Ernest Coeurderoy – Citizen of the World

One selection I really regret not including in Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas is the following piece by Ernest Cœurderoy (1825-1862), excerpted from his Jours d’exil (Paris: P.-V. Stock, 1910-11, originally published 1854-55) and translated by Paul Sharkey. Coeurderoy is perhaps best known for his Hurrah!!! Ou La Révolution par les Cosaques (London, 1854; republished by Editions Plasma, Paris, 1977), in which he envisioned a Cossack invasion of France to sweep away all vestiges of authority, with a libertarian socialist society emerging from the ruins.

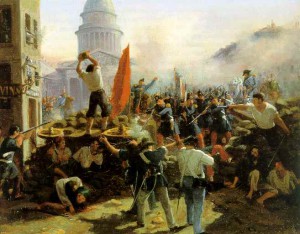

Coeurderoy was a radical republican turned socialist active in the 1848 Revolution in France. Trained as a doctor, he cared for injured workers following the abortive uprising of June 1848. He opposed the rise to power of Napoleon III and was forced into exile, first in Switzerland and later in England. In this excerpt from Jours d’exil (Days of Exile), Coeurderoy identifies himself with the outcast, the disadvantaged and forsaken in society, in a manner reminiscent of the much more recent and better known self-description of Subcomandante Marcos from the modern Zapatista movement in Mexico: “Marcos is gay in San Francisco, black in South Africa, an Asian in Europe, a Chicano in San Ysidro, an anarchist in Spain, a Palestinian in Israel, a Mayan Indian in the streets of San Cristobal, a Jew in Germany, a Gypsy in Poland, a Mohawk in Quebec, a pacifist in Bosnia, a single woman on the Metro at 10:00 P.M., a peasant without land, a gang member in the slums, an unemployed worker, an unhappy student and, of course, a Zapatista in the mountains.”

I am a citizen of the world these days and regard that title as greater than anything the proudest of nations can bestow; what is more, it is of my own choosing and not doled out through some accident of birth. I am exiled, which is to say, free; these days one can only be so outside of society, country and family, all of them buckling under shameful servitude. What care I about armies, flags, governments and police! I skip across frontiers like the smuggler. I have no home, no land for which I am required to pay tax. Far from me, kings ascend their thrones and step down from them like shame-faced crooks; and I laugh at this phantasmagoria. I flee from churches the way I would from the gates of Hell. Laws are not made for me; I am outside the law and prefer that to being under its protection. I am a vagabond; and, first and foremost, revel in the fact. Neither king nor subject: the strong are stronger on their own.

In every land there are folk who are kicked out and driven away, killed and burnt out without a single voice of compassion to speak up for them. They are the Jews. – I am a Jew.

Skinny, untamed, restless men, sprightlier than horses and as dusky as the bastards of Shem, roam through the Andalusian countryside. Real wolves. They give every appearance of being horse-traders, but nobody is quite sure what trade they ply and the common gossip accuses them of sorcery. They are not – lucky mortals! – deemed worthy of being subjected to the laws of Spain. They live and marry according to their own ways. They drift through civilization, setting up their tents on the forest’s edge. The doors of every home are barred to them, in hamlet and town alike. A widespread disapproval weighs upon their breed; no one knows whence it comes nor whither it is bound. Such men are known as Gitanos. – I am a Gitano.

In the mountains of Scotland and Norway, out on the heaths of England and Ireland, camp sorcerer clans that have provided inspiration for the divine voices of Shakespeare and Walter Scott. They dance in the mist, setting huge fires of holly and gorse ablaze and, come nightfall, under the pale moonlight they summon up the spirits from the abyss. They go by the name Gypsies. – I am a Gypsy.

In Paris one can see wayward boys, naked, who hide under the bridges along the canal in the mid-winter and dive into the murky waters in search of a sou tossed to them by a passing onlooker. They go unshod upon the asphalt of the quays and boulevards and have nowhere to shelter other than under the lee of the roofs and carriage entrances. Their trade consists in purloining scarves and pretending to ask for a light but swapping cigarettes. These are the Bohemians. – I am a Bohemian.

In Naples the Lazzaroni sprawl on the marble terraces of the ducal palaces, rubbing their bellies in the sunshine while dining on a glass of water and a quattrino of macaroni. – I am a Lazzarone.

In Switzerland and Germany one sees folk with neither creed nor law, rights nor duties and whose origins no one knows and who seem lost among all the rest. They are known as the Heimatlosen. I am a Heimatslos.

Ah, if only I, like all the homeless folk, could spend my days in the shaded woodland and my nights under the beautiful stars, on the flowering banks of the streams! But I was raised in comfort, like the grocer’s children.

Everywhere, there are folk banned from promenades, museums, cafes and theatres because a heartless wretchedness mocks their day wear. If they dare to show themselves in public, every eye turns to stare at them; and the police forbid them to go near fashionable locations. But, mightier than any police, their righteous pride in themselves takes exception to being singled out for widespread stigma. – I am one of that breed.

Oh the bourgeois misery, somber as any Whitechapel proletarian, wretchedness in greasy and down-at-heel boots, a wretchedness that wears a long neck-tie and an excuse for a shirt and which never laughs and dares not weep! Hypocritical, indescribable, unutterable, unclassifiable, hope-destroying misery, the greatest, most atrocious of all miseries! The misery of a study supervisor!

There are young folk everywhere, shunned by everyone else because they are the outcasts of society, because they are not acceptable and will not abide by the world’s conventions. They are stiff-backed and angular types; they have a look of gloom about them; the buzz of conversation irritates them. They love broad ideas and loose clothing; their thoughts are bad and their status worse. They dare to question the infallibility of the Pope, divine right, the legitimacy of property, the happiness of the family and the harmony of the civilized world. – I am one of their number.

There are young folk everywhere from whom earthly angels avert their all-curing gaze. I swear by my life, such folk can endure everything, the very appearance of which throws the gracious young ladies into a tizzy and the later never have a kind word to spare them. – O, ladies, ladies, every evening you call blessings down upon your mothers, from whom you get your limpid eyes; and yet you cannot see past the attire of the very man who would love you best. – Again, I am one of their number.

Very well! I shall bear my loneliness. I will not squeeze my lungs into a corset just to escape it, and I will not deliver myself up as a willing victim into the hands of tailors and the tongues of drawing-room wits. I shall roll around this world like a stone tossed from the mountain top into the yawning chasm. The pine tree thrives only on arid summits; the eagle soars unattended into the sun. The sailor wrestles with the storm unaided; the emigrant forges on alone beneath strange skies. The huntsman in the hills lies in wait, alone, for the she-bear who has lost her cubs. The lion and the tiger prowl alone; the bull stands alone in the Spanish bullring. Everything strong has no need of support. – Quite the opposite .The frightened migratory birds huddle together in order to make headway against the wind; sheep need no encouragement to gather together; the ox stretches out his neck to the yoke; capons are held in cages, swine in the mud and princes in the palaces. Crows gather only over dead bodies and party followers only over a rioting populace.

Isn’t it at the mightiest oaks and tallest spires that the thunderstorm hurls its lightning bolts? Doesn’t the pack bay at the wild boar that stands up to it? Me against the world and the world against me: so be it! I accept the challenge and am proud to enter the fray alone, for I count it an honour not to be numbered among the common herd of my contemporaries. No one acknowledges me any more: those who used to call themselves my friends have shunned me. I haven’t a penny, not a single supporter, not a single mind well-disposed towards me; my attire does not fit me too well, my eyes are stung by the flickering of a 20 sou lamp on four white-washed walls.

What matter? My cause is a good one. I wage open war against the hypocrisy of the parties. Maybe I can force them at last to break with the conspiracy of silence and battery of calumnies they trot out every evening with their whispering campaign. For God’s sake, speak up and explain yourselves; set out whatever you will in the glare of publicity. I scream Thieves! because there are so many on every side, cowardly thieves that destroy a man’s reputation, tearing it to shreds, with the same carelessness with which a pick-pocket would shred a handkerchief.

I may not be famous, but, look, I should like you to tell the truth about me, and nothing but the truth, should you do me the honour of speaking about me. I am as hard to arm as any flint, but strike me with gusto and you’ll get your spark.

Only bites bring forth bleeding. The thunder is father to the lightning. Fire sucks at the wind. Do not attack the savage beast. Don’t pet the wolf. Don’t get in the way of a man striding towards his goal. Had I a spark of intelligence, some glimmer of embittered honesty, your Jesuitical attacks would alert me to it; they would suggest what I might do, what I should try; in the innermost recesses of my soul, they would strike the spark of revenge, the passage of which sets the blood coursing.

Partisan fury, I would give you my blessing! Stoke you wrath, parade your petty susceptibilities and sinister vengeance in battle array, hone your sneers, hurl your insults and, if you can, stretch to irony. If a man must go down fighting against the parties, I am willing to be that man, but I want to leave a fatal dart in their flanks. Until such time as I have no crust to chew on and no earth beneath my feet, I will cry out to men: Throw down the gauntlet to soldiers and Caesars, throw down the gauntlet to committed folk!

You who endowed the tiger with his fearful roar, the viper with its poison and its coils, Satan, God of vengeance, I turn to you. Make my tongue rough and my pen brutal and let my every utterance, like a two-edged sword, impale the slaves kneeling in the dust!

So that, when the day of reckoning comes I am entitled to cry: Freedom!

Let the stones pile up behind me, let the houses tremble and beasts of the forest prove as pitiless as men in the middle of burning villages.

And let Revolution enfold the globe in giant’s arm and squeeze until it bursts and gushes Eternal Fire over civilized folk!