This collection of articles, published during August 1918 in the newspaper of the PPS-Left, while clearly supportive of the Bolsheviks, discusses many controversial aspects of their rule: the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the peasantry, the terror, as well as the question of democracy. Koszutska encourages the international proletariat to take an active part in the events, and help guide them on the correct path to socialism, rather than remain critics on the outside.

I. UNITY OF PROLETARIAN STRUGGLE

The east or west of Europe? Russia, swelled by the winds of a raging social storm, seemingly not aware of any boundaries in its revolutionary impetus, albeit immature in its capitalist development, Russia, moving directly from despotism and a half-feudal apparatus to bold attempts at realising socialism, or the level-headed West, with its old practices of social organisation, far reaching economic development, and the huge resources of theoretical knowledge and understanding of the workings of social life at the hands of its socialist advocates? The exuberant power of Russian worker-peasant masses pressing forward, most of which, grown upon still underdeveloped economic relations, nevertheless have absorbed the elements of an international revolution in the making, and adjusted their demands and aims to an international scale – will these masses, only just broken from the shackles of a most severe enslavement, ultimately decide on the new forms of social-economic life, or will the training and organisational skills of the west European proletariat show its superiority after all? Who will get the last word in the historical contest between battling classes, in the enormous struggle of hostile forces? Who will steal from the heavens the promethean fire of human happiness? Does the key to solving the great matter of our present epoch lie in the east or west of Europe?

It is in vain to look for answers to questions posed this way. The countries of capitalist Europe are linked to each other by a chain of unbroken connection, interaction and dependency; that which happens in one of them cannot remain with no effect on the formation and system of general relations; no fundamental social-economic revolution can happen and be maintained in only one country. In this unit there can be no isolated island of happiness, nor can there be a fortress of backwardness and enslavement which could not be abolished by a general wave of liberty. There can be no national socialism, no national liberty secure from general reaction, no chosen nation called up to the salvation of others – all of them having passed together, some at a slower others at a faster pace, the process of transformation to a capitalist society, together too will transform into a socialist society.

The character of the current revolution in Russia is already the result of not only a concrete system of relations in Russia itself, but also to a large degree conditioned by the maturity of social construction in western Europe, it is in a way an investment on the future legacy of the international proletariat, it is a way out of the national framework for the revolution and the relocation of the struggle onto a European wide terrain. And at the same time, the Russian revolution, its results, achievements and at times the heavy price paid for its experiences will not only be a material for observation and the drawing of historical lessons for the proletariat throughout the rest of Europe, but will also serve as the most important constituent part of the overall transformation.

Therefore, being exactly aware of the differences in the system of relations between the West and the East, knowing that history never repeats itself in such a way as to bring together a complete similarity of events once lived – understanding it all, we are still confident that the Russian events cannot remain isolated.

This point of view serves as an indication on the need to establish our relation to the Bolsheviks as to a revolutionary workers’ government.

II. THE BOLSHEVIKS AND US

The differences separating us from the Bolsheviks are the differences between various factions within the socialist camp. The link connecting us with them, placed above all – the common interest of the proletariat. Support and maintenance of the workers’ government – that is the first task, the duty of the international proletariat. Criticism of it cannot be that of outside observers, but comrades attempting to rectify mistakes that the proletariat could never shake off if it saw the leadership as an infallible deity.

It is impossible to conceal that the stages of the Russian Revolution are often incomprehensible, that they often bring disappointment to the masses which greeted the revolution with the highest exultation, and which later began to lose orientation in the jungle of unsolved multiplying problems.

The defeat of Russia sealed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the terrible conditions of the treaty, the inconceivable fact of a covenant between a bourgeois government and a revolutionary government – this is one kind of doubt.

But that is not everything. The abuse of the principles of democratism, which, during the long years of struggle, have become a beloved symbol of freedom and justice for the masses. The reign of violence, terror and turmoil in a socialist state, where the ideal of harmonious coexistence of all peoples was supposed to be realised! The worker’s mind is lost in these contradictions … And finally – the chaos and economic disorder, speculation, high prices, lack of jobs – as a result of socialist governance… The fragmentation of land instead of socialisation, hunger and poverty in the cities instead of expected prosperity…

Is there no way to rise from these lowly plains, which fate has pushed us into? Will socialism then, which so far has been our guiding star, not stand the test of life and in practice turn out to be an unrealisable dream? Are we to doubt ourselves? – because why, having power in their hands and the ability to organize life according to their will, workers cannot organise it properly? Or perhaps it is all the fault of Bolshevism and its mistakes, as it has been attempted to prove to us hundreds of times?

The hope of the coming great days of liberation and self-doubt; a sense of unity with the workers’ government and a concern about the validity of its tactics; these feelings are still fighting each other for the hearts and minds of the workers.

The answers we must seek, as always, on the roads of socialist consciousness. The one who understands the routes and impulses of the Russian Revolution, the thrust that it receives from the overall maturity of capitalism in Europe, and the constraints in which it is entangled by the underdevelopment of Russia; who looks at the whole terrible legacy of the war and of the tsarist rule that the socialist government inherited, who understands the difficulties with which it fights – will inevitably cease to grieve and recklessly accuse. In all this, which on the surface appears to be only chaos, one will see the action of creative forces, will know how deep the roots of the evil troubling the proletariat lie, as will they know the titanic efforts of those who try to break these evils and the dangers that threaten them on the way.

They will know their mistakes and learn how to avoid them.

In Russia – where the masses, generally in the dark and for many years passive, only just came out of enslavement – there was a lack of organisational democratism in its socialist parties, and the dictatorial aspirations of individuals grew to unbearable limits. The circles of exclusivity and organisational despotism were often the cause for lack of restraint in the measures undertaken in the struggle for power. This led to demagoguery and opportunism towards non-proletarian peasant fervours. Finally – a tendency to rely on tactics not only based on an understanding of the general pattern of social development, but also on reckless prophecies about the timing and speed of revolutionary events, a characteristic specific to the Bolsheviks – and over here [in Poland], with some variations, to Social Democratic splits. In the course of the revolution, this tendency has clearly shown its harmfulness to the labour movement, and has to be, in spite of all that connects it most closely with Bolshevism, ruthlessly countered and suppressed by the international proletariat.

Our comrades in Russia have similarly understood their relationship to the Bolshevik government and in the Petersburg “Robotnik” characterized it in the following words:

The ranks of the Polish proletariat taken by the winds of the war to Russia, the proletariat of the country where the revolution of 1905 and 1906 took the course of a purely working class revolution, these ranks were confused and disconcerted with the course taken by the Russian Revolution.

However, no faction of the Polish working class can limit their activities to criticism from the outside.

Collaborating as far as possible and fighting alongside the workers’ government – the “Robotnik” continues – we must at the same time be cautious of completely dissolving in the, mixed in terms of class elements, revolutionary fervour, and must bitterly guard and defend the unbroken principles of workers’ Marxian socialism; even among the revolutionary struggle we have to protect the class independence of the proletariat, which has its own historic task to complete.

The huge efforts and heroic sacrifices of the Russian proletariat would be largely wasted if they did not find support and were not sustained by the international proletariat, and if on the other side they did not help to avoid these mistakes and these dangers which the Russian Revolution and its leadership failed to avoid.

III. DICTATORSHIP OF THE RUSSIAN PROLETARIAT AND THE BREST-LITOVSK TREATY

Was the October Revolution and the seizing of power by the socialist proletariat of Russia not a capital mistake, giving birth to a series of further errors? Should socialists realise the slogan of dictatorship when capitalist development is not yet ripe for socialism, and when socialist rule, exercised on the basis of still existing capitalism, is at every step compelled to make compromises? And even if we give an affirmative answer to this question, should we take responsibility for settling a losing war? Should the Russian socialists have stood at the head of a government when they had before them only two alternatives, equally unacceptable for them: bargaining with imperialism, or the continuation of the war? Here is the paramount issue of the Russian Revolution, which requires an unambiguous answer. It has to be said that, after all, this historic attempt and responsibility could not be rejected.

To say that the dictatorship of the Russian proletariat should have been realized only when capitalist development reached its maximum, trying to get around the dangers of transition in this way – it would mean to imagine that socialism can with time, like a juicy fruit, ripen on the tree of capitalism and fall into the hands of the proletariat as something ready and finished, it would mean to believe in the possibility of a one-time instantaneous revolution and not comprehend the necessity of attaining socialism by a struggle against the capitalist world.

It would also be illusory to assume that the attainment of the dictatorship of the proletariat should be left for such a favourable moment when socialist power will immediately be able to deliver heaven on earth, provide freedom, prosperity and happiness for everyone. Those who would have waited for such a moment in Russia, might not have gotten it at all, because that is the normal order of things, that the way to power and victory over the enemy classes opens for the proletariat when the policies of the enemy class, having brought about some kind of total disaster, weakens them and arms the broad masses, torn out of their usual apathy.

At that moment the proletariat could not just say to the bourgeoisie: I do not want power, I do not want to drink the beer brewed by you, but because you sinned hard, I will force you to repent and to rule in my interest, not yours. Demanding from the bourgeoisie such a, even if temporary, self-restraint would be futile, as leaving power in the hands of the bourgeoisie, the proletariat would be preparing a further whipping of its own. Not only reasoning, but also the instincts of self-defence do not allow for it, and at such a moment push workers to become the guardians of their own interests, irrespective of the difficulty of the situation. Gaining power is not, and cannot be, a miracle cure, revoking all the evil caused by the previous economy, but it does put an end to policies which bring ever new disasters and is moreover a way towards great achievements on the field of awareness and training of the masses.

The understanding and accurate assessment of this situation is absolutely a great merit of the Bolsheviks. “Robotnik w Rosji”, the organ of the PPS-Left, also states that:

The historic mistake of Menshevism was that, based on an analysis of European rather than Russian relations, it saw in the dictatorship only one of the possibilities of the spontaneous development of the revolution, and in fear of this false conception, in which the proletariat will find itself if it obtains power at a moment still immature for the socialist revolution, it hesitated to take the lead of the movement, which through spontaneous developments did push towards dictatorship.

But they also say that: due to the weakness and small size of the proletariat, which in these conditions could not realise its own aims, it should not have seized power at the cost of distribution of land and a “muzhik” peace, it should not have become a tool in this way, giving socialism over to the non-socialist aspirations of the peasantry.

And that is wrong. For if the land and the peace was indeed the price paid for peasants to put power in the hands of the socialists, then it was ransom to which the socialists could and had the right to agree to.

Fragmentation of land is not socialism of course, and it seemingly takes us further away from it, as a step back from the process of concentration of capital. But the destruction of landlordism, this refuge of reaction in Russia, was a historic necessity and a condition for further development, and the distribution of land was not only the price paid for socialist power, but the price of the revolution itself. And, after all, the struggle for peace, since the beginning of the war, belonged to the sphere of socialist agitation.

It is not so much the seizure of power that can be the subject of our criticism then, but how it is used and taken advantage of.

We do not accuse the Bolsheviks of agreeing to govern a country in which the peasantry constituted the majority, but that, relying on the strength of the armed peasantry, they did not clearly see the potential dangers involved and made terror and violence their system of governance not only in relation to the bourgeoisie, but also often in places where only ideological force should have been victorious.

We do not see the evil in that directly or indirectly they helped the fragmentation of land, but in the fact that they had not seen and did not understand the essence of the agricultural revolution taking place, which they considered to be a socialist revolution.

We should not blame the Bolsheviks that they have become the reason for the triumph of the Central Powers. Even before seizing power, Russia was utterly beaten, and no human influence could restore its fighting strength. At that moment, the triumphant Central Powers had their way open to Russia – it was only a question of in what form the triumph would find its expression. But it was extremely important that in the only country where the socialist proletariat could lead to the end of the war – that this fact could find reasonable protection.

It should have been said clearly that in such a situation a momentary armed triumph of these powers, in which the proletariat still supported the military action of the bourgeoisie, was possible, but that this should not be the motive to abandon the anti-war course. After all, all conciliatory socialists agree to lay down their arms, but only if the proletariat on the opposite side does so too – the question of revolution comes down to who will make the first move, who will take the great risk of exposure to the lack of immediate support, to who will burst out of the cursed circle of short-sighted calculation and back in practice, not just in theory, the general prospect of the progressing forward advance of the class struggle.

That is what the Bolsheviks did not explain, did not even try to explain to the masses – and they tied all their hopes not with the general course of revolutionary events in Europe, but with their own providential role, the role of miracle makers, able to bring forth an international revolution at a time decided by them – when negotiations at Brest-Litovsk were happening.

The measure of disappointment after the conclusion of Brest-Litovsk was so great, it overcame not only the broad masses, who always judge events by their direct consequences, but also conscious worker circles, lacking at this defining moment the ideological weapon. For this weapons could not be provided by the vague slogan of revolutionary war, nor the visibly misleading, due to its unenforceability, Leninist theory of “peredyshka” – a breathing space, only to be followed by renewal of the war – a theory being a clear concession to the ideology of national defence.

Without going into the matters of form, in which the withdrawal of Russia from its active role in the European war took place, absolutely rejecting all accusations that the Bolsheviks were the cause behind enhancing the powers of one of the imperialist groups or “humiliating” Russia, we conclude that this withdrawal from the war, in the awareness of the many – to a large extent thanks to the tactics of the Bolsheviks – was only a triumph of the facts, a “muzhik” peace of ignorance and exhaustion, rather than an expression of revolutionary aspirations irreconcilable with war and anti-war socialist ideology.

IV. DICTATORSHIP OF THE RUSSIAN PROLETARIAT AND DEMOCRACY

The bourgeois press competes with each other in their attempts to denounce the Russian workers’ government. Both the general system and its activities, as well as specific regulations and decrees, and so the fact of the dispersion of the Constituent Assembly, the content of the recently announced constitutional text, etc. are considered to be irrefutable proof that the socialists have betrayed their slogans of freedom, justice, equality, that they perverted the ideals of democracy, i.e. aspirations to universal equal rights, and that in the place of Tsarist despotism they introduced socialist-Bolshevik despotism. This incessant barking of the bourgeois press, with the simultaneous intricacies of events occurring in Russia and new issues arising out of the seizure of power by the proletariat – all evoke in the minds of many workers serious doubts as to whether and to what extent the political practice of the proletarian government in Russia is consistent with the ultimate objective of this struggle, with the ideals of socialism. For the working class socialism is after all synonymous with the reign of universal equality and justice, it is the ideal of brotherhood and of free unfettered development of all members of society. Meanwhile, the first case of sustained proletarian power has already significantly abounded in acts of violence, giving a whole set of examples of coercion and discrimination between members of society. This raises an additional question, is coercion in the era of the reign of the proletariat consistent with the libertarian ideals of socialism? A number of issues interlace here which require separate consideration.

The hastiness of the Bolshevik government in the use of force, especially when it concerned different factions of the working class and where violence replaced ideological disputes – was undoubtedly a mistake to which we will return. For now, however, we are concerned with a more general approach to the problem – to answer the question, what measures can be applied in general, not only within their own class, by the victorious proletariat. We need to discuss the very concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat. What is a dictatorship and what should be its content?

Socialist theory does not give a ready answer here. Although in the works of the authors of scientific socialism, Marx and Engels and subsequent socialist theorists, there are rare comments which could allow for a more concrete grasp of the methods of proletarian politics in the era of its reign, until the recent period, the issue was not urgent enough and so comments remained generalisations. This in turn gave birth to and strengthened the widespread belief that the capture of state power by the proletariat entails almost directly socialism, and therefore the realisation of all of its ideals and the grounding of human relations on the principles of peaceful coexistence. However, the more we approach the period of critical social struggles, the more accurately we realise that this is not the case, that the realisation of socialism and creation of a new system of human coexistence cannot be the work of a moment. Socialism will not be born overnight. Building the new social order must fulfil the entire period of heavy struggles of the proletariat. The duration of this depends on many factors – the strength and maturity of the proletariat, on the resistance of the enemies of socialism. Socialist revolution then is not a single action, but a series of battles that fill the entire period in the history of society.

And that is why, taking power into its hands, the Russian proletariat could not immediately destroy the state organisation as an instrument of domination by one class over another. It would deprive itself of the most important tool for the creation of the socialist system, which can only arise through enforcement by means of coercion – the will of the working class against other classes. In the social struggle it is not persuasion of opponents of the class that will settle the matter but power – in this case the power of an organised, conscious of its objectives ruling proletariat. Resistance of social opponents must be broken, if other measures are not effective. That is what the bourgeois revolutions also teach us, e.g. the English in the mid-seventeenth century and the French in the late eighteenth century, when the bourgeois elements used all means in order to consolidate their power and did not heed any grievances or accusations by the former rulers of the middle-age-feudal world.

Regardless of whether we consider the Russian dictatorship as a temporary victory, or as a final transitional period from capitalism to socialism – in any case, the proletariat, which becomes the ruling class through the revolution, must, as the ruling class, seek to overturn the existing economic and political system. This starts the extremely cumbersome and complicated task to reform the entire social-economic mechanism, with the socialisation of the system of production as its purpose. It is therefore necessary to remodel the whole state apparatus, to destroy the organs of the state as a tool of class oppression, and build a political mechanism that allows for a great social reform. All this is being done by the Russian proletariat, against the will of bourgeoisie, with fierce resistance and many obstacles posed, a bourgeoisie which does not want to voluntarily get rid of its privileged position.

Therefore, this period of the dictatorship of the proletariat is not, as some people think, the organisation of life on the principles of universal harmony and agreement, but it is, on the contrary, the duration of the most fierce war between classes, each of which wants to forcibly carry out its aspirations.

Any idyllic ideas of dictatorship are an illusion and must be dispelled by reality. This reality can easily bring disappointment to many, even sincere idealists, who see socialism only in the lofty slogans of brotherhood and equality of all people, but do not see the, admittedly transitional, but hard and cruel requirements of the struggle. However, if one does not want to be pushed out of the great road of struggle for a better future, they must investigate matters deeply and understand the content and nature of the revolutions taking place, not just its external, accompanying symptoms.

Efforts of the Russian proletariat are based on a “revolution in the old system of production”. At the point when the proletariat “sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class.” The period of the dictatorship of the proletariat will be over, because, with new social-economic conditions, the working class – whose product of labour is usurped by the bourgeoisie, which owns the means and instruments of production – ceases to exist. These means will become the property of the whole of Russian society. When the bourgeoisie disappears, so does the proletariat. The rule of the proletariat loses its social foundation and becomes unnecessary.

Along with the end of the period of transition from capitalism to socialism, a new era in the history of Russia will begin – the epoch of socialism, justice in relation to each individual, freedom and equal rights and obligations for all members of the new society.

All that we have said about the need for compulsion in the era of the dictatorship of the proletariat still does not explain the issue of the relation of the proletariat to the ideals of democracy. Because it is not only about how to fight and by what means, but also about the very objective, it is about the question of what are to be the new instruments, new forms introduced in place of those that are broken by force and destroyed.

Democracy, and universal equal rights as its expression – equal right of all citizens to participate in political life, respect for the will of the representation of the population and support of the basis of that representation on the broadest foundations, the abolition of all privileges in the sense of any legal advantage of some citizens over others – these were, after all, demands which are a component part of the socialist programme. We had it stored in memory – we, the socialists, we learned it as children learn prayers. In every worker’s circle we discussed the details of this programme, we got to know the ways in which to implement it and protect it against any violations.

And behold, when the socialists came to power, in one fell swoop they nullified the democratic programme: armed sailors dispersed the Constituent Assembly, one that was chosen on the basis of the broadest possible right to vote, and the Fifth All-Russian Congress of Soviets passed a constitution, in which universal suffrage has been repealed. A paragraph of the first constitution proclaims:

The following persons enjoy neither the right to vote nor the right to be voted for:

(a) Persons who employ hired labour in order to obtain from it an increase in profits;

(b) Persons who have an income without doing any work, such as interest from capital, receipts from property, etc.

The bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie then are removed from the voting process.

And where is the democratic programme – may ask the Russian workers – where are our demands, for which we have fought for so many years and shed blood, where are the slogans of the 1905 Revolution – a constituent assembly and universal suffrage?

Where are your principles, your ideals? – Cries out the bourgeoisie with rage and triumph. – So civic equality was only necessary for you when you were the weaker side; as soon as you come to power, you use it in order to suppress others; having broken your own tether, you impose it on your neighbour… Do not tell us about socialist ideals, your ideal – is the rule of the fist, the only difference being that it should be a worker’s fist, and not that of the bourgeoisie!

From the Kraków “Czas”, through the Warsaw “Dwugroszówka” and “Głos”, ending with the quasi-socialist “Jedność Robotnicza” – everywhere the same: spewing venom and bile, mockery, ridicule, indignation, and in the best case, grief and regrets. The very titles of these articles, namely: Caricature Constitution, Bolshevik Anti-constitution, etc. speak clearly about the content. “Jedność Robotnicza” is tearing its clothes proving that a workers’ government betrayed the most basic socialist principle: striving to overthrow all privilege, as itself it privileges the workers, basing the new constitution on privilege.

So at every step the enemies and uncalled for friends of the working class of Russia are trying to impose on it dead projects, dry formulation to replace the living fabric of life and struggle.

Socialists were always different in this from the bourgeois-democrats, that no mechanism of political life has ever been an ideal for them – it was always only a means, a tool in the battle to obtain the essential ideal, the abolition of exploitation and of all social privileges. If this tool, one or other form of political life, hinders the whole struggle for liberation, it is to be rejected without the slightest adverse effect on the ideal. If democratic devices, if equality of political rights, which in essence is a fiction, because a capitalist with education and money has other uses of their electoral rights than the hungry worker in the dark who often turns this right against themselves – if this apparent equality is to prevent the burying of the main sources of social inequality of people – it cannot be an untouchable sanctity for us. And that is why if the same principle, in certain exceptional cases, means the transitional period does not take into account the demands of a democratic program, it is correct.

When it came to the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, the question of a Bolshevik majority was not the only issue. And even if the immediate motive for the proceedings of the Bolsheviks was that they did not obtain the majority in the Constituent Assembly, which they did have among the people, there entered into play yet another factor. Here, in front of the Constituent Assembly, a different form of people’s power was created, better suited to the needs of the moment and for drawing the toiling masses into an active role in public life; these were the soviets. Constituent Assembly or soviets – that was the question. There had to be a decision. The one and the other could not coexist; one or the other had to become a fiction or cease to exist.

But then why would the Bolsheviks call for a constituent assembly in the first place, if they knew that it was doomed? Why did they give their opponents all over the world as easy an ideological weapon in hand? Why did they not prepare minds, did they not reckon with the disastrous impression that a sudden disregard for traditional democracy would have on the workers of the West, accustomed to existing forms of struggle and rotating in a conceptual circle of the current democratic program?

Yes, without a doubt, the call for a constituent assembly was a mistake, but this mistake was probably unavoidable. Because it was a slogan which inevitably arose as it were in the fight against the dictatorship of Kerensky, a slogan, which broadcasted the content of political agitation against him. The new form of political organisation, soviet power, crystallised only in the heat of battle and its rise in place of the old forms of parliamentarism was not the result of theory, but the work of practice – almost a surprise to the creators of the new organisation.

The new form of people’s power born in Russia, formed in the heat of the revolutionary struggle, finds its expression, defence and ideological justification in the text of the Constitution passed by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets. The state mechanism established by the Constitution, its kind of legislative and administrative bodies, their mutual relations, etc. correspond closely to the design that emerged spontaneously out of the soviet organisation and the earlier ways that stood the test of time of the proletariat organised in socialist political organisations.

In place of former party committees, we now see the council, or local soviets, from whose delegates county [uyezd], municipal, governorate [guberniya] and provincial [oblast] soviets are formed, and finally the highest body: the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which selects the Executive [VTsIK], and this further elects the People’s Commissars [Sovnarkom]. Commissars are subject to constant control of the Executive and each of their decrees may be suspended and put on the agenda of the Congress of the Soviets.

Within their jurisdiction, the local, municipal, governorate and provincial executives constitute the supreme authority.

Elections in all soviets are held every three months, through which constant communication and collaboration is maintained between delegates and the voters.

The new organisation of people’s power resolves in one fell swoop the issues that have long been of concern to the socialist camp and caused doubt as to the advisability of participation in parliamentary life. The current parliamentary system does not allow the masses to actively participate in public life. The administrative body, disconnected completely from the general population, from legislative bodies – ossified in dead bureaucratism, becomes a foreign, hostile, parasitic growth in the womb of society. Finally, empowered by the masses, ministers drift apart from them, and stop participating in the life of the masses – the masses stop cooperating with them.

All these deficiencies are removed by the new state organisation that connects all cells of social life into a whole, removes older artificial divisions, makes local government bodies a component part of the overall state organism, establishes a close link between legislative and administrative authorities, introduces the principle of frequent elections, etc.

The Constitution of the Russian Republic is the first major attempt to organise the life of the working population on the basis of real self-government, that is governing yourself, rather than being subject to a power enforced from above.

As for depriving the bourgeoisie of electoral rights, this step can be explained in different ways.

If we treat the current dictatorship of the Russian proletariat as a momentary victory, the needs of the struggle of this decisive period are the justification. In the transitional period of this deadly contest against reaction the proletariat has to act with feverish haste and straightforwardness. The people’s government must act, decide and perform – it cannot waste time on fruitless discussions with their class enemies, it cannot afford to poison the revolutionary atmosphere by bribery and all the machinations of the bourgeoisie, which, if allowed to participate in representative bodies, would paralyse all their activities. And if the dictatorship of the proletariat is the immediate preparation preceding the establishment of socialism, depriving the bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie of voting rights would also signal the beginning of a new era in the life of a society based solely on the principles of labour.

The backwardness of today’s social structure in Russia, the undergoing class differentiation and division into numerous factions of vaguely delineated class interests and a fuzzy physiognomy of the class – means that carrying out in practice the removal of petty bourgeoisie voting rights to the full extent, would inevitably prove to be unfeasible, and the meaning of the policy is rather a principle for the future – the principle of labour as a condition of acceptance of the individual into the community.

Originally published in “Głos Robotniczy”, no. 55-57, 59 (170-172, 174), August 1918. This translation is based on Maria Koszutska (Wera-Kostrzewa), ‘Rewolucja rosyjska a proletariat międzynarodowy’, Pisma i przemówienia, Vol. I (Książka i Wiedza, 1961), p. 237-255.

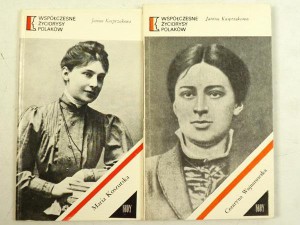

Maria Koszutska (pseudonym Wera Kostrzewa, 1876-1939) was a participant of the 1905 Revolution, a member of the PPS-Left, as well as leader and founding member of the Communist Workers Party of Poland (in 1925 renamed the Communist Party of Poland). An opponent of Stalinism, Koszutska was arrested in the purges of 1937 and perished in a prison.