Like Toni, he was older than me and had been in prison.

We drove to the outskirts of the city since there usually wasn’t any police presence there. After all, the poor didn’t need to be “protected” from their misery. The money was downtown, in the Banks.

Once we were out in the sticks, we got out of the car to stretch our legs a bit. We’d spent the whole night driving around, and we were tired and needed sleep.

Toni picked up a twig. In the dirt, he began to sketch out the positions we would take up and the steps we would follow during the robbery. We also discussed the roads and routes we would use for our escape after the robbery.

During this first action, I would have to remain in the car and “cover our withdrawal” in case the pigs showed up. For the task, Moure handed me a Winchester repeating rifle that very much reminded me of the ones “cowboys” carried in Hollywood movies.

Once everything was sorted out, we got back in the car and headed for our target. Each one of us was immersed in himself. At such moments, there is nothing left to say. Everything has already been said. All that remains is total silence, complete concentration, and indescribable tension.

We arrived. When we were a few meters from the Bank, Toni told me to stop the car, but we hadn’t yet come to a full stop when I saw him leap out as if propelled from a slingshot. With a ski mask covering his face and a pistol in his left hand, he shouted: “Come on, let’s go, let’s go!”

Moure followed a few steps behind, also masked and armed with a revolver.

I saw them disappear into the Bank. Some pedestrians were dumbstruck by the whole scene. They were staring at the Bank, and then they looked in my direction.

I didn’t know exactly what I was supposed to do with these “spectators,” but to calm my nerves I decided to get out of the car and do something. I grabbed the rifle and approached them, saying something like: “Move along assholes! Get out of here before I start shooting!”

I wasn’t wearing a ski mask, and the only thing partially covering my face was a pair of sunglasses. Luckily, it wasn’t necessary to repeat my threats. The spectators left the scene. I remained outside the car, watching the Bank with my rifle pointed down the street in case the pigs showed up. My heart was beating furiously in my chest. I reached for my asthma inhaler, then remembered that I had left it at home. My hands were sweating. Each minute became an eternity. If the pigs appeared, I was prepared to shoot. That’s what we had agreed to. I told myself that next time I wasn’t going to stay in the car. It was better to be inside the Bank. Finally, I saw my friends exit the Bank and come running in the direction of the car. I jumped in, threw the rifle in the back seat, and picked them up.

In the car, all the tension and energy that had built up during the robbery was released. My friends were all smiles, and so was I. They joked about how I looked with the rifle and sunglasses. We took the prearranged route at top speed, and I left them at a spot we had chosen in advance, where they hid themselves, the weapons, and the money. I had to get rid of the car far away from our “base,” and I usually torched the cars we used.

A few days later, Doña Cristina found a bag full of 150,000 pesetas on her doorstep. Around the neighborhood, graffiti appeared in red paint: Total amnesty! All prisoners to the streets!

The neighborhood leftists talked about “political prisoners,” but people in the neighborhood didn’t understand them. After all, the “political prisoners” had already been released thanks to two partial amnesties. They talked about “solidarity,” about “freedom,” but only for prisoners from their organizations. What about the prisoners from the neighborhood?

I didn’t attend “political” meetings. I was 15 years old and didn’t understand what the people there were saying. Also, it was always the same ones who spoke. They talked like “television personalities.”

I said goodbye to my friends with an embrace. They had a meeting to go to. I was planning to rob a food warehouse in Revilla and then distribute the food throughout the neighborhood. It was an action I managed to pull off successfully.

“Call me when you’re planning another action. I’m just not interested in politics.”

Over the course of two years, we managed to successfully expropriate over 20 bank branches and a dozen gas stations, along with other actions of that type. . . .

Almost 30 years have now gone by since those events, those times, those “speeches,” yet differentiating between prisoners still seems to be “topical.”

It’s absurd to think that only prisoners with political consciousness are worthy of our “solidarity.” As if Doña Cristina’s son wasn’t also a result of the system’s contempt. As if the “lumpen” were incapable of drawing conclusions from their own experiences and circumstances. As if their lack of “education” and “culture,” of money and support, wasn’t punishing and ostracizing enough in itself.

In prison, those differences are meaningless and irrelevant, because the architecture of prison doesn’t “mix” prisoners according to their “political ideology.” It’s quite the opposite. Time, architecture, “employees,” conditions, attitudes, and individualities are all artificially constructed in such a way that the “day-to-day operations” produce relationships of power and coercion—in other words, alienation, contempt, etc.

One defense mechanism (or even better, self-defense) against these false “dichotomies” (compartmentalizations), inside as well as outside (the System is the same on both sides of the walls), is informal organization based not only on action, but on any activity in accordance with a “distribution of tasks” that pursues two simultaneous ends: “living our lives in the here and now,” but also defining more “ambitious” goals that “transcend” our own “individuality” without dehumanizing or alienating anyone in the name of some hypothetical “community” or “communism.”

What we want, or at least what I want, is the disappearance of power relations based on coercion: to live and act according to the principles of our hearts, to see “others” not as “objects” and/or “subjects” but as individuals.

Freedom doesn’t mean “alienating” ourselves. It means understanding our common “interests” and desires in pursuit of a shared liberty, and in that sense living/organizing and acting/thinking in concert without having to “sacrifice” oneself to delegation, participation, dirtying one’s hands, getting involved, accepting “responsibilities,” etc.

No single organization takes precedence over my individual liberty, and I don’t want to be part of any revolution that doesn’t let me dance.