Alexander Berkman

Modern philanthropy has added a new role to the repertoire of penal institutions. While, formerly, the alleged necessity of prisons rested, solely, upon their penal and protective character, to-day a new function, claiming primary importance, has become embodied in these institutions — that of reformation.

Hence, three objects — reformative, penal, and protective — are now sought to be accomplished by means of enforced physical restraint, by incarceration of a more or less solitary character, for a specific, or more or less indefinite period.

Seeking to promote its own safety, society debars certain elements, called criminals, from participation in social life, by means of imprisonment. This temporary isolation of the offender exhausts the protective role of prisons. Entirely negative in character, does this protection benefit society? Does it protect?

Let us study some of its results.

First, let us investigate the penal and reformative phases of the prison question.

Punishment, as a social institution, has its origin in two sources; first, in the assumption that man is a free moral agent and, consequently, responsible for his demeanor, so far as he is supposed to be compos mentis; and, second, in the spirit of revenge, the retaliation of injury. Waiving, for the present, the debatable question as to man’s free agency, let us analyze the second source.

The spirit of revenge is a purely animal proclivity, primarily manifesting itself where comparative physical development is combined with a certain degree of intelligence. Primitive man is compelled, by the conditions of his environment, to take the law into his own hands, so to speak, in furtherance of his instinctive desire of self-assertion, or protection, in coping with the animal or human aggressor, who is wont to injure or jeopardize his person or his interests. This proclivity, born of the instinct of self-preservation and developed in the battle for existence and supremacy, has become, with uncivilized man, a second instinct, almost as potent in its vitality as the source it primarily developed from, and occasionally even transcending the same in its ferocity and conquering, for the moment, the dictates of self-preservation.

Even animals possess the spirit of revenge. The ingenious methods frequently adopted by elephants in captivity, in avenging themselves upon some particularly hectoring spectator, are well known. Dogs and various other animals also often manifest the spirit of revenge. But it is with man, at certain stages of his intellectual development, that the spirit of revenge reaches its most pronounced character. Among barbaric and semi-civilized races the practice of personally avenging one’s wrongs — actual or imaginary — plays an all-important role in the life of the individual. With them, revenge is a most vital matter, often attaining the character of religious fanaticism, the holy duty of avenging a particularly flagrant injury descending from father to son, from generation to generation, until the insult is extirpated with the blood of the offender or of his progeny. Whole tribes have often combined in assisting one of their members to avenge the death of a relative upon a hostile neighbor, and it is always the special privilege of the wronged to give the death-blow to the offender.

Even in certain European countries the old spirit of blood-revenge is still very strong. The semi-barbarians of the Caucasus, the ignorant peasants of Southern Italy, of Corsica and Sicily, still practice this form of personal vengeance; some of them, as the Tsherkessy, for instance, quite openly; others, as the Corsicans, seeking safety in secrecy. Even in our so-called enlightened countries the spirit of personal revenge, of sworn, eternal enmity, still exists. What are the secret organizations of the Mafia type, so common in all South European lands, but the manifestations of this spirit?! And what is the underlying principle of duelling in its various forms — from the armed combat to the fistic encounter — but this spirit of direct vengeance, the desire to personally avenge an insult or an injury, fancied or real; to wipe out the same, even with the blood of the antagonist. It is this spirit that actuates the enraged husband in attempting the life of the “robber of his honor and happiness.” It is this spirit that is at the bottom of all lynch-law atrocities, the frenzied mob seeking to avenge the bereaved parent, the young widow or the outraged child.

Social progress, however, tends to check and eliminate the practice of direct, personal revenge. In so-called civilized communities the individual does not, as a rule, personally avenge his wrongs. He has delegated his “rights” in that direction to the State, the government; and it is one of the “duties” of the latter to avenge the wrongs of its citizens by punishing the guilty parties. Thus we see that punishment, as a social institution, is but another form of revenge, with the State in the role of the sole legal avenger of the collective citizen — the same well-defined spirit of barbarism in disguise. The penal powers of the State rest, theoretically, on the principle that, in organized society, “an injury to one is the concern of all”; in the wronged citizen society as a whole is attacked. The culprit must be punished in order to avenge outraged society, that “the majesty of the Law be vindicated.” The principle that the punishment must be adequate to the crime still further proves the real character of the institution of punishment: it reveals the Old-Testamental spirit of “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” — a spirit still alive in almost all so-called civilized countries, as witness capital punishment: a life for a life. The “criminal” is not punished for his offence, as such, but rather according to the nature, circumstances and character of the same, as viewed by society; in other words, the penalty is of a nature calculated to balance the intensity of the local spirit of revenge, aroused by the particular offence.

This, then, is the nature of punishment. Yet, strange to say — or naturally, perhaps — the results attained by penal institutions are the very opposite of the ends sought. The modern form of “civilized” revenge kills, figuratively speaking, the enemy of the individual citizen, but breeds in his place the enemy of society. The prisoner of the State no longer regards the person he injured as his particular enemy, as the barbarian does, fearing the wrath and revenge of the wronged one. Instead, he looks upon the State as his direct punisher; in the representatives of the law he sees his personal enemies. He nurtures his wrath, and wild thoughts of revenge fill his mind. His hate toward the persons, directly responsible, in his estimation, for his misfortune — the arresting officer, the jailer, the prosecuting attorney, judge and jury — gradually widens in scope, and the poor unfortunate becomes an enemy of society as a whole. Thus, while the penal institutions on the one hand protect society from the prisoner so long as he remains one, they cultivate, on the other hand, the germs of social hatred and enmity.

Deprived of his liberty, his rights, and the enjoyment of life; all his natural impulses, good and bad alike, suppressed; subjected to indignities and disciplined by harsh and often inhumanely severe methods, and generally maltreated and abused by official brutes whom he despises and hates, the young prisoner, utterly miserable, comes to curse the fact of his birth, the woman that bore him, and all those responsible, in his eyes, for his misery. He is brutalized by the treatment he receives and by the revolting sights he is forced to witness in prison. What manhood he may have possessed is soon eradicated by the “discipline.” His impotent rage and bitterness are turned into hatred toward everything and everybody, growing in intensity as the years of misery come and go. He broods over his troubles and the desire to revenge himself grows in intensity, his until then perhaps undefined inclinations are turned into strong anti-social desires, which gradually become a fixed determination. Society had made him an outcast; it is his natural enemy. Nobody had shown him either kindness or mercy; he will be merciless to the world.

Then he is released. His former friends spurn him; he is no more recognized by his acquaintances; society points its finger at the ex-convict; he is looked upon with scorn, derision, and disgust; he is distrusted and abused. He has no money, and there is no charity for the “moral leper.” He finds himself a social Ishmael, with everybody’s hand turned against him — and he turns his hand against everybody else.

The penal and protective functions of prisons thus defeat their own ends. Their work is not merely unprofitable, it is worse than useless; it is positively and absolutely detrimental to the best interests of society.

It is no better with the reformative phase of penal institutions. The penal character of all prisons — workhouses, penitentiaries, state prisons — excludes all possibility of a reformative nature. The promiscuous mingling of prisoners in the same institution, without regard to the relative criminality of the inmates, converts prisons into veritable schools of crime and immorality.

The same is true of reformatories. These institutions, specifically designed to reform, do as a rule produce the vilest degeneration. The reason is obvious. Reformatories, the same as ordinary prisons, use physical restraint and are purely penal institutions — the very idea of punishment precludes true reformation. Reformation that does not emanate from the voluntary impulse of the inmate, one which is the result of fear — the fear of consequences and of probable punishment — is no real reformation; it lacks the very essentials of the latter, and so soon as the fear has been conquered, or temporarily emancipated from, the influence of the pseudo-reformation will vanish like smoke. Kindness alone is truly reformative, but this quality is an unknown quantity in the treatment of prisoners, both young and old.

Some time ago I read the account of a boy, thirteen years old, who had been confined in chains, night and day for three consecutive weeks, his particular offence being the terrible crime of an attempted escape from the Westchester, N. Y., Home for Indigent Children (Weeks case, Superintendent Pierce, Christmas, 1895). That was by no means an exceptional instance in that institution. Nor is the penal character of the latter exceptional. There is not a single prison or reformatory in the United States where either flogging and clubbing, or the straight-jacket, solitary confinement, and “reduced” diet (semi-starvation) are not practiced upon the unfortunate inmates. And though reformatories do not, as a rule, use the “means of persuasion” of the notorious Brockway, of Elmira, N. Y., yet flogging is practiced in some, and starvation and the dungeon are a permanent institution in all of them.

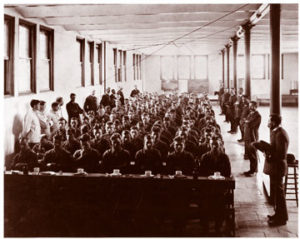

Aside from the penal character of reformatories and the derogatory influence the deprivation of liberty and enjoyment exercise on the youthful mind, the associations in those institutions preclude, in the majority of cases, all reformation. Even in the reformatories no attempt is made to classify the inmates according to the comparative gravity of their offenses, necessitating different modes of treatment and suitable companionship. In the so-called reform schools and reformatories children of all ages — from 5 to 25 — are kept in the same institution, congregated for the several purposes of labor, learning and religious service, and allowed to mingle on the playing grounds and associate in the dormitories. The inmates are often classified according to age or stature, but no attention is paid to their relative depravity. The absurdity of such methods is simply astounding. Pause and consider. The youthful culprit who is such probably chiefly in consequence of bad associations, is put among the choicest assortment of viciousness and is expected to reform! And the fathers and mothers of the nation calmly look on, and either directly further this species of insanity or by their silence approve and encourage the State’s work of breeding criminals. But such is human nature — we swear it is day-time, though it be pitch-dark; the old spirit of credo quia absurdum est.

It is unnecessary, however, to enlarge further upon the debasing influence those steeped in crime exert over their more innocent companions. Nor is it necessary to discuss further the reformative claims of reformatories. The fact that fully 60 per cent of the male prison population of the United States are graduates of “Reformatories” conclusively proves the reformative pretentions of the latter absolutely groundless. The rare cases of youthful prisoners having really reformed are in no sense due to the “beneficial” influence of imprisonment and of penal restraint, but rather to the innate powers of the individual himself.

Doubtless there exists no other institution among the diversified “achievements” of modern society, which, while assuming a most important role in the destinies of mankind, has proven a more reprehensible failure in point of attainment than the penal institutions. Millions of dollars are annually expended throughout the “civilized” world for the maintenance of these institutions, and notwithstanding each successive year witnesses additional appropriations for their improvement, yet the results tend to retrogade rather than advance the purports of their founding.

The money annually expended for the maintenance of prisons could be invested, with as much profit and less injury, in government bonds of the planet Mars, or sunk in the Atlantic. No amount of punishment can obviate crime, so long as prevailing conditions, in and out of prison, drive men to it.

Mother Earth 1, no. 6 (August 1906): 23–29.