As millions of refugees brave their way across a Europe increasingly hostile to their existence, it is still Syrians dominating the headlines. But the third-largest group crossing the Mediterranean is fleeing the small African country Eritrea, home to one of the most corrupt and brutal regimes in the world.

The gut-wrenching photo of drowned toddler Alan Kurdi has strained Canadians’ humanitarian mettle. Many have criticized Stephen Harper’s failure to welcome a single refugee across Canada’s borders since publication of the photo, yet few have reckoned with the ways in which Canadians are complicit in driving desperate people toward the sea.

Earlier this month, Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson hosted a public forum on the refugee crisis. Those in attendance discussed the complexity and cost of privately sponsoring refugees and revisited a campaign promise to make Vancouver a Sanctuary City.

Daniel Tseghay, a writer, broadcaster and an activist, is of Eritrean descent and spoke at the mayor’s forum. “Every single Eritrean that exists in the diaspora,” Tseghay told Mayor Robertson, “knows someone directly or has someone in their family who has drowned in the Mediterranean.”

While the initiatives proposed by the city are wonderful and should be supported, he added, “there’s also a lot we can do to prevent people from becoming refugees in the first place.”

Tseghay cited Nevsun Resources, a mid-tier mining corporation headquartered a few doors down from the Georgia Hotel in downtown Vancouver. Nevsun owns and operates one of the biggest open-pit copper mines in the world, the Bisha Mine in Eritrea. The mine providesnearly one-third of Eritrea’s foreign exchange earnings.

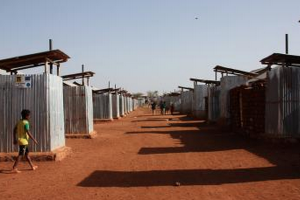

Last November, three Eritrean refugees filed a civil suit against the company in the B.C. Supreme Court for alleged slave labour practices in its camps. The suit alleges that as many as 600 military conscripts were forced to build the Bisha mine in the first stage of its construction. Nevsun vigorously denies the charges — even though in 2013, it was pressured to admit “regret” that Segen, the government subcontractor all foreign investors are forced to use, had exploited conscripts from the Eritrean army.

“People are fleeing Eritrea for a number of reasons,” Tseghay told rabble.ca. “But at the forefront of people’s minds for leaving Eritrea is the threat of being conscripted indefinitely.”

This June a damning United Nations report that specifically names Nevsun and the Bisha mine found that Eritrea was guilty of widespread human rights abuses including extrajudicial murder, widespread torture, rape and forced labour.

“Vancouver is pretty directly involved in exacerbating, in fuelling this refugee crisis in Eritrea,” Tseghay said. When Eritreans flee their homeland, he adds, they are fleeing a Canadian mining company.

Vancouver is a mining superpower. Approximately 800 mineral exploration and extraction corporations call the city home. Canada has one of the lowest corporate tax rates in the world and the extraction industry enjoys massive backing from the Harper government. There are no mechanisms in place to sanction Nevsun and no statement of condemnation from the relevant ministry — even though the House of Commons International Development’s Subcommittee on International Human Rights has been holding hearings on Nevsun’s operations since February 2012.

Last week, Sunridge Gold Corp., another Vancouver-based resource firm, announced it had been awarded three mining licenses in Eritrea to build a copper, zinc and gold mine worth billions. Shares in Sunridge rose 12 per cent before lunchtime.

“When the city focuses on some of the things it can do to offer space for the current refugees without discussing its own complicity in a system that makes it wealthy,” Tseghay said, “I feel like it is a form of saviourism.”

“Let’s not discuss the ways in which we’ve created this problem,” said Tseghay. “Let’s only look at the grand and noble and laudable ways in which we’ve helped these ‘poor’ people. That’s how it comes off and I think that is a major problem.”

“It gives the city a reputation it doesn’t deserve.”

The vast majority of Eritrean refugees, about 90 per cent, are between the ages of 18 and 24 years old. But even UN officials have been shocked by the high numbers of children under the age of eight fleeing Eritrea for Europe without a parent or guardian. Last year, the number of Eritrean refugees arriving in Europe tripled to 37,000 — and 78 unaccompanied minors arrived in a single month.

In April, two boats heading to Italy from Libya capsized within a single week and over 1,300 refugees, including countless Eritreans, perished.

The death of three-year-old Alan Kurdi finally touched a nerve here in Canada, spurring many to finally take seriously a refugee crisis at least four years in the making.

There has been no viral photo of a black Eritrean child that has impelled wealthier nations into action. No western country has vowed to immediately redraw its inadequate refugee policy because hundreds of black and brown bodies were claimed by the Mediterranean.

“We know that there’s this history of African children, of their pain being neglected or their pain being diminished and not seen as extreme or as requiring as much attention as the pain of a light-skinned child,” says Tseghay. “That’s a real phenomenon.”

“I’m glad that there has been the response and the attention drawn to the refugee crisis because of that photo,” says Tseghay. “But it is disheartening that we didn’t see that same response [to] photos of little black children.”

“Black death, African death is unimportant. It’s seen as natural and as something that we shouldn’t really worry too much about.”

Last week, Nevsun announced it would be expanding its drilling in the Harena region of the Bisha mine while the refugee crisis continues apace. Nevsun did not respond to requests for comment.