In August 2014, two activists with the environmentalist group Rising Tide spent a week riding the backwoods highways of Idaho monitoring a megaload—a big rig hauling equipment for processing tar-sands oil that’s wide enough to take up two lanes of road, too high to fit under a freeway overpass, can be longer than a football field, and can weigh up to 1,000,000 pounds.

They had no idea that they would soon be wrapped up in a Federal Bureau of Investigation probe that encompassed three states and several environmentalist groups.

Helen Yost of Moscow, Idaho, and Herb Goodwin of Bellingham, Washington, have spent years travelling through area the bioregion of Cascadia to halt megaloads, from Washington and Oregon to Idaho and up through Montana. They are used to harassment from law enforcement. That week, Goodwin said, the two were stopped on average twice a night, by law-enforcement agencies ranging from state troopers to local police in Sandpoint and Moscow.

Usually carrying equipment to upgrade and expand tar sands mining in Alberta, Canada, megaloads make a torturous crawl along rural roads at night to avoid traffic, questions, and complaints. But activists like Goodwin and Yost have been remarkably successful at organizing the people in mountain country. In August 2013, more than a hundred people in Idaho participated in a four-day mobile blockade of a megaload on U.S. 12 headed for the Nez Perce reservation. The Nez Perce Nation said the megaloads threatened treaty-reserved resources, historic and cultural resources, and “tribal member health and welfare.” Tribal chair Silas Whitman was one of the blockaders arrested, while activists from Wild Idaho Rising Tide (WIRT), the group Yost helped form, played important support roles.

Rising Tide North America’s network, spun out of the Earth First! grass-roots environmentalist movement in 2005, now spans the Cascadia bioregion, with chapters in Seattle, Spokane, Olympia, Bellingham, and Vancouver, Washington; Portland, Oregon; Moscow, Idaho; Missoula, Montana; and Vancouver, B.C. In the last six months, they have collaborated on an average of a blockade per month, and have helped to spearhead the movement against fossil-fuel exports through the Pacific Northwest. The network has worked in solidarity with indigenous peoples to halt megaloads, has marched in pickets with unions to shut down ports, and has aided community groups to stop permits for coal, oil, and gas terminals on the Pacific Coast.

On Oct. 9, Herb Goodwin was approached at his home in Bellingham by two FBI agents asking about a group called Deep Green Resistance (DGR). The FBI and Joint Terrorism Taskforce had previously contacted several members of DGR and their families both by phone and through home visits in places as dispersed as Georgia, New York and Seattle.

Goodwin was alarmed but not surprised when the lead agent “flashed a badge and claimed to be from the FBI.” Refusing to tell him anything beyond her first name, “Brenda,” she provided a sloppy excuse for not presenting a business card [It has come to our attention that “Brenda” is likely Special Agent and FBI supervisor Brenda Wilson-Davis, who resides in Bellingham and is mentioned in the Rotary Club minutes as a counter-terrorism expert]. The other person identified himself as “Al Jensen,” and his card identified him as a member of the Criminal Intelligence Unit of the Bellingham Police Department.

“Jensen jocularly mentioned that we knew each other from the Occupy movement/camp and train blockade, attempting to coax up conversation,” Goodwin said in an e-mail. “I did not take the bait.”

The Occupy encampment in Bellingham lasted for two months in the winter of 2011-12. Goodwin was one of four people arrested during the eviction, which came about two weeks after the mass blockade of a coal train Jensen mentioned. He says he recognized the detective’s face, but didn’t know his name.

“I think he was one of the undercover guys who was shifting in and out of our camp for the couple of months we had the camp up,” Goodwin says. “I got a lot more surveillance after the Bellingham coal train blockade. I had people scoping out my apartment off and on for a couple months after that… I could see people scoping me from cars with binoculars.”

Goodwin says he is not a member of DGR, but suggests that it has drawn the interest of the FBI for advocating an “underground” strategy to dismantle industrial civilization. At the same time, he adds, “all the people remotely connected with DGR call themselves ‘aboveground,’ and they say that they’re going to be involved in the same kind of aboveground actions that other activist groups are, but as far as I know they haven’t really done anything.”

There is no love lost between DGR and Rising Tide. In February 2014, Rising Tide North America signed a letter along with some 40 other groups, such as Greenpeace, the National Lawyers Guild, and Tar Sands Blockade, petitioning the University of Oregon to cancel a keynote address by one of DGR’s leaders at an environmental-law conference on the grounds that the group’s transphobic beliefs promote “exclusionary hate that breeds an environment of hostility and violence.”

Questioning a Rising Tide activist about DGR seemed to blur some important differences between the groups, but activists still saw between the lines: The FBI inquisition was an obvious campaign to silence dissent. “When Herb got visited,” Yost says, “we knew it wouldn’t be long before they came around to someone from Idaho.”

Habeas Corpus Battle in Rural Idaho

On Oct. 9, the same day Goodwin was visited by the FBI, an activist named Alma Hasse attended a public meeting of the Payette County Planning and Zoning Commission to testify against the expansion of a gas-processing facility in the area, along the Oregon border northwest of Boise. She recommended that the five commission members recuse themselves from the permitting process on the grounds that they had signed oil and gas leases with Alta Mesa, the company seeking approval. (All three of the county commissioners have signed oil and gas leases as well.)

An associate of Yost and Goodwin, Hasse has worked in rural Idaho for years, agitating and organizing against fracking and oil trains. Cofounder of Idaho Residents Against Gas Extraction (IRAGE), which works with WIRT, she regularly attends Payette County government public meetings and brings up problems with their processes.

This time, something was different. The commission members closed the meeting to the public, brusquely challenging Hasse’s testimony, and ordering her to leave or face arrest. After insisting on her right to participate in the public meeting, she was arrested and kept in jail for a week without being charged or even processed.

In protest against her mistreatment by the commission, Hasse refused to give her name. Though the police knew her, and called her “Alma” when they talked about her, they refused her requests for a telephone call until she obtained a PIN number, which she could only get after being processed.

Police refused to process Hasse until she volunteered her name. Instead of booking her as “Jane Doe” (a formality, since they already knew her name), they kept her in a cell by herself.

“I felt like it was a game,” Hasse says. “They had my name. I had to sign in to testify at the public hearing, so both my name and my address were on the sign-in sheet.” She also had been granted a permit to carry a concealed weapon by the county sheriff’s office, so they had her Social Security number, date of birth, and fingerprints.

When police asked for her name, Hasse would tell them that they already knew her name, and that she wanted to talk to her attorney. They refused, which she insists was a violation of her civil rights and right of habeas corpus.

Only after she drew attention to her incarceration by going on a hunger strike, supported by a media campaign led by her husband and civil disobedience spearheaded by her daughter and WIRT, was she allowed to go free.

“I felt like I had to stand on principle,” Hasse says. “At some point, we as citizens have to stand up and assert our rights, because if we don’t, we’re just going to be steamrolled.”

When the FBI Sends Texts

On Dec. 10, Helen Yost of WIRT received three phone calls from an unfamiliar number in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. Thinking they were from a telemarketer, she did not answer them. But nine days later, she awoke to another call from the same number. She had anticipated the text message that followed for years.

“Helen, I am trying to get a hold of you to speak with you. An issue has come up, and I need to speak with you. Please give me a call. I am an FBI agent. SA Travis Thiede.”

Yost responded within ten minutes: “NO!”

Agent Thiede’s reply came four minutes later: “OK, I understand, just wanted to have a conversation with you. Thanks.”

According to his LinkedIn profile, Thiede joined the FBI in 1997 after serving in the Army and as a police officer in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He was involved in the providing security at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City and the investigation of a power-station bombing on the games’ last day.

Yost believes that the agent’s calls were related to her role as an organizer with WIRT. On Dec. 10, the day the first ones were placed, she had just returned to Moscow from a road trip organizing for the third annual Stand Up! Fight Back! Against Fossil Fuels in the Northwest! She’d been in Sandpoint on Dec. 8 and in Spokane, about 35 miles from the FBI office in Coeur d’Alene, on Dec. 9.

Continuing Harassment

After years of dedicated activism, Hasse and Yost were not surprised. Groups like IRAGE and Rising Tide have felt the presence of the FBI for years.

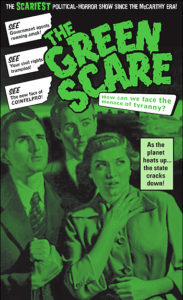

The intensity of repression depends on the success of their campaigns, and not since the late 1990s has the Pacific Northwest seen so much mass action for environmental causes. During that period, the FBI inaugurated a broad strategy of repression, known by activists as the Green Scare, to track down suspects implicated in actions deemed “eco-terrorist.”

According to leaked documents, its surveillance net was so large that officers even tailed random Subaru-driving patrons of a farmers’ market. Earth Liberation Front spokesperson Craig Rosebraughwas subpoenaed eight times to testify before grand juries. The FBI’s Operation Backfire led to 13 people being indicted and nine convicted on various charges, including arson. Of the other four, one committed suicide in jail, two are still fugitives, and one escaped prison time by turning snitch, but was later jailed on heroin charges.

That era is said to have ended in 2006, but the bureau is still using agent provocateurs to infiltrate environmental and social-justice movements. (One was recently arrested for failing to register as a sex offender and for credit-card fraud.) In 2008, a young man named Eric McDavid was sentenced to more than 19 years in prison, after an agent provocateur who called herself “Anna” seduced him into talking about committing acts of sabotage at a cabin in Northern California the FBI had rented and wired for her.

Legislation such as the 2006 federal Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, largely drafted by the far-right corporate American Legislative Exchange Council, has expanded the criminalization of advocacy for the environment and animal rights. Because of Idaho’s new “ag-gag” law—enacted in February after animal-rights activists released videos of dairy workers abusing cows, it outlaws filming or recording agricultural operations without permission—activists in Payette County are afraid to take photographs of new fossil fuel wells and processing plants.

The surveillance has continued apace, as well. In 2011, activists with WIRT heard from an arrested megaload blockader that the local police were communicating with the FBI. They wrangled two meetings with the police and sheriff, but did not get any substantial information regarding the extent of federal involvement.

That fall, minutes after Yost received a call from an activist telling her that a protest was about to begin, police showed up and shined flashlights into people’s cars. She believes they learned the protest’s location by tapping her phone. The local sheriff also approached associates of a professor at a university in Spokane and asked them about why he “liked” WIRT’s Facebook page.

In June 2013, the FBI called the parents of an activist with Portland Rising Tide, and six other activists who have worked with Rising Tide Seattle were visited by FBI terrorism expert Matthew Acker and forensics leader Kera O’Reilly. There was also a third agent, who did not give his information.

The agents asked about the movement against tar-sands and fossil-fuel shipments. It was apparent immediately that the target was the Summer Heat action scheduled for that July 27, a joint effort with 350.org that would send a hundred or more kayaks and boats into the Columbia River for a symbolic blockade on to protest coal barges, oil-by-rail, and gas pipelines.

“My [attorney] was not able to find out what or why they were bothering my sweet folks, but I will tell you why,” one activist whose parents were visited wrote. “Its [sic] because Portland Rising Tide is outreaching, training, and organizing hundreds of Pacific NWers of all age groups to engage in a level of civil disobedience not seen in decades. We are going to do it to save our neighborhoods, our communities, our salmon, and our climate. And that scares the shit out of the powers that be.”

This article originally appeared at DefendingDissent.org

Alexander Reid Ross is a contributing moderator of the Earth First! Newswire and works for Bark. He is the editor of Grabbing Back: Essays Against the Global Land Grab (AK Press 2014) and a contributor to Life During Wartime (AK Press 2013). This article is also being published at CounterPunch.

by Alexander Reid Ross / Defending Dissent